Can the America’s Cup heal the relationship between Naples and the sea? "The sea does not wash Naples"

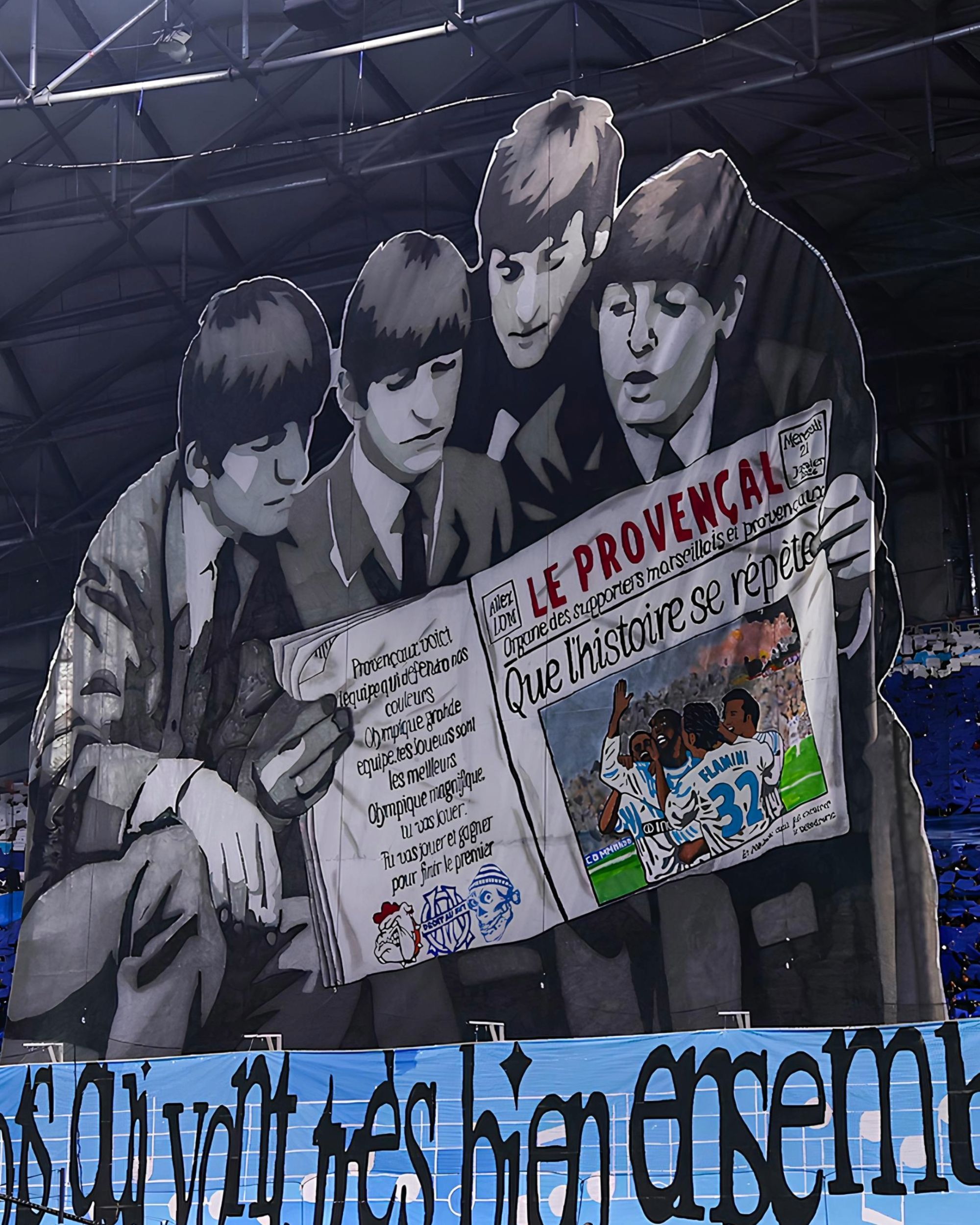

"The sea does not wash Naples" is the title of a collection of short stories by Anna Maria Ortese, published in 1953, which recounts the city’s hardships in the years following the war, but it is also one of the expressions used to frame the strange nature of Naples: a maritime city with a fractured relationship with the sea. This is not just a metaphor, but a planning reality: although the gulf embraces almost every side of the city, Naples experiences its sea mainly as a backdrop, as a promise. The sea is there, but it does not truly allow itself to be touched—also because strolling along the pedestrianized Lungomare Caracciolo benefits tourists more than Neapolitans. Unsurprisingly, the hidden sea has become one of the hallmarks of the city’s new aesthetic: from flashes of blue between buildings in Liberato’s videos, to tattoos on overly sunburnt chests at Mappatella Beach, to the private coves of Posillipo in Sorrentino’s films. Naples’ sea thus appears sudden, stolen, and often still a symbol of social disparity between those who have the privilege of access and those who can only admire it from afar.

Beyond philosophy, it is the urban-planning choices layered over centuries that have created this relationship—one that today seems to have a chance to be rewritten. With the arrival of the America’s Cup in 2027, the world’s oldest and most important sailing regatta, Naples has a rare opportunity to revive the Bagnoli area: a stretch of seafront that has been awaiting remediation and redevelopment for years. The sailing competition, which will also feature Luna Rossa—the Italian team sponsored by Prada—can therefore, from a practical standpoint, be an opportunity to regenerate Bagnoli and a way to make Neapolitans and others dream as they watch the boats dance in their own gulf.

The “cathedral in the desert”

When talking about Bagnoli, we are talking about a place where a century of Italian history has been condensed into a few hundred meters of coastline. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the area was still an urban periphery—a landscape of dunes, beaches, and countryside. In 1910, steel arrived: the great steelworks was established, destined to become one of the symbols of Naples’ modernization. Thousands of workers and entire working-class neighborhoods were built around the factory.

Expansion reached its turning point in the 1960s. The land reclamation at sea—a massive artificial infill of the coastline—pushed the plant directly onto the water, and the complex took on the name that would remain in collective memory: Italsider. The plant reached a European scale, with record production, cranes, blast furnaces, and an industrial landscape that erased beaches and redesigned the relationship between the city and the sea. Decline came in the 1980s. The steel crisis hit hard and, despite investments and attempts at revival, production ceased in 1992, leaving behind an industrial ghost wedged between Posillipo and the urban center of Bagnoli.

The America’s Cup 2027 – the urban regeneration project

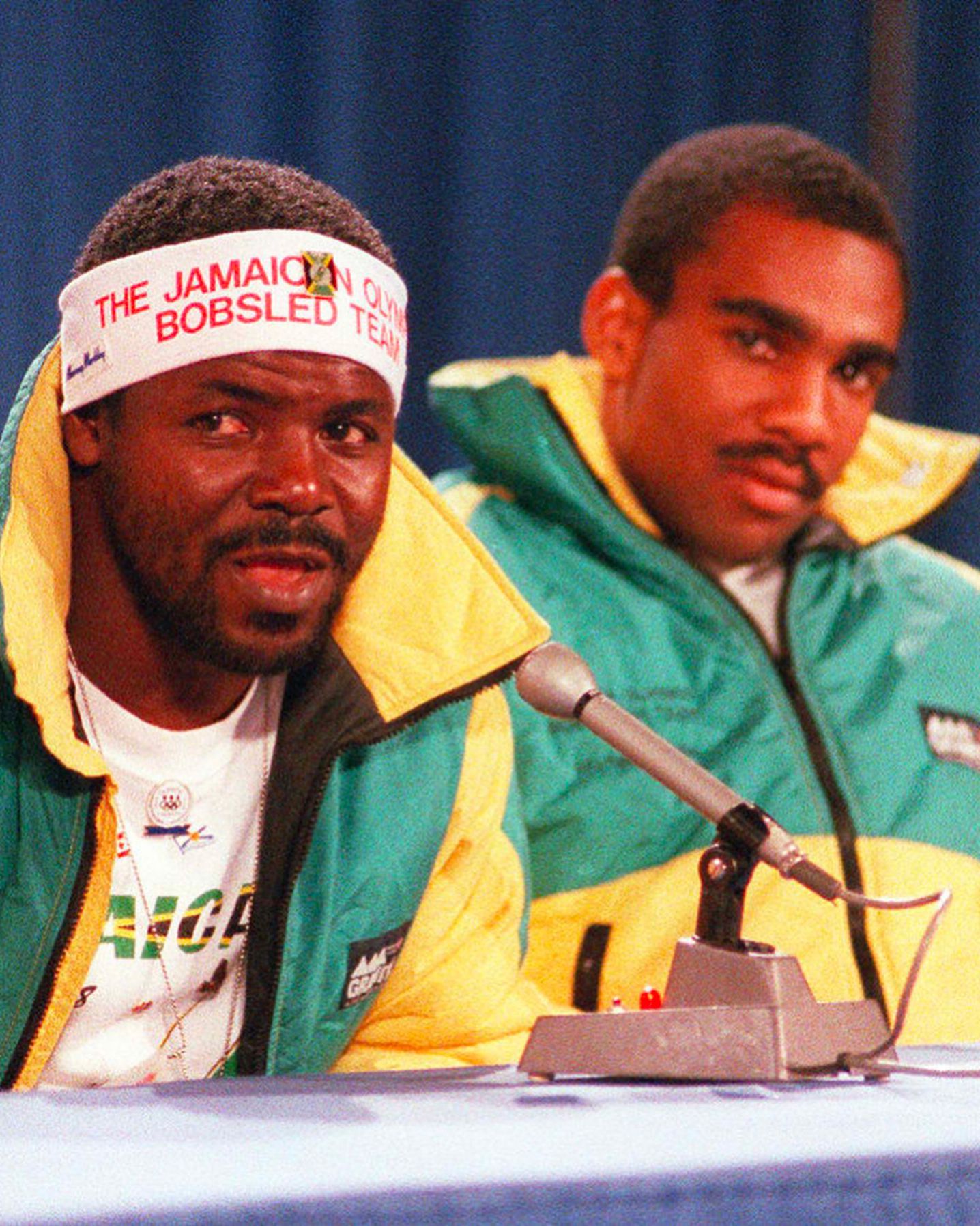

When Giorgia Meloni announced that Naples had been chosen by the New Zealand team (winners of the last America’s Cup) as the host city of the 2027 America’s Cup, initial enthusiasm was followed by doubts as to whether the city would be capable of hosting an event of such magnitude. Cities like Valencia and Barcelona used past editions of the America’s Cup for ambitious urban redevelopment projects. The heart of the intervention is the so-called Technical Base Area: a complex of infrastructures designed to host sailing teams from around the world and their vessels. This is therefore not merely a temporary setup, as the teams will stay in Naples for almost six months, up to the final challenge.

The Bagnoli plan, overseen directly by Mayor Gaetano Manfredi and approved by the steering committee on August 4, 2025, provides for an initial budget of €152 million for works at sea and on land. This amount will also serve to accelerate environmental remediation as part of the broader coastal restoration program financed by a major public investment of €1.7 billion, which will also ensure the swimmability of the waters—currently denied due to pollution.

The future

The project has not been free of controversy and skepticism, particularly regarding timelines and the future of the area once the America’s Cup is over. The main concern is the creation of a luxury harbor, reproducing a model of the sea for the few and the wealthy, thus excluding the people who live in Bagnoli and who for decades have received promises of remediation. However, the America’s Cup case shows how cities change today: all previous redevelopment projects failed, wasting enormous resources, and today the only real opportunity for public institutions with limited funds to set public works in motion is often through major international events. Milan in 2015 with Expo launched this model, which does not seem to have been replicated with the same effectiveness for the upcoming 2026 Olympics. Naples appears to have seized a historic opportunity with the America’s Cup to give a new dimension to the relationship between the city and the sea, because if the teams’ bases are in Bagnoli, the racecourse will be in the middle of the gulf, facing the seafront and the city. Even those who are not sailing enthusiasts will have one more reason to seek out the flashes of blue between Naples’ streets and watch the boats chase each other, flying over the water.