For Trump, Michael Jordan and the Jumpman are now gang symbols Another absurd story involving the President of the United States

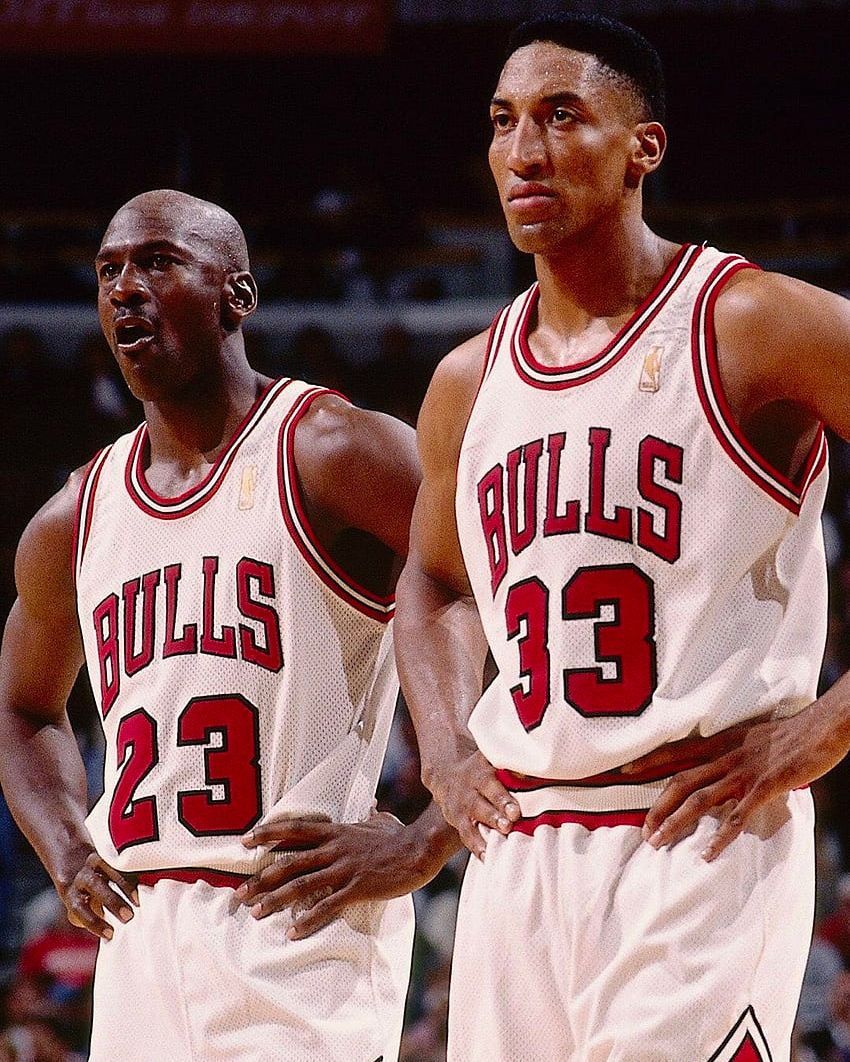

In the United States in 2025, sporting a tattoo featuring the silhouette of Michael Jordan, a pair of his iconic shoes, or a number 23 jersey from the Chicago Bulls could potentially be interpreted as a sign of affiliation to Tren de Aragua gang. These elements have been highlighted in Exhibit 2, a contentious document recently released by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which identifies the Jordan and Bulls logos as possible indicators of ties to the Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan criminal organization deemed by many as "the world's most dangerous gang," a characterization notably used by President Donald Trump.

Described by former Colombian Vice President Oscar Naranjo as “Latin America’s most destabilizing organization,” the Tren de Aragua emerged in northern Venezuela at the dawn of the new millennium. The group quickly evolved into a transnational entity, notorious for engaging in typical ‘parastatal’ crimes including violence, kidnappings, extortion, and trafficking in drugs, arms, and humans. By 2024, the gang had grown to encompass over 5,000 members and boasted an annual revenue exceeding $15 million. The surge in regional migration has facilitated the establishment of their first bases in the United States, leading to violent incidents reported in cities such as Chicago, New York, Salt Lake City, and beyond.

It's hardly surprising that by 2025, Donald Trump emerged as the organisation's biggest enemy. In March of that year, the Republican leader officially designated the group as a foreign terrorist organization, equating it with MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and Mexican drug trafficking cartels. This classification served as a foundation for Trump's familiar anti-immigration rhetoric, leading to severe measures such as the expulsion and deportation of Venezuelan citizens. These actions have drawn widespread condemnation across the globe, not only due to the questionable legality of forced deportations but also because of the ambiguous standards used to label individuals as (alleged) criminals.

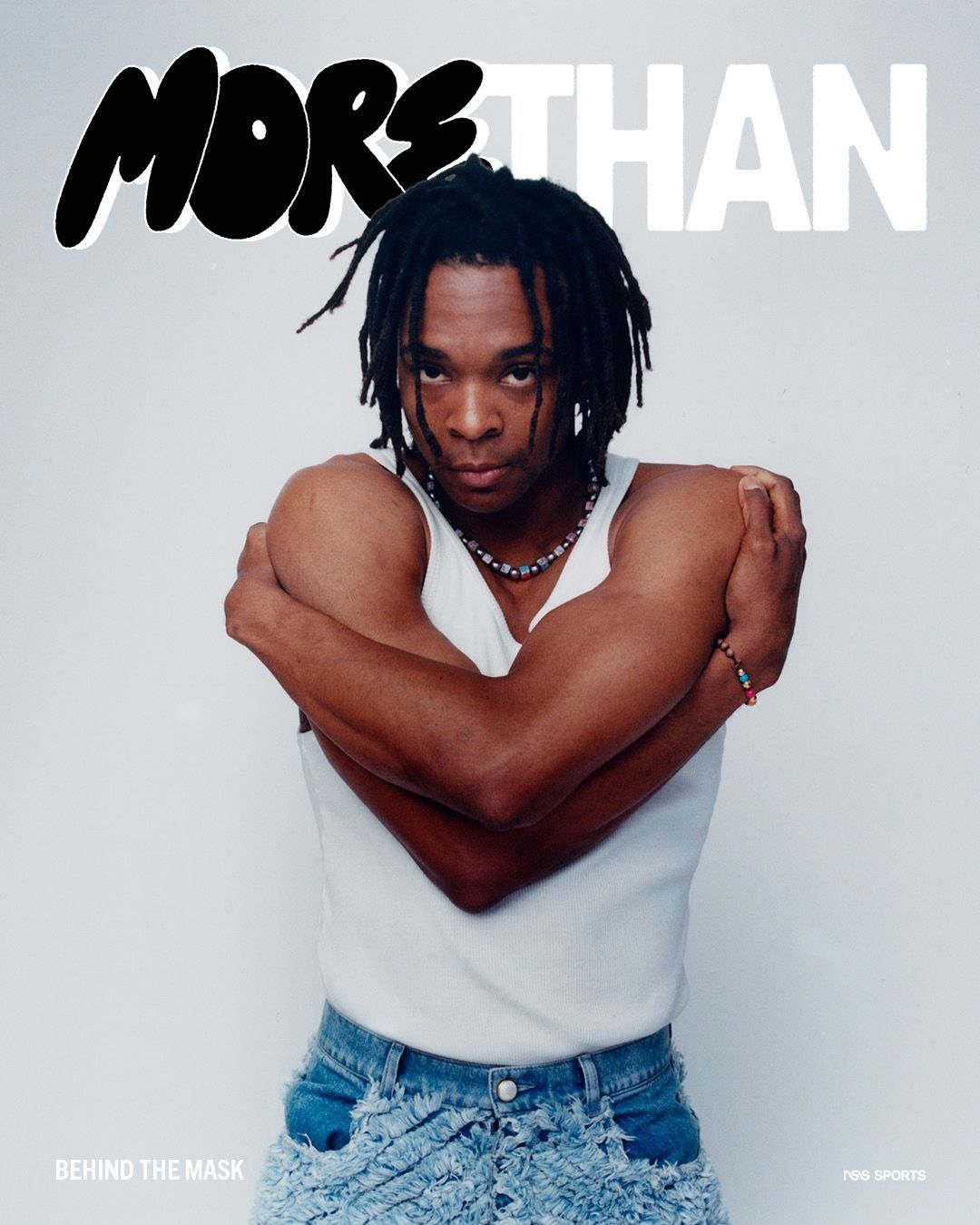

‘Jumpman' and other clues

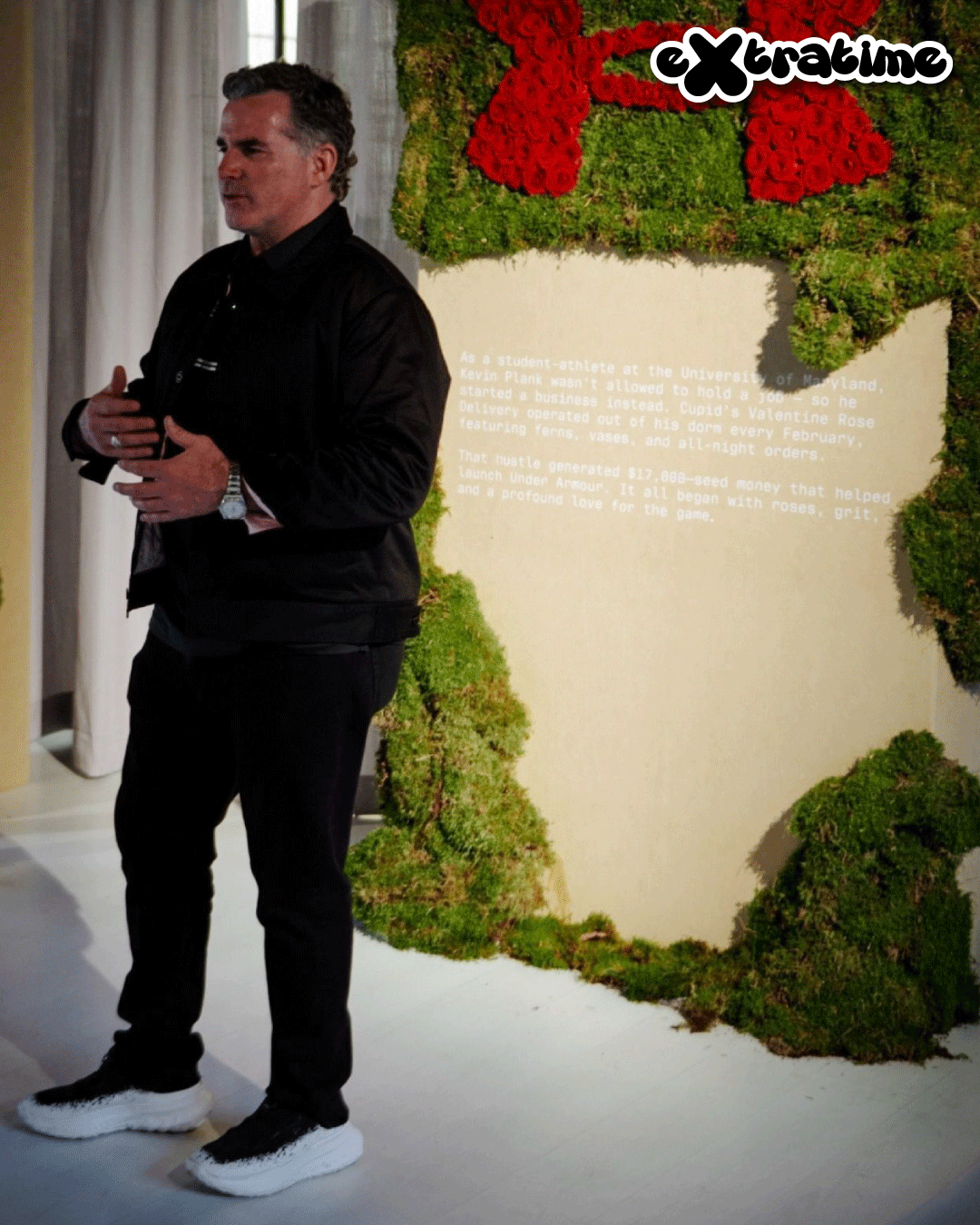

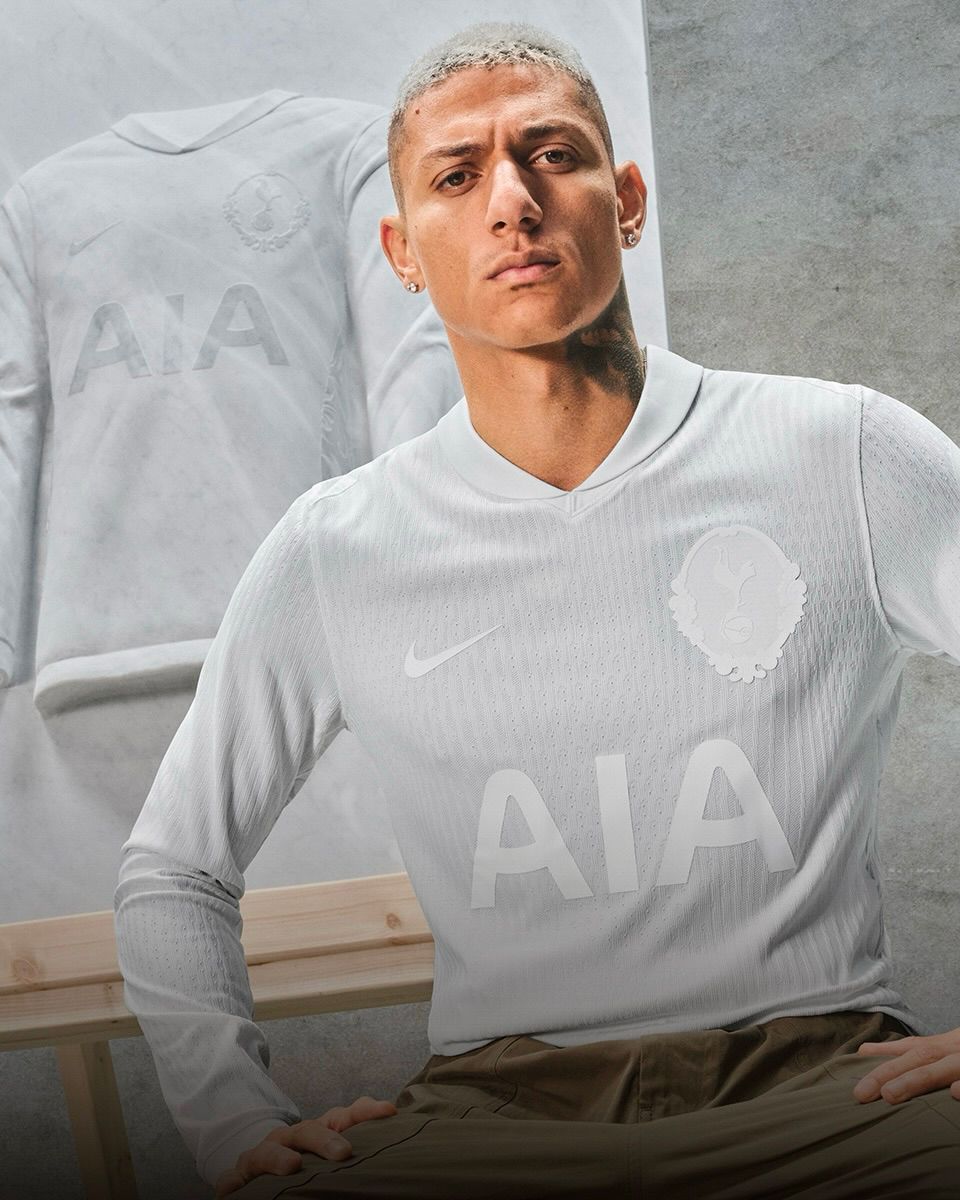

The iconic 'Jumpman' logo, featuring Michael Jordan's silhouette soaring through the hoop, adorns Exhibit 2, which is the document outlining the guidelines created by the DHS investigative team to help federal agents identify members of the Tren de Aragua. This text has been circulated among law enforcement agencies, urging them to apply its recommendations at border crossings.

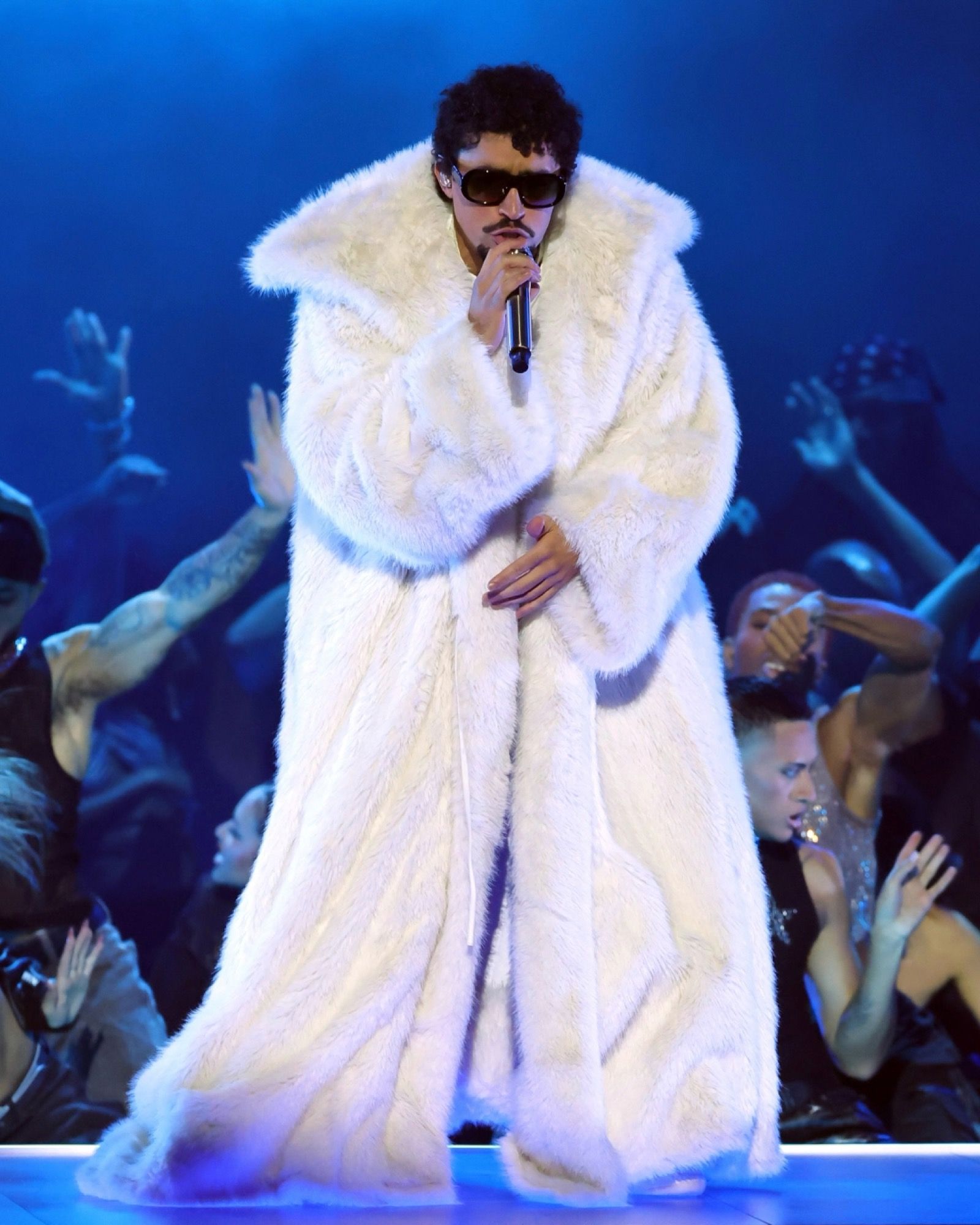

The document contains various potential 'clues' for agents to consider, such as background information, social connections, tattoos, clothing, and additional indicators, each assigned a point value. For instance, a 'Jumpman' tattoo earns four points, as do other tattoos like crowns, trains, and AK-47s. Wearing a Bulls jersey or a pair of Jordan sneakers also nets four points, while having direct telephone communication with confirmed gang members scores six points. Other items, like merchandise from artists connected to gang culture, such as Anuel AA, are worth two points, and sharing 'suspicious' posts on social media counts for one point. Once an individual accumulates eight points, they are flagged for booking and may face deportation.

This approach is rooted in the Alien Enemies Act, a 1798 law that was revived by Trump to categorize hundreds (if not thousands) of Venezuelan migrants as a 'national security threat.' This allows for their expulsion or deportation without formal charges, trials, or sentences, based solely on an executive order that effectively transforms visual suspicions into operational guidelines.

Reactions

The gravity of the situation became apparent in court, where federal judge James Boasberg issued a ruling to suspend the expulsions, noting that the law stipulates conditions like a declaration of war or invasion. However, this ruling did not halt flights heading to El Salvador, Ecuador, and Venezuela. The government's chilling response, recorded in court, was, "We don't care, we do what we want." In the meantime, over two hundred Venezuelans have been relocated abroad within a few weeks. Some appeared in videos shared by Nayib Bukele's Salvadoran government, filmed inside the notorious CECOT maximum-security prison, displaying tattoos as a sign of affiliation. As expected, the backlash was severe.

Bill Hing, a law professor at San Francisco, called it "outrageous" to identify gang members based on tattoos or aesthetic traits. Journalist Ronna Rísquez described the situation as filled with "institutional fantasies," labeling Exhibit 2 as a tool of political xenophobia. Criminologist Andrés Antillano noted that the criteria used reveal a disconnect between political narratives and criminal realities. The British newspaper The Independent reported that many images included in the document were sourced from the internet and taken out of context, with some originating from the websites of British and Indian tattoo artists, such as an "HJ" tattoo from a New Delhi artist representing the initials of a friend and his wife. Despite these criticisms, the ongoing process remains unchanged, and the Department of Homeland Security has not been persuaded to reconsider its standards.

Past references

The link between sports logos and gang culture in the United States is a long-established phenomenon. Over the years, various criminal organizations have embraced team colors, logos, and uniforms as symbols of their identity. Consider a few notable instances: the Rollin' 60s Crips were known for donning Seattle Mariners hats, using the letter "S" and the color blue to align with their name and symbolism. Similarly, the connection between the Latin Kings and the Los Angeles Kings was almost instantaneous. Beyond professional sports, we also see references such as the Vice Lords’ appropriation of the Louis Vuitton logo—akin to the Chicago White Sox jersey. The Gangster Disciples took the name “Hoyas” and cleverly reinterpreted it as an acronym for 'Hoover's On Your Ass,' even transforming Georgetown's mascot collar into a six-pointed crown. Additionally, there are numerous examples of gangs using sports affiliations to signify territorial claims.

Once these connections come to light, brands rarely address them directly. This is largely due to market and reputational concerns — similar to the reason Nike pulled a balaclava from its line in 2018 after facing criticism for seemingly endorsing London gang culture. As is often the case, major companies tend to overlook these associations. Recent events, however, indicate that the focus is shifting away from the brands themselves and onto those who wear their products. This applies even to one of the most iconic uniforms in global sports and to beloved figures like the greatest basketball players, as well as widely popular items and behaviors. For example, if you're Venezuelan and find yourself targeted by US immigration, a single 'wrong' outfit or a few questionable associations can lead to being labeled a member of the Tren de Aragua, effectively erasing your identity.