WWE's complicated relationship with product placement The ring has turned into a huge billboard

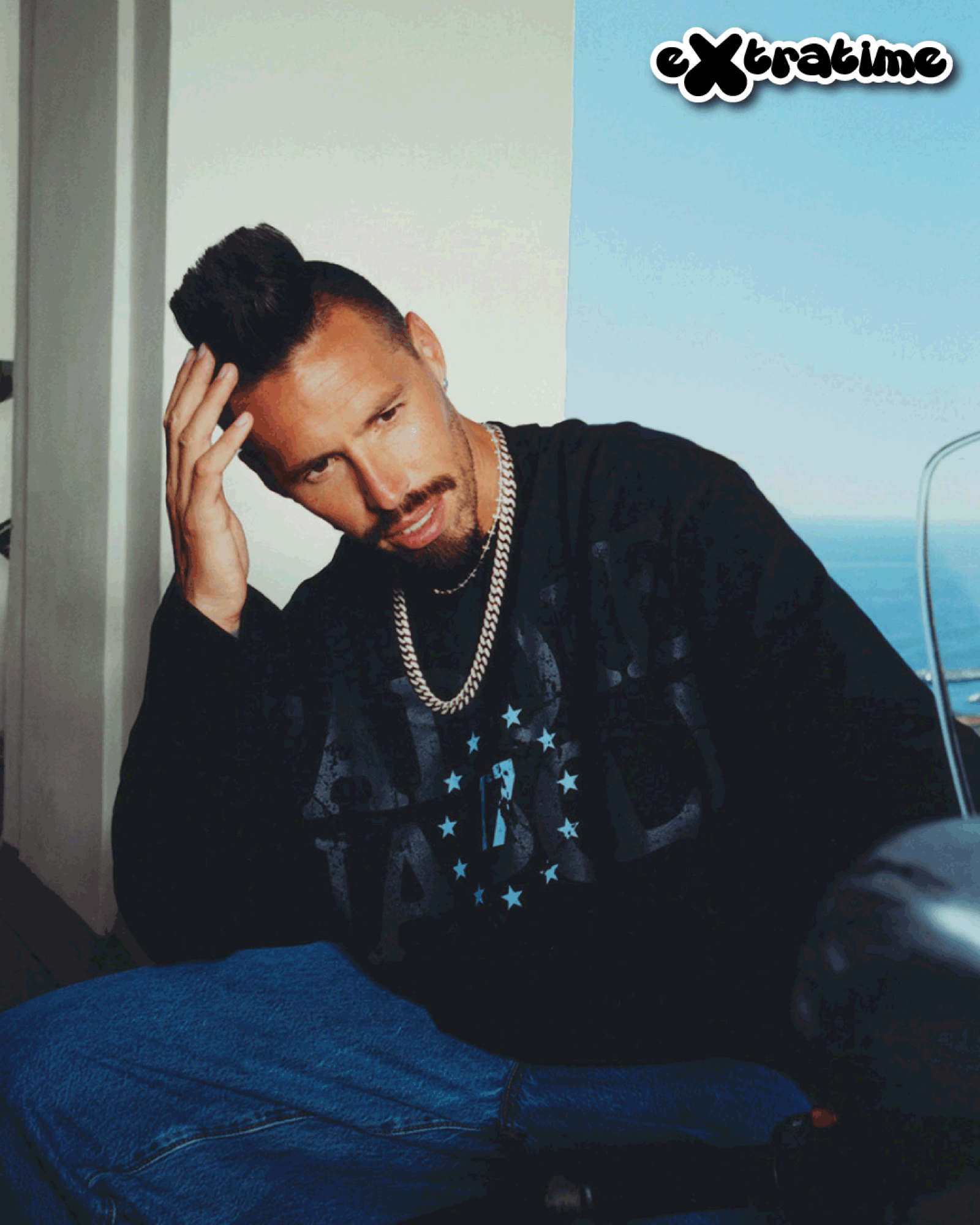

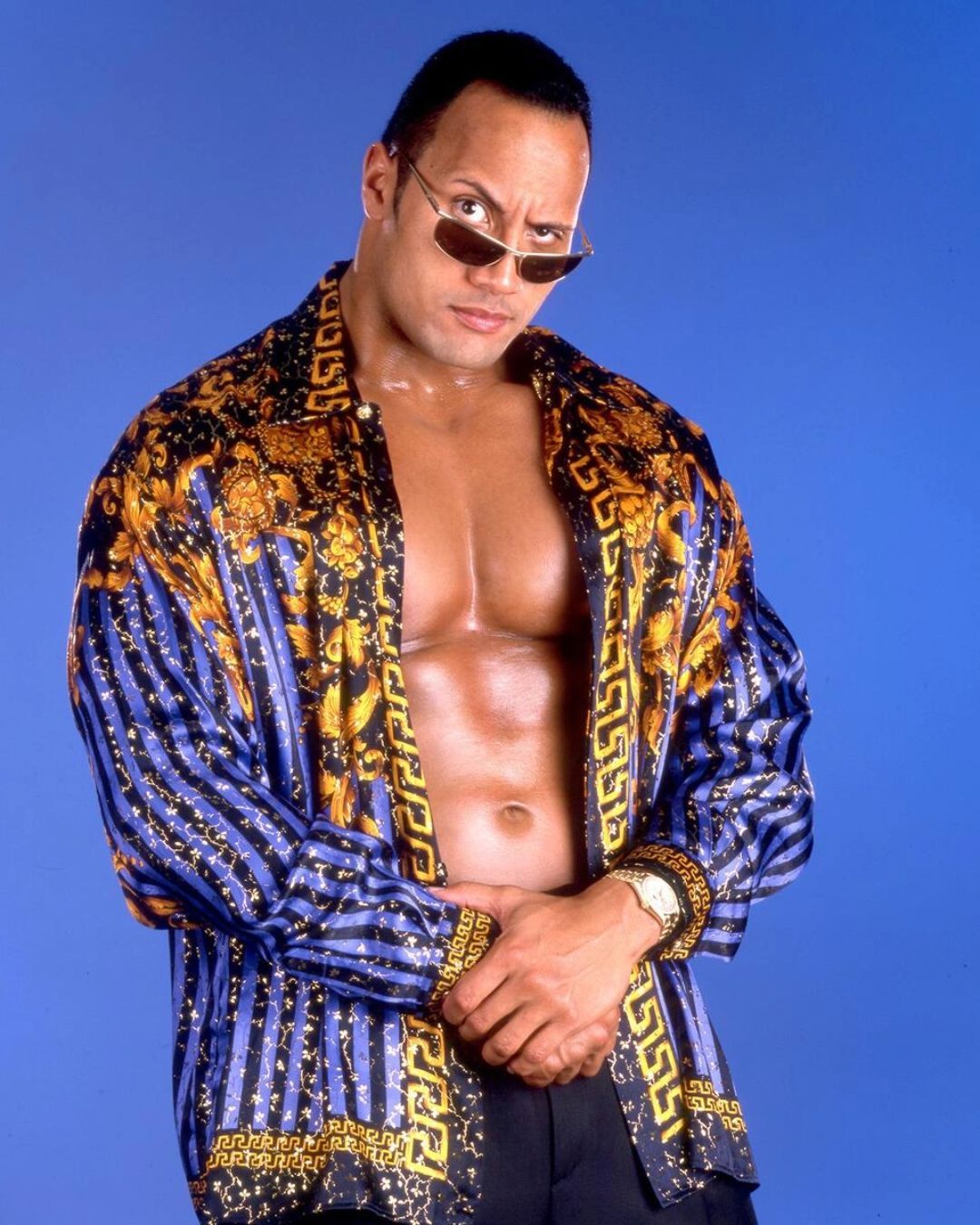

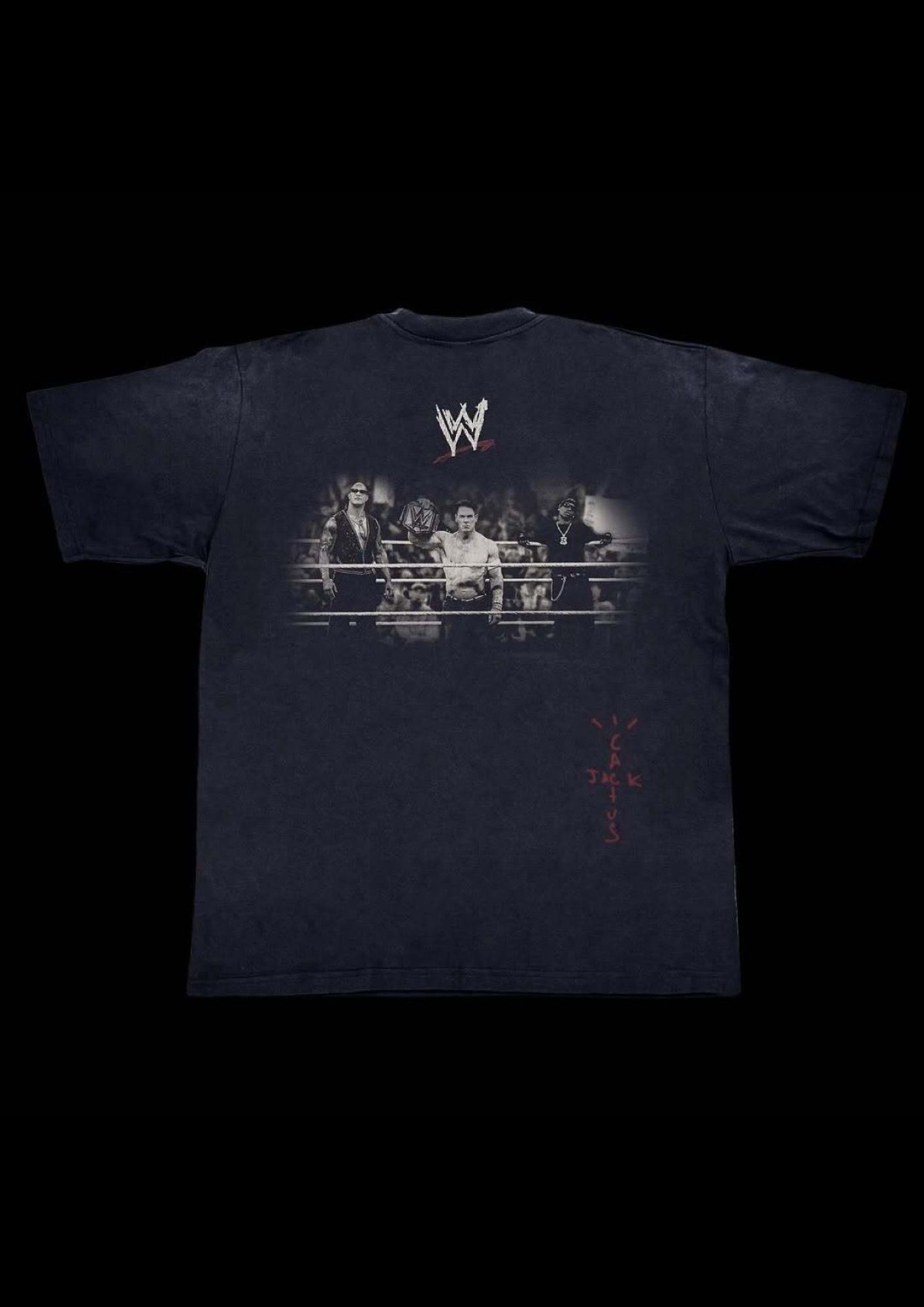

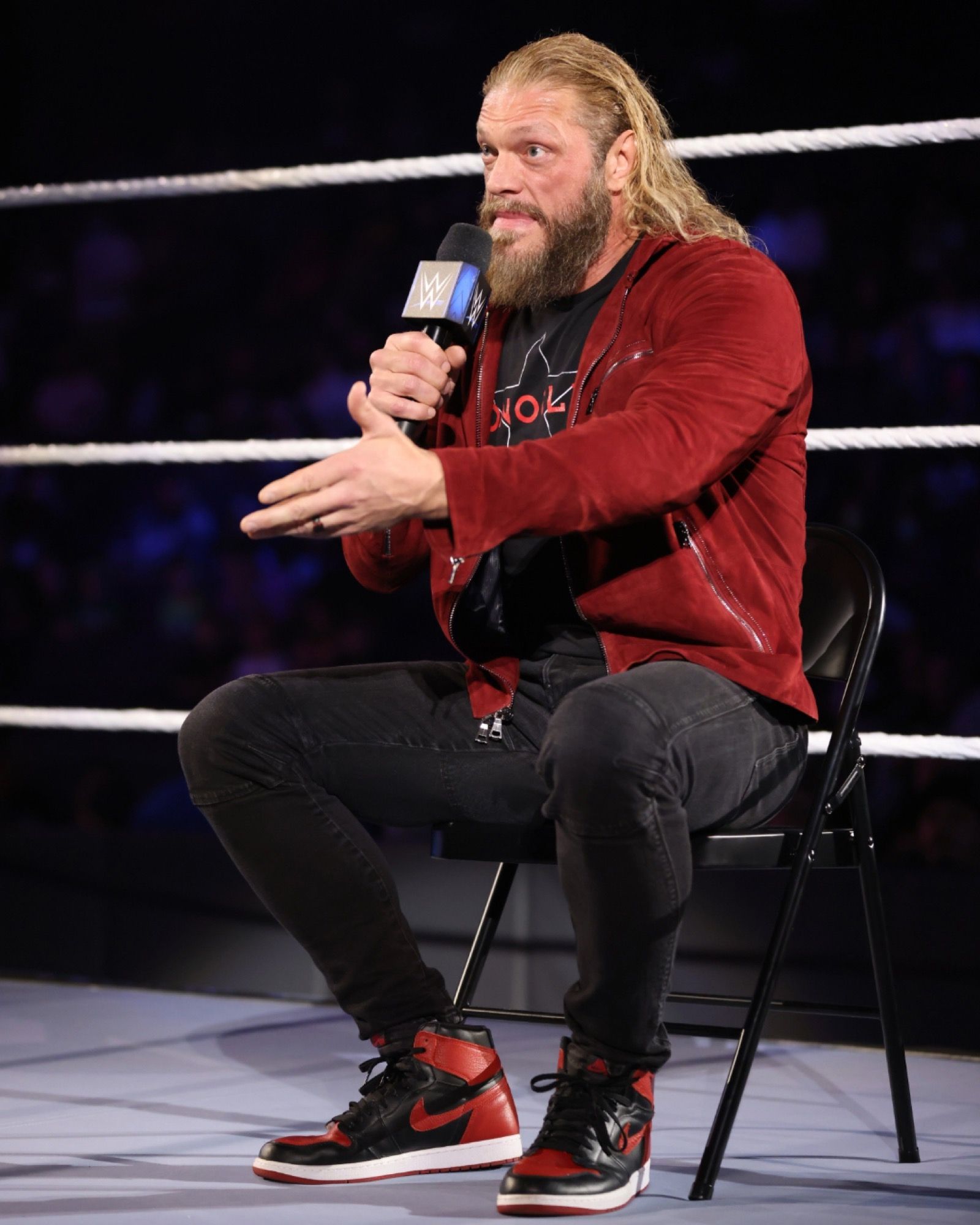

The wrestling world will remember 2025 for two historic events: the death of Hulk Hogan and John Cena’s heel turn, the first real plot twist of the farewell tour that will mark the retirement of the Boston-born wrestler at the end of the year. In one of the feuds that followed the low blow with which Cena, prompted by The Rock and Travis Scott, hit Cody Rhodes, WWE decided to recreate the Summer of Punk, the 2011 storyline in which CM Punk, to keep it short, definitively transformed into an anti-hero, a wrestler ready to go against the establishment by defeating John Cena for the title in what was supposed to be his last match before leaving WWE at the end of his contract. One of the most important moments of that storyline was the so-called PipeBomb, a promo where Punk, with Cena laid down lifeless in the corner of the ring after being slammed through a table, launched into a tirade against everyone and everything. An unprecedented stream of consciousness for the time, in which the fourth wall was broken, independent federations were mentioned, and wrestlers were referred to by their real names rather than their stage names.

@wwe This was a moment over a decade in the making for #JohnCena #WWE #CMPunk original sound - WWE

That iconic scene was recreated in 2025 on the eve of the pay-per-view Night of Champions held at the Kingdom Arena in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: CM Punk lying in the ring after smashing through a table and John Cena holding the microphone delivering a speech that point by point echoed the same ideas Punk expressed in 2011, this time from Cena’s point of view. The image is evocative, full of meaning, the perfect balance between the contemporaneity demanded by storylines and the nostalgia that never leaves wrestling fans, often children who have grown into adults. The low-angle shot perfectly captures the energy of the moment and the crucial turn in their storyline, with Punk now in the role of the babyface and Cena as the villain willing to take any shortcut to gain an advantage. There’s only one detail that spoils the image: the huge Slim Jim patch placed on the table.

There’s a bit of WWE in this product placement

It all started with Logan Paul. Prime, the energy drink line he co-founded with KSI, became the first brand in March 2024 to strike a commercial deal with WWE allowing its logo to appear in the ring. Until then, the federation’s squared circle had been sacred ground: a canvas that, despite being covered over the years with blood, beer, and milk, had remained untouched by sponsorships. Once that taboo was broken, product placement flooded WWE. One of WrestleMania 39’s most famous spots featured KSI dressed as a Prime bottle being “accidentally” slammed through a table by Logan Paul, not to mention the cart full of Prime bottles stationed ringside during every episode of Monday Night Raw. There was the aforementioned Slim Jim-branded table, and during the latest edition of the pay-per-view Money in The Bank, a Fire Ball-sponsored ladder made its debut, used in the event’s biggest spot by Seth Rollins. That’s not all. The classic gray canvas synonymous with the federation was replaced by a series of mats whose sole purpose is to serve as a background for any kind of logo.

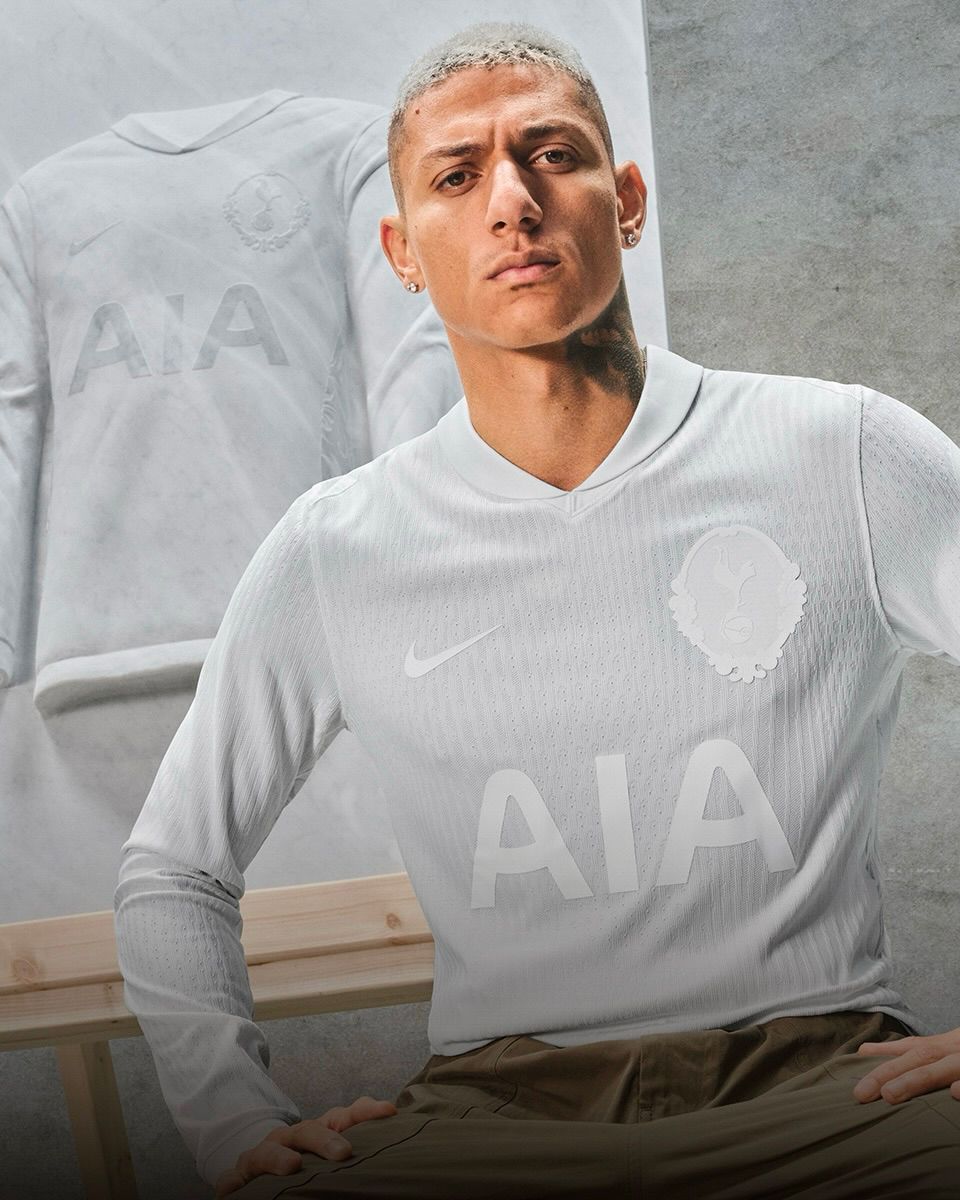

The real turning point in this story was the deal that allowed Netflix to secure the live broadcast rights for Monday Night Raw, WWE’s flagship show, and all its pay-per-views. A deal worth $500 million per year for the next 10 years. The transition from traditional TV to streaming gave WWE a unique opportunity to completely rebrand its aesthetic, at a critical time when it desperately needed to distance itself from anything associated with Vince McMahon following the 2024 allegations of sexual assault and human trafficking that led to his resignation. Today, WWE rings are marked by a large central logo, usually the company’s iconic W, and in Raw’s case, the black mat features a sponsor’s logo in each corner along with a series of writings/symbols on all sides. Depending on the event, the central logo changes. In Saudi Arabia, the W makes way for Riyadh Season, the de facto tourism board, while to celebrate the Netflix partnership, upcoming productions take the most prominent spaces. For example, at the latest edition of Saturday Night’s Main Event, the center of the ring displayed a promo for The Naked Gun, a reboot of the iconic trilogy starring Liam Neeson instead of Leslie Nielsen.

Here comes the money, here we go

While this new aesthetic embraces a more modern and contemporary vision, betraying a more traditional one, it’s only natural for WWE to embrace such commercial deals. It’s a consequence of this new era where wrestling no longer fiercely defends kayfabe, to the point where WWE itself co-produced with Netflix the show Unreal, a new series taking viewers behind the scenes, from the writers’ room to the Gorilla position, the last stop wrestlers pass before entering the ring. Moreover, if WWE, alongside TKO—the holding company born from the merger with UFC and now WWE’s owner—was able to generate nearly $400 million in total revenue in the first quarter of 2025 alone, it’s mainly because it has managed to close these types of commercial deals by offering advertising space it had never previously opened up.

All this, of course, comes at the expense of the fan experience, especially since in the U.S., despite Raw airing on Netflix, WWE continues to sell ad space, which means the three-hour show is still regularly interrupted by commercials, just like on cable TV. What’s angered fans even more is that in this constant quest for profit, dynamic pricing has been introduced—the system that allows ticket prices to vary based on demand. And with the annual show count reduced to 200 from the previous 300 to cut costs and maximize profits, ticket prices have skyrocketed. The recent European tour, which sold out regardless of venue or city, sparked widespread controversy over ticket prices. In Bologna, one of the Road to WrestleMania stops, prices ranged from a minimum of €126.50 to a maximum of €575, while tickets still available for the Monday Night Raw episode in Birmingham at the end of August start at £172 each. This obviously includes pay-per-view tickets—for WrestleMania 41, the two-day ticket cost a minimum of $900. Not to mention secondary markets taking advantage of the ticket shortage, driving prices even higher.

R.I.P. Titantrons

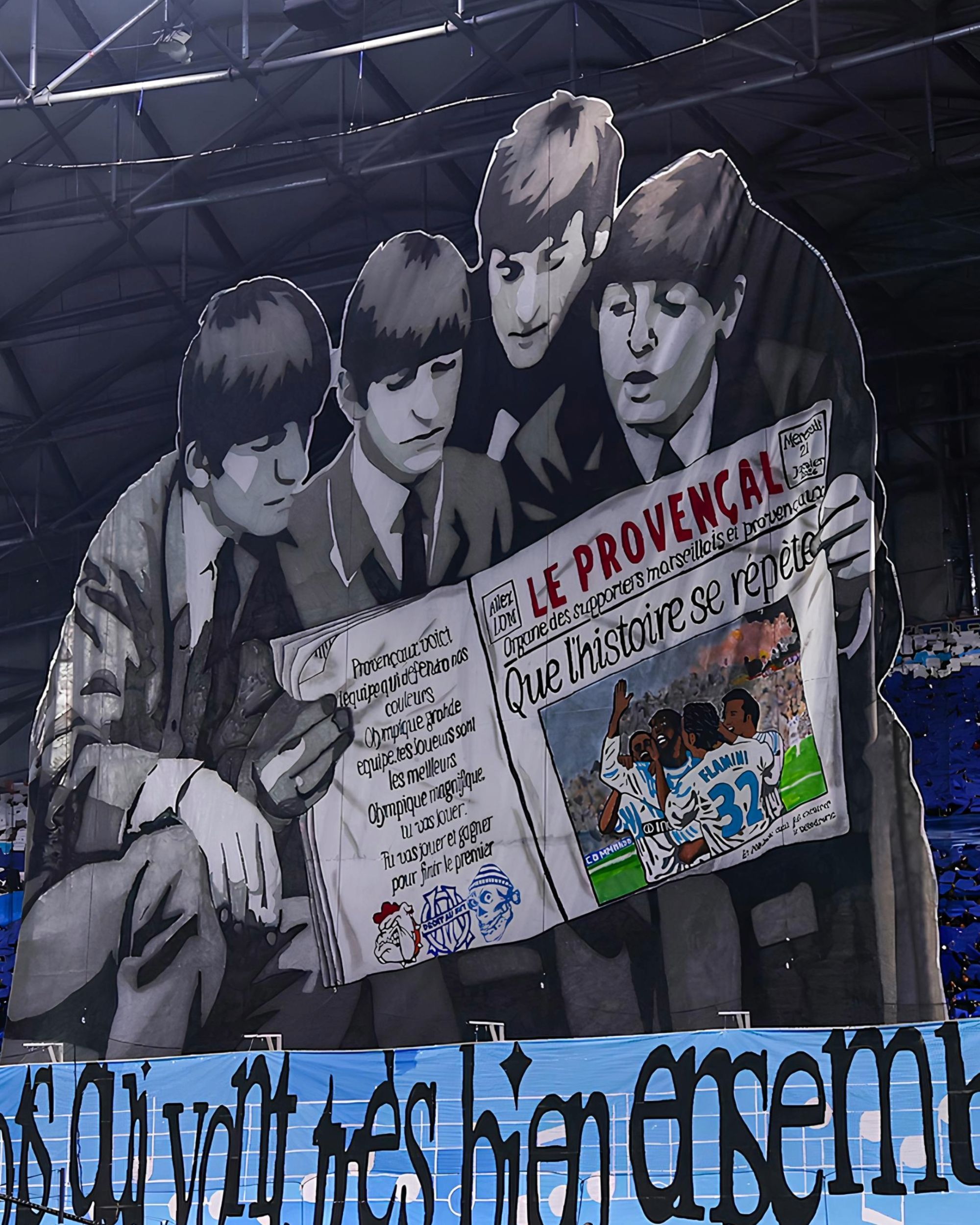

The trend of product placement—and with it the impoverishment of wrestling aesthetics—clashes with another major criticism from WWE’s fanbase: the sets are always the same. In the past, each show had its own distinct and recognizable aesthetic. For years, SmackDown’s entrance featured a giant fist smashing through a wall. Every pay-per-view had a custom entrance suited to its theme, changing year after year: armored trucks for Money in the Bank, palms and tiki bars for SummerSlam, rows of chairs, tables, and ladders hanging from the ceiling for TLC (Tables, Ladders, and Chairs). Today, only WrestleMania and a handful of other events get special attention for their stage entrance; the rest use virtually the same set: the ramp varies based on the arena, but behind it is a series of screens always arranged in the same layout projecting graphical effects. Titantrons no longer exist. WWE used to record exclusive content for each wrestler to include in their entrance package. Now that step is skipped and even the entrances are standardized: the music and pyro setups change, but the screen only shows the wrestler’s official logo.

@oldwwevideos D-Generation X 1st Titantron #wwe #dx #hhh #hbk #degenerationx sonido original - Oldwwevideos

All these choices are, understandably, part of cost-cutting strategies. Having a single stage setup simplifies all transport logistics, and not building a new set for every event prevents unused structures from gathering dust in storage. The same goes for titantrons: with one afternoon of animation work by a single person, years of a wrestler’s activity can be visually covered. It’s a business decision, and from that standpoint, WWE is thriving. And it’s not just about money—it’s about perception. Whereas WWE once ignored other federations, today not only does it do business with them—as seen with the acquisition of Mexican federation Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide—but also welcomes wrestlers from other promotions like TNA, even returning the favor by sending WWE talent to outside shows. A scenario unimaginable just two or three years ago. Furthermore, where wrestlers once seemed eager to leave WWE, now they’re lining up to return—like Rusev and Aleister Black. And WWE now is the place to be for free agents and top stars from rival promotions.

So yes, things are going great—but there’s still the feeling that something’s been lost. A sense of aesthetics that allowed for detail and finesse. Wrestling audiences are mostly people who want something in return for their time. They hope to be rewarded for their emotional investment. That reward includes the attention to elements that might seem minor but actually make the difference between a standardized product and one crafted with care. The era of custom entrances is over, and it would be unfair to ask WWE to turn back, falling into the nostalgia trap. The feeling that something is missing comes from the fact that even in this context, there have been some compelling innovations—like the new Raw logo that nods to the Attitude Era, or opening show shots that “capture” wrestlers arriving at the arena, in a nod to the tunnel fits of American pro sports. Small examples that reinforce the idea that even in an era of cost optimization, practical solutions can be found to make an event feel exclusive and special.