Which brands can learn from the success of 2000s surf culture? Communities before communities

Billabong, Volcom, Quiksilver, Rip Curl. Perhaps the answer to one of the most pressing questions for many brands today — the often forced pursuit of authenticity — lies hidden among these names.

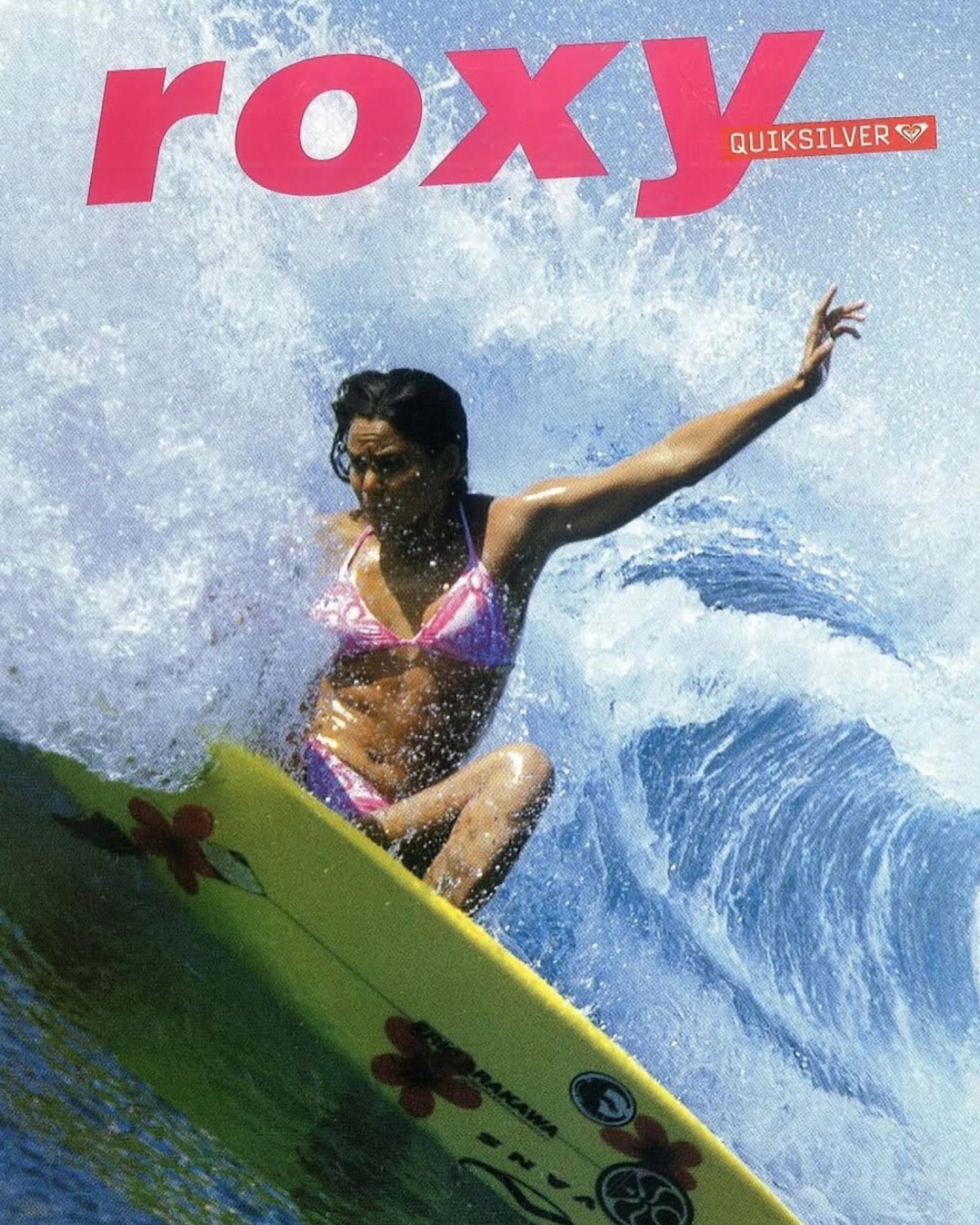

Summer is approaching, at least here in Italy. And amidst the chaos of mid-thigh swim shorts, those that once dominated the beaches of the 2000s continue to disappear: long well past the knee, with a wax comb tucked in the pocket and bold graphics just impossible to ignore. This is the story of an aesthetic, an identity, that wrote a fundamental chapter in surfwear all around the world. But what was the power of these brands? What led to their inevitable decline? And how could their business model be revived and perhaps reimagined today?

Surfwear taught us that true identity can only be born from those who genuinely live a culture. Today, activities like running seem to want to learn that lesson — but first, some steps must be retraced before getting to the point.

History and DNA of Surfwear Brands

First and foremost, the strength of those brands lay in being founded and led by people who fully lived the sport and the lifestyle surrounding it. In the case of Quiksilver, for example, we’re talking about a classic entrepreneurial fairytale: Alan Green started the business in his garage in 1968, producing surf wetsuits. A similar path was taken by Rip Curl, founded in 1969 by two Australian surfers, Doug Warbrick and Brian Singer. Volcom, on the other hand, was born with a slightly different vision: founded in 1991 by Richard Woolcott and Tucker Hall, it focused from the beginning on a more transversal identity, rejecting narrow segmentation and remaining a point of reference for skateboarding, snowboarding, and surfing, aligned with the passions of its founders and their love for board sports.

It’s no coincidence that the trend that gave rise to most of these brands dates back to the late 1960s — a pivotal period for the hippie movement, which inherently rejected institutions, rules, and consumerist norms. So, what sport better than surfing — extreme, free, practiced on a board — could embody this anti-establishment spirit? What discipline better than surfing could merge with the lifestyle of those who practiced it not for competition, but as a form of escapism and rebellion?

Two key aspects of surfing and board sports have long been romanticized and rightly celebrated in pop culture, especially during the ’90s and 2000s: the power of community and the connection with nature. Films like Lords of Dogtown and Step Into Liquid, thanks to Stacy Peralta’s vision, highlighted these elements respectively. While the second — a bit hippie but still relevant — continues to be evoked, it’s mainly the first, the community aspect, that many brands today are trying to rediscover and emphasize.

Running as the New Surf?

In short, some style codes of surf culture seem to be making a comeback, especially among running-related brands. In this field, the community — understood as a sense of belonging and togetherness — is a crucial element to include in brand storytelling to express and strengthen identity. It’s a trait often missing in the communication of many other sports, which tend to rely on different, though still valid, strategies as they attempt to build their own communities.

How many times have we heard expressions like “building community”? But what does it really mean? It means growing an audience organically, capable of developing a real sense of belonging — just like surfing, which has always boasted this quality, especially in its amateur form, long before it reached competitive levels.

To say that running is very different from surfing, apart from the community aspect, is not entirely accurate. The similarities are many: the narrative surrounding the runner is increasingly resembling that of the surfer, to the dismay of traditionalists. While the aesthetics remain clearly distinct, amateur runners and running clubs express a kind of punk attitude in their own way. An attitude that often goes beyond health: after a community run, a craft IPA at the nearest bar is a must. And it’s the amateurs, even more than the professionals, who give strength to this spirit, communicating the essence of running, which is evolving from a physical activity into a true movement — appreciated also because it manages to make the sport feel free (and punk), in contrast to the rigid conventions that defined it just a few years ago.

The Decline of Surfwear Brands in the 2000s

The decline of surfwear brands began when they became corporate: Volcom, for instance, became Volcom Inc. in 2005, was acquired by Kering in 2012, and then by Authentic Brands Group in 2019. In this transition, part of their identity and authenticity was inevitably lost, and much of their aesthetic appeal completely disappeared.

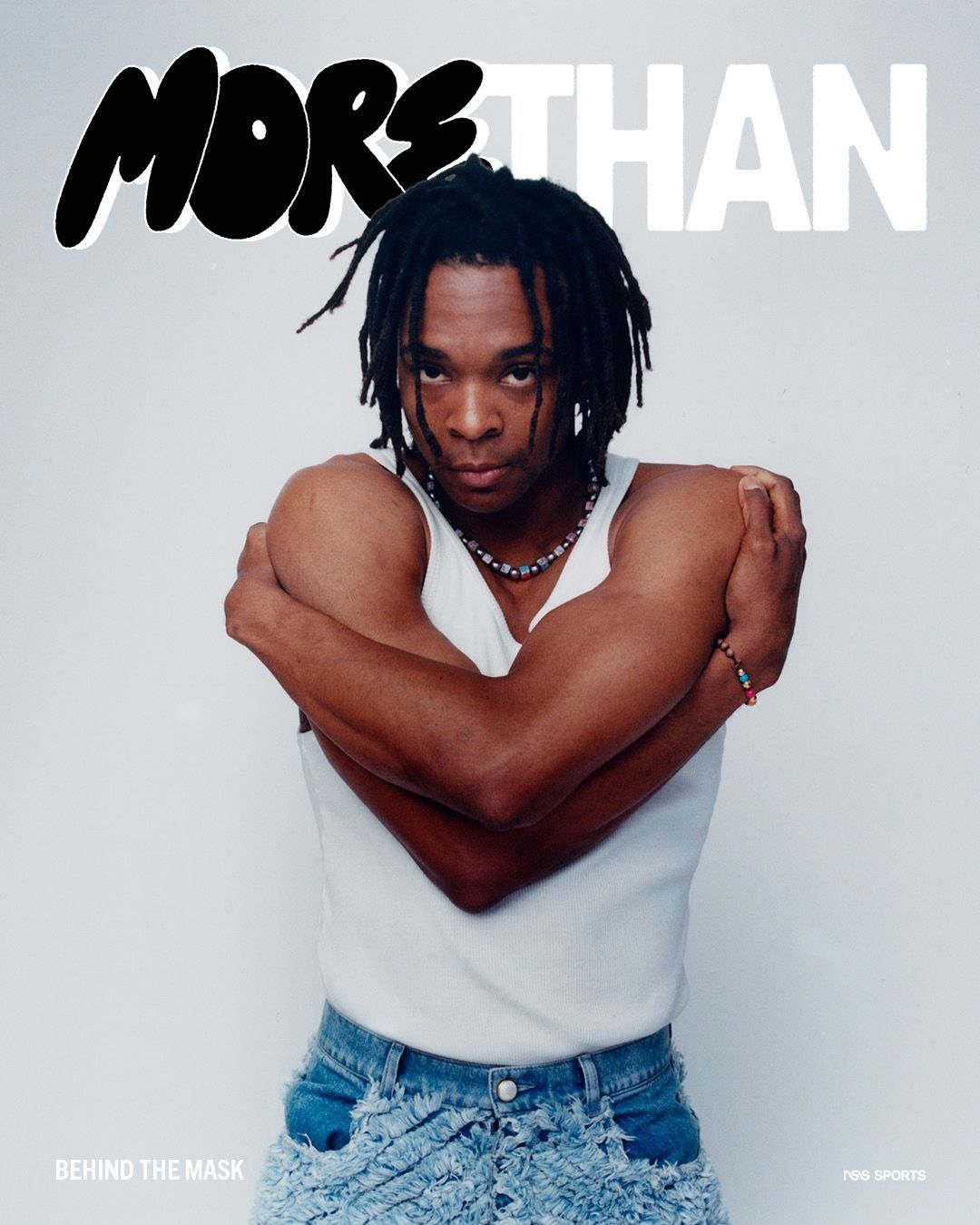

Despite this, brands like Volcom continued to digitize the community spirit. The brand founded by Woolcott and Hall launched Volcomunity, a digital space dedicated to the brand’s ambassadors — singers, models, and designers — who shared their lives through a blog. Natalie Suarez, Jennifer Herrema, Billie Edwards, Elle Green, Mike Correia, Stephanie Cherry, Amy Smith, Zoe Grisedale-Sherry, and Hannah Logic were just some of them. And it is precisely with digitalization that another factor contributing to the loss of appeal for these brands emerged: the radical shift in how athletes are portrayed. With the disappearance and irrelevance of independent industry magazines, Gen Z has lost its points of reference and, consequently, the desire to wear those brands.

On one hand, from a stylistic perspective, there is a sense of nostalgia for the proportions of older garments — like the swim shorts that no longer exist in the same form today. On the other hand, even brands now owned by major luxury groups are finding ways to reinterpret those codes: maybe shortening the shorts by a few centimeters above the knee or cutting them just at the kneecap. The distinctive traits that once made them stand out in the sportswear-turned-lifestyle landscape remain, at least in part, recognizable. But what endures most is the sense of unity and belonging — a value that brands are now striving to bring back to the forefront.

From Hoka to On, and Satisfy — founded by Brice Partouche — running (and outdoor) brands possess a strength they must never lose if they want to remain true to themselves: a deep understanding of the real essence of the lifestyle they represent.