Kings League Italy, A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again Here's how the first Italian edition of Gerard Piqué’s tournament went

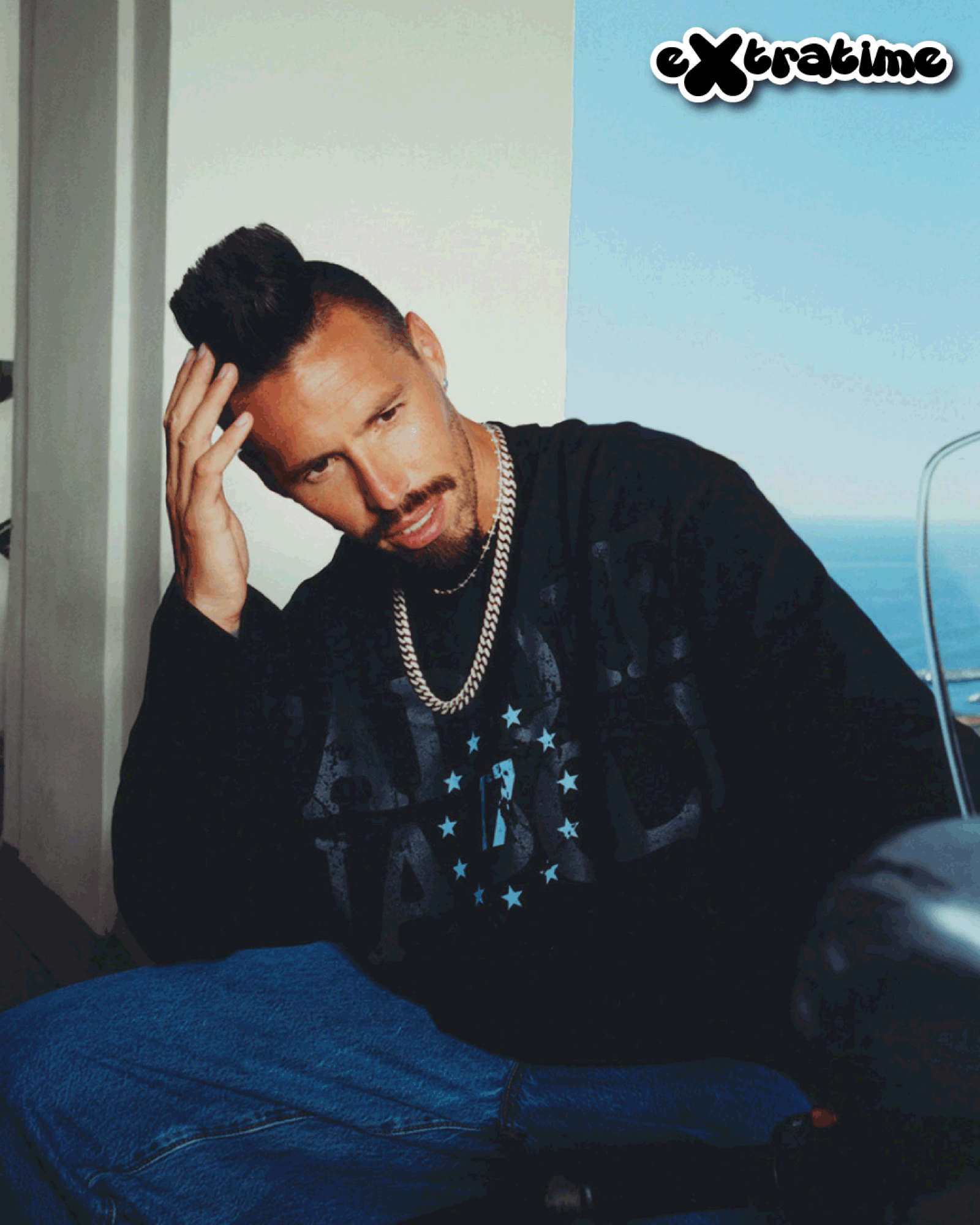

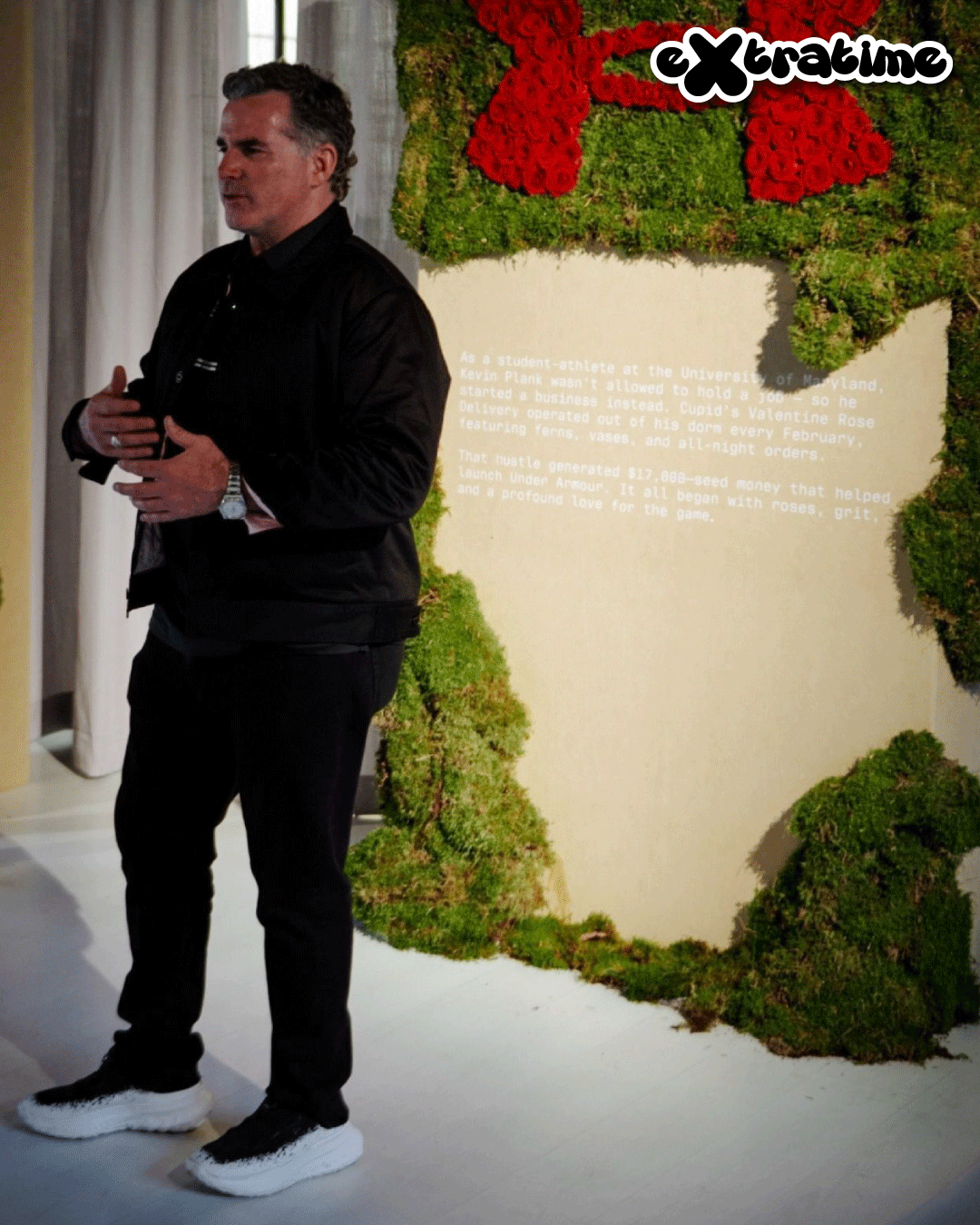

On November 18, 2024, the Kings League franchise officially landed in Italy. With a launch event held at the Torino Event Center, just steps away from Juventus Stadium, the Italian edition of the tournament founded by Gerard Piqué introduced itself with all the expected ambitions: from the appointment of Zlatan Ibrahimović as president of the Italian league to Claudio Marchisio as Head of Competition. Honestly, I couldn’t miss it. So I requested press accreditation to secure a seat in front of the stage, where Pierluigi Pardo would introduce the participating teams alongside their presidents: Fedez, Er Faina, Blur—well-known faces of Italian trash culture.

Between Pierluigi Pardo’s verve and some funny moments, what lingered was a sense of curiosity, a veil of mystery: can Kings League Italy really be a valid alternative to traditional football? Will the idea of football entertainment truly take shape through the Kings League project? Spoiler: no. Unless, dear readers, by football entertainment you mean a stupid joke, where Ibrahimović and Marchisio are given “institutional” roles in the competition without any real involvement. No presence at matches, which are played every Monday in a dilapidated Fonzies Arena; Kings League Italy, in this first edition, was a cardboard set that collapsed within moments.

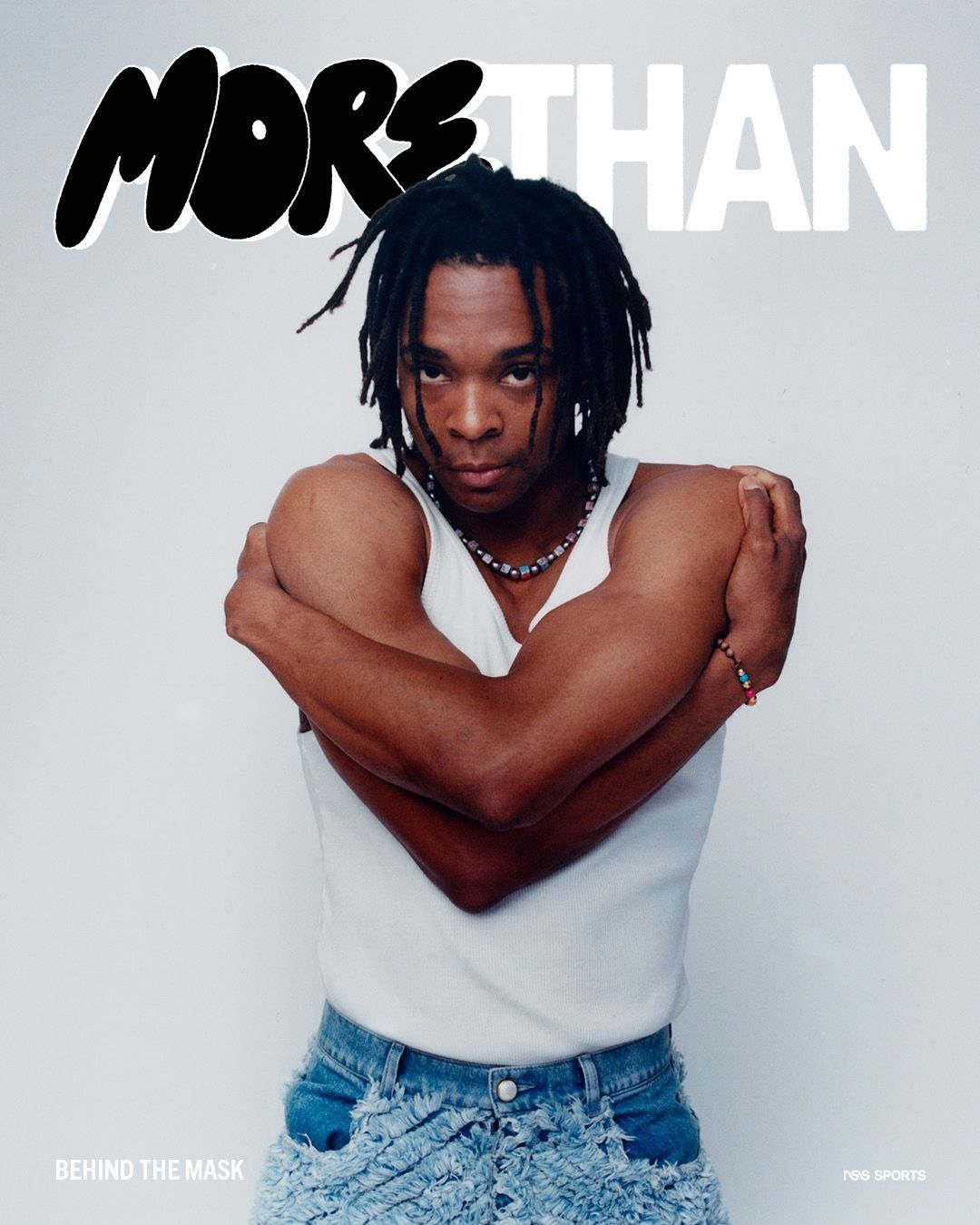

It’s worth making a comparison: in France, while AC Milan is in full managerial and performance crisis, the league managed to appoint Mike Maignan as president of the 360 Nation club, joined by Jules Koundé, Aurélien Tchouaméni, Manu Koné, Bryan Mbeumo, and Senny Mayulu. Maignan even kicked a “presidential penalty” (yes, that’s the actual term used in Kings League for a penalty taken once per match by a team president). Now that’s a proper comparison. Mike Maignan—considered one of the top five goalkeepers in the world back in 2023—taking a penalty in a competition like Kings League—where in France too the main presidents are YouTubers and content creators, with a target audience very similar to Italy’s—that’s real football entertainment.

It perfectly hits the Kings League’s mission: to increase the unpredictability of matches while drawing in younger audiences. Mike Maignan’s penalty is football entertainment. Because it’s surprising, fun, unconventional. It’s newsworthy. (Also) Because it’s hard to imagine just how complicated it is to involve professional footballers of that niveau in such events. Fedez taking a penalty, on the other hand, is just Fedez taking a penalty.

6 endless hours at Fonzies Arena

@nsssports Ci manchi, Radja. #seriea #kingsleague #radjanainggolan #enerix #erfaina suono originale - nss sports

But to reach these conclusions—harsh, severe, realistic—I had to experience a Kings League matchday. I really wanted to understand how six hours at the Fonzies Arena would unfold, watching every scheduled match instead of just letting them play in the background on Twitch, so I asked for accreditation for the league’s third matchday. To clarify: I was there on the day of Radja Nainggolan’s debut for Ceasar FC, the team run by Damiano Er Faina and En3rix. It was also the day when Fedez kicked the presidential penalty, celebrated on the pitch, joined the team photo with his dog, Silvio. In short, all the ingredients were ready for a six-hour run. Six hours turned out to be a boring, poorly paced loop. This points to one of Kings League’s many issues: is it just a football pitch turned into a TV set, or does the federation genuinely aspire to have real physical relevance?

At least it was a great chance to ask a question: why would a Kings League fan want to attend these matches in person? In a run-down venue where the snack bar line overlaps with the entrance line, where there’s not even entertainment between matches. But more importantly: how is Kings League Italy supposed to bring young people closer to football? And how are they supposed to develop any real passion for the sport through the Kings League? Few things in my life have been as dull as Bomber Picci’s constant complaints during the match I attended—the league’s supposed hero, embodiment of all small-town striker clichés (in Italy, we call them "Bomber").

A stereotype inseparably tied to amateur Italian football, which we just can’t seem to live without. And one that unfortunately returns in the Kings League’s narrative—or rather, its farce. In less than an hour of gameplay, Bomber Picci managed to make me relive the toxic atmosphere of grassroots football. It brought me back to when I decided to quit playing more than ten years ago, at 16. Even back then, parents shouting from the stands—always ready to defend their kids with cheap complaints toward the coach or referee—filled me with deep sadness, it was so annoying. Provincialism in its purest form.

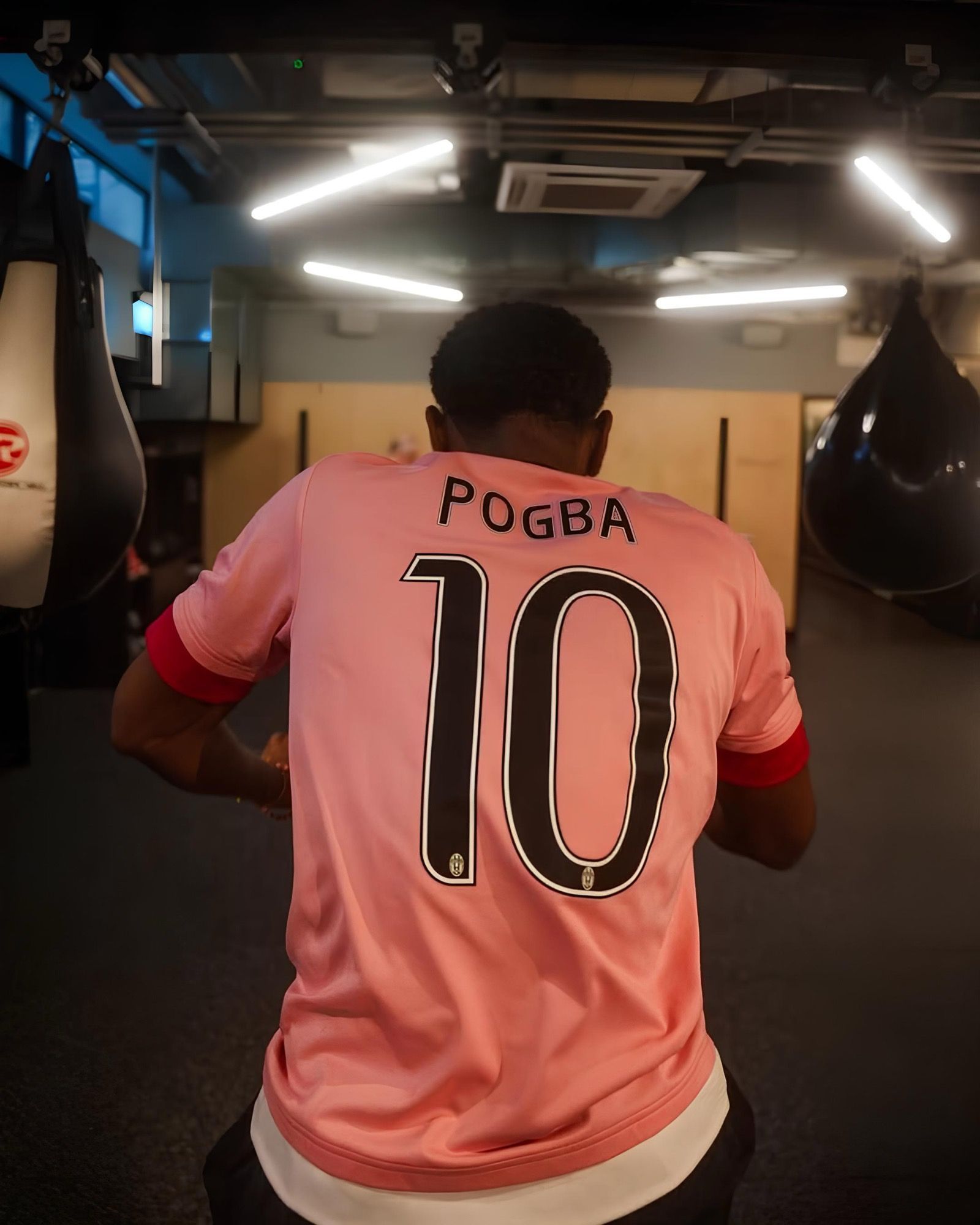

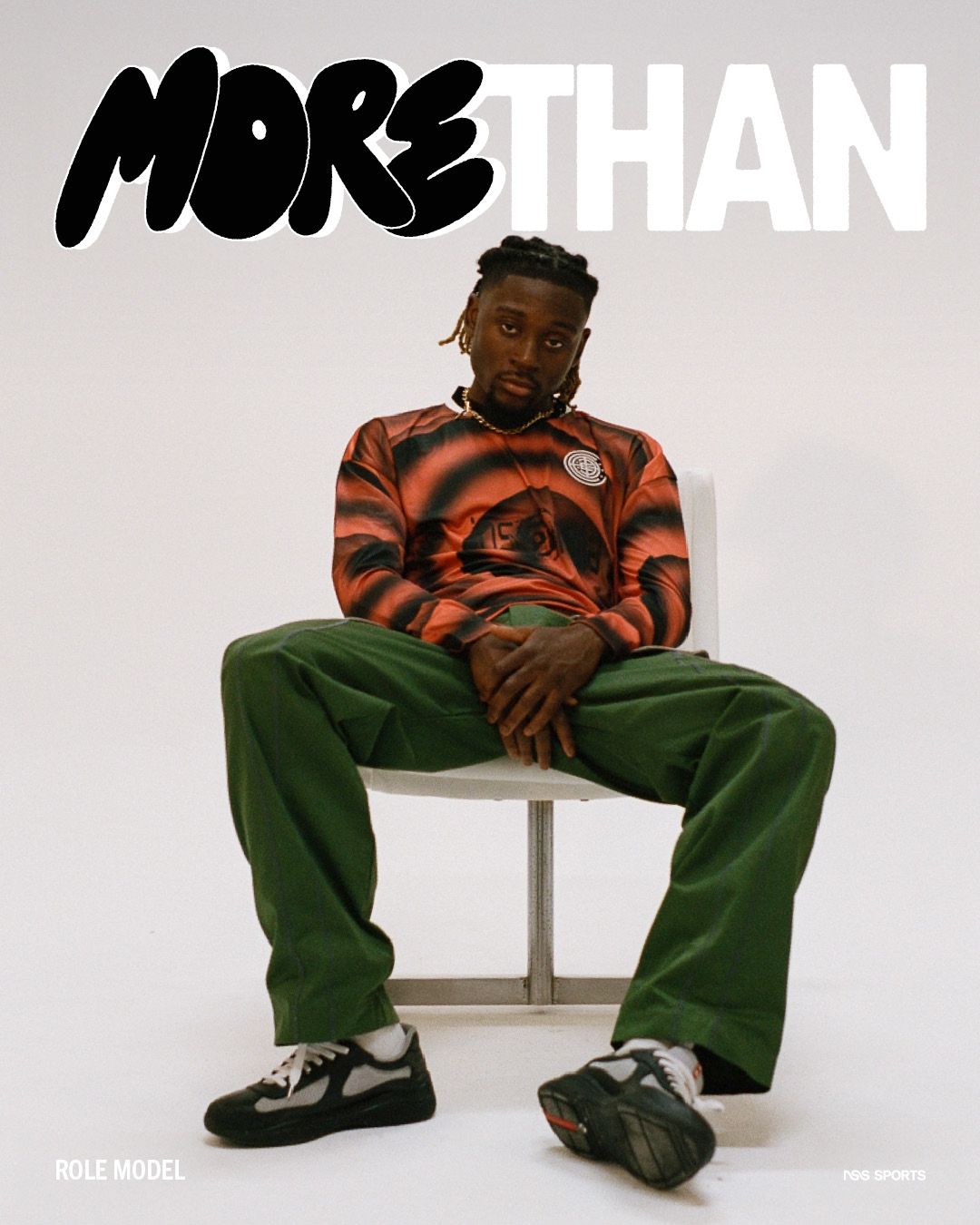

Bomber League Italia

At this point, it becomes clear how the Kings League’s stated goal—winning over a new young audience—loses credibility. The "bomber" stereotype is clearly outdated, yet it remains central to the Italian version of the tournament. Then there are the legends—former Serie A players who joined the first edition of Kings League Italy: Jacopo Sala, Ciccio Caputo, Emiliano Viviano, and Radja Nainggolan: instead of warming up for the match, chose to vape an e-cigarette on the sidelines. These are players from another generation, with no media power, except perhaps for Nainggolan—and more for his off-pitch controversies than sporting merits, such as his arrest for drug trafficking just weeks before his league debut.

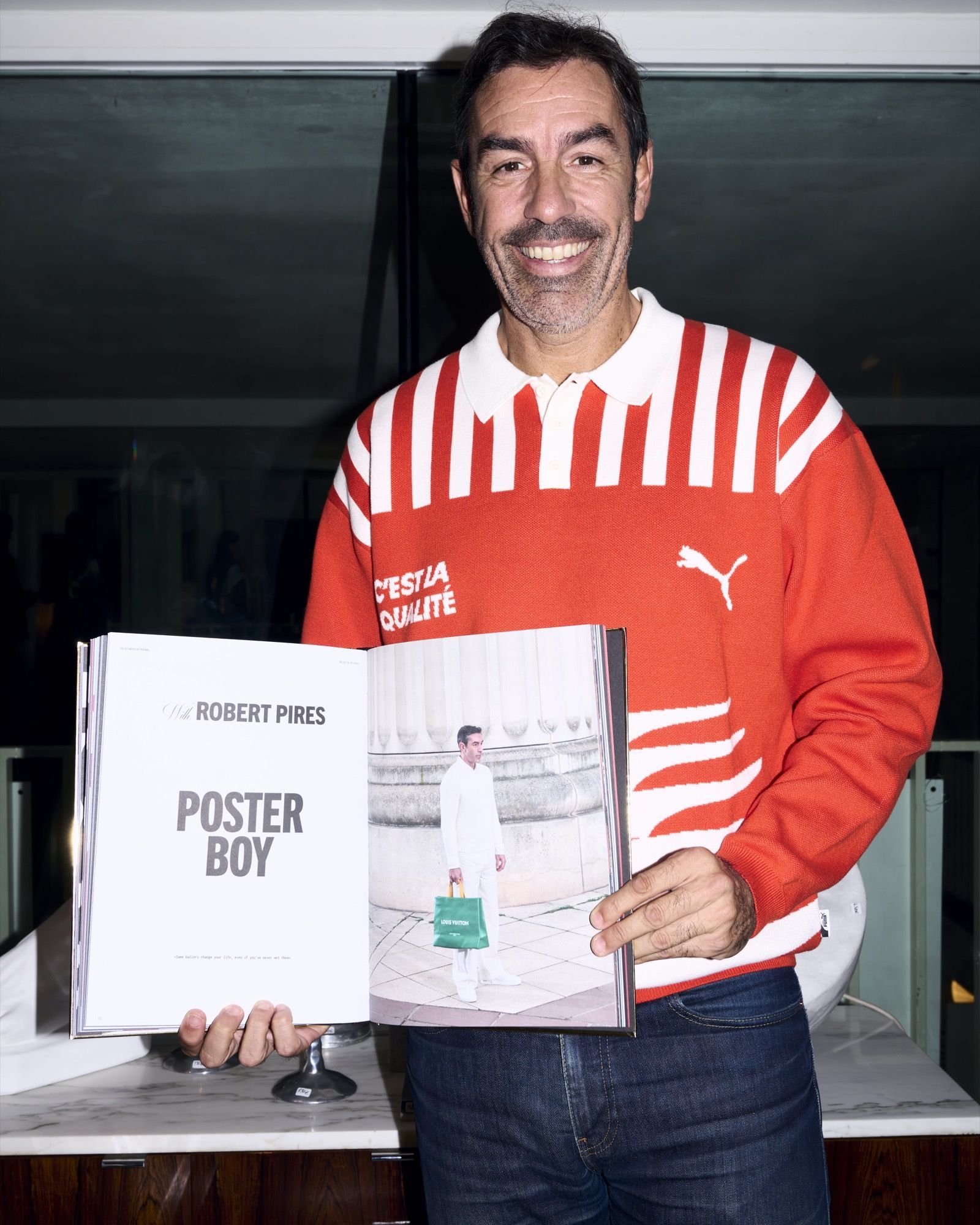

It’s a football narrative that once again falls into the trap of nostalgia, revealing how this sport has diverse, fragmented, and disjointed audiences. Which, to be clear, is also part of its charm. However, in this mix, the younger generation audience—the one the Kings League should be targeting—seems to matter far less than the others. And here the circle closes: why, then, shouldn’t we compare Kings League Italy to the French version? How can anyone believe they’re pursuing the same goal when, on one side, there’s Tchouaméni and Koundé, and on the other, Caputo and Nainggolan? How can anyone believe that two peers, one in France and one in Italy, could be equally engaged by these players? It clearly shows Italy’s weak and uninspired star system, lacking in charisma, with zero allure, as some might say. On the other hand, it proves that in France, a vibrant and evolving star system exists—one that includes the strong, genuinely cool players like Jules Koundé.

Kings League Italia: N/A

@nsssports Abbiamo incontrato Zlatan Ibrahimovic sul red carpet della @Kings League Italia e l’unica domanda che ci è saltata in mente è stata la seguente: se tu potessi comporre una squadra a 7 come in Kings League, come sarebbe? by nsssports #kingsleague #kingsleagueitalia #zlatanibrahimovic #ibrahimovic #footballtiktok #nsssports suono originale - nss sports

It must be admitted that Kings League Italy was at least consistent in one way: it abandoned any ambition of appearing cool or aesthetically curated from the start. The kits are boring, the players involved are anything but icons, and the site’s e-commerce reflects the same indifference: considering the massive potential community brought in by creator-presidents, it’s almost surreal to see such a potentially marketable merchandise line be so graphically dull—designed like it came from a small-town haberdashery. Kings League Italy, in its first edition, was ugly but more importantly incoherent, systemically flawed—but how many people actually noticed? This article is published the day after the Finals, held in Turin’s Inalpi Arena—the same venue that hosts the Nitto ATP Finals. So let’s hope that next year, Kings League manages to borrow at least a bit of the beauty of its surroundings. Because, today, Kings League Italy is painfully far from the utopian idea of football entertainment; and more importantly, let’s hope the youngest generations don’t take it as a model—because then we can be sure that football’s audience will shrink dramatically, since Kings League Italy is neither real football nor true entertainment.