The Hartberg jersey (still) has the most sponsors in the world How is it possible to have more than twenty business partners in a single kit?

You’d need a special AdBlock extension to immediately recognize the new kit of TSV Hartberg, a small club in the Austrian Bundesliga. Or maybe it would make more sense to disable it, because it’s precisely the mosaic of commercial partners on Hartberg’s match kit — blue background with white inserts and adidas three stripes — that has caught attention in recent weeks. Even last season, Hartberg made headlines for a kit that looked more like a cycling jersey than a football shirt. This year, though, they’ve gone even further, with twenty-three sponsors in total across shirt (seventeen), shorts (five), and socks (one), which according to Footy Headlines sets a new record at the professional level.

Among the many patches, one in particular is hard to miss: the text #1 SPERMBOOSTER on the front, above the stomach, complete with a stylized sperm graphic. Aside from that curious detail, the overall impression is that of a walking billboard, or a NASCAR racing suit, as detractors put it on social media. Not everyone sees it the same way, however: some appreciate its unconventionality, especially in a European context, while others are more interested in the underlying marketing strategy. One thing is certain: it’s a decision that sparked curiosity and generated media coverage well beyond the local audience. In other words: a brilliant marketing move.

Behind the Scenes

The story originates in a municipality of 7,000 inhabitants in Styria, Hartberg, where the Bundesliga landed for the first time in 2018. Since then, the home team has remained in the top division, despite having a seasonal budget estimated at around €4 million, the lowest in the league. Over this time, the team has managed a few good placements and last-minute survival campaigns, with one constant: a growing number of sponsors. The first sign, one tier down, dates back to 2017: in archived photos, you can count thirteen logos on the shirt, then made by Jako; a number that rose to eighteen in the 2021/22 season, nineteen last year, and twenty-three for the upcoming one. Along with this came an ongoing and inevitable simplification of the shirt’s design, ending up with the current solid color look.

In addition to the already mentioned #1 SPERMBOOSTER, a spin-off of the fertility supplement brand Profertil, the shirt also features logos of local small and medium enterprises (Egger Glas, Steiermark, Energie Styria, Boxxenstop, Ke Kelit) and a few multinational companies like Admiral, which is also the Bundesliga title sponsor, and Thai Coco. The cost of these ads, differentiated by placement (some with double exposure) and size — for instance, Egger Glas is the main sponsor — is estimated at several tens of thousands of euros each. With a seemingly straightforward logic: the more, the better. And that’s not too far from the truth. In recent years, these mosaic kits have given Hartberg a boost in international visibility — including some less flattering awards like "worst kit of 2024" voted by Footy Headlines. As the saying goes, especially in this industry: haters gonna buy.

During the launch weekend, last July 18th, Google searches for the club increased tenfold, as confirmed by Trends data reported by OneFootball and Yahoo Sports. At the same time, the club’s posts went viral on social media, picked up by the likes of Sport Bible, DAZN, and EuroFoot. Clearly, it was a break from the norm for a club with modest numbers — both locally, with an average attendance of about 3,000 (second-to-last in the Bundesliga), and online, with 17,000 Instagram followers (lowest in the league). And so, Hartberg’s kit became an aesthetic casus belli and a tangible demonstration of how regulatory flexibility — strict or permissive — can influence the look of matchday uniforms, allowing them to become, or not become, advertising billboards.

What Do the Rules Say?

According to the Bundesliga’s Richtlinie für spielkleidung und ausrüstung (guidelines for clothing and equipment), article 4.1 states: "The number and position of advertising placements are at the clubs’ discretion, with the sole requirement that the player’s number and name remain legible." No limits on logos or occupied surface area, and this is the regulatory framework within which Hartberg and its twenty-three sponsors operate. It’s an extreme case, but not the only one: seven out of twelve Austrian top-division teams feature more than ten sponsors, with AC Wolfsberger displaying thirteen and Austria Vienna repeating the Wien Holding logo in ten different spots.

The choice is intentional. In a 2024 economic report, Bundesliga’s commercial director Bernhard Neuhold commented on the Austrian model: "Expanding the range of local partners reduces financial risks and offers opportunities for clubs with a limited market." The numbers back it up: on average, Austrian teams generate about a quarter of their revenue from sponsorships, a figure that for Hartberg rises to 35%, as confirmed by a club spokesperson (source: 90minuten.at). This logic clearly favors lower-budget teams — and it’s no coincidence that the most minimal example is the wealthy Red Bull Salzburg, whose kit displays just two logos. These are the ends of a system that, by opening the door to advertising, allows each club to design its own shirt and commercial strategy without restrictions; a reflection of a divergent approach compared to the broader European football landscape, and more akin to other sports cultures.

Overview

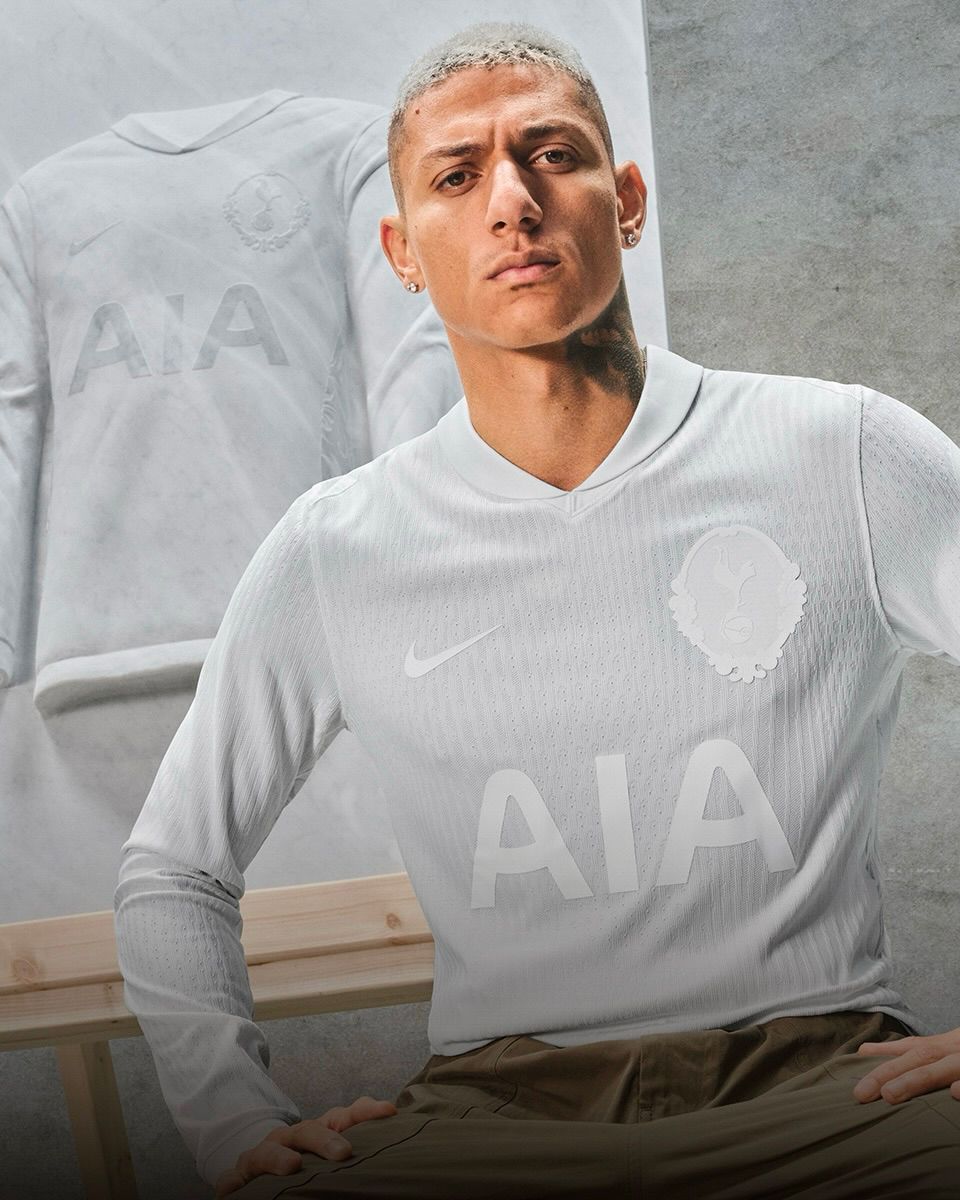

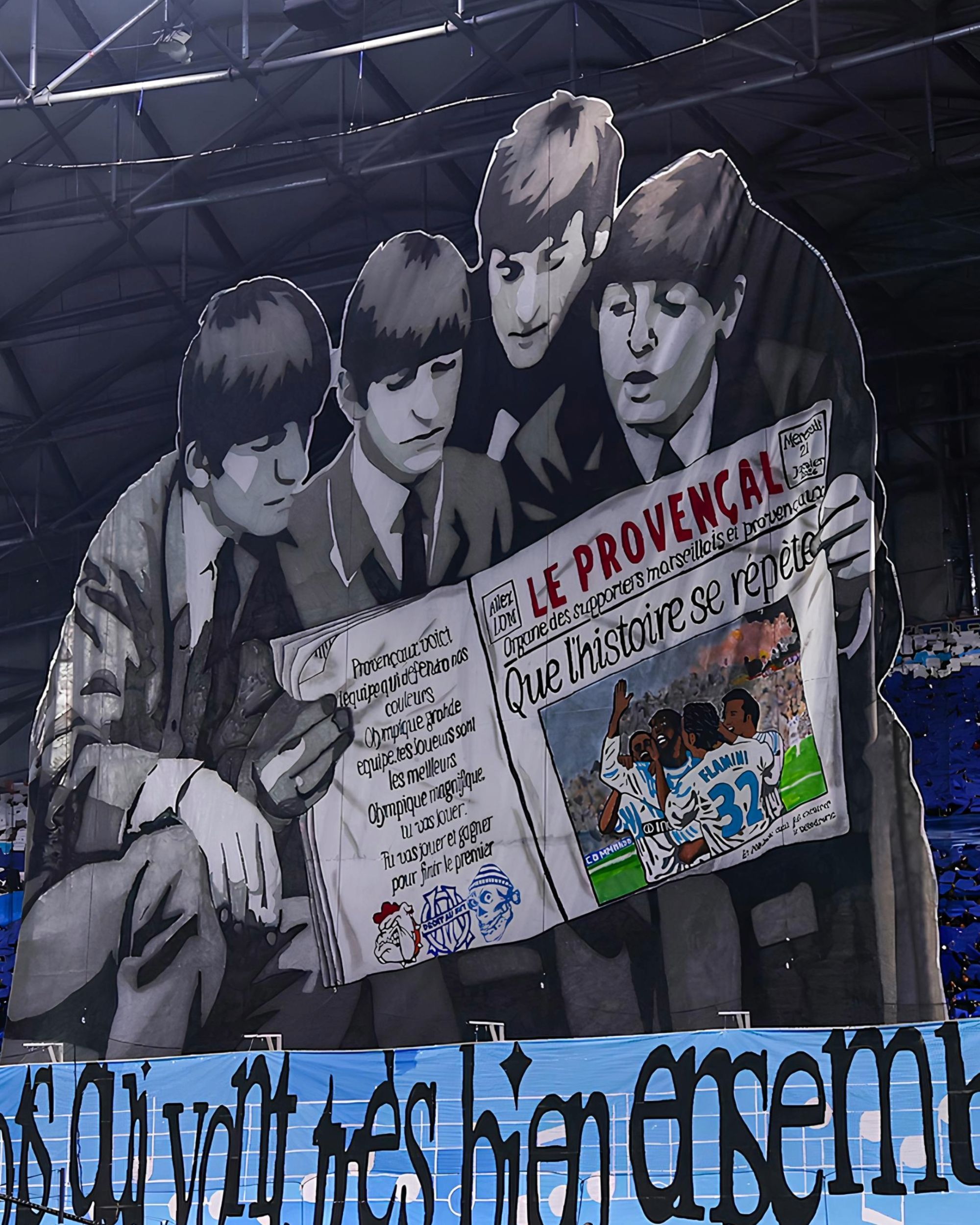

From the Channel to the Bosphorus, the major football federations of the old continent, including UEFA, demand moderation. In England, the only three allowed sponsors on a shirt are on the chest, sleeves, and under the number; Italy allows four slots, but enforces strict size limits, as do Germany, Spain, and France, which allow between two and four. The Austrian case is thus an exception — but changing latitude, the restrictions loosen and vary widely. In Brazil, federal regulations set no limits: Operário PR features nearly twenty logos, Corinthians ten, and Athletico Paranaense switches sponsors and placements depending on the competition. Mexico and Bolivia follow the same freedom, with Pachuca and Querétaro between fourteen and sixteen, and The Strongest and Club Bolívar between fifteen and twenty. Argentina sits in the middle: maximum of ten sponsors allowed, but with possible exceptions. In North America, Major League Soccer takes another approach: a front sponsor, plus the unified Apple TV patch on all sleeves.

Turning eastward, Asia also shows regulatory variety. The ISL in India enforces fairly strict rules with just four slots; in Japan, the J-League sets a limit of five to six ads, while South Korea’s K-League allows up to ten, and Indonesia up to fifteen; on the other hand, the Chinese Super League limits teams to just two to avoid overshadowing state-owned brands. In Oceania, Australia’s A-League mirrors the European model with three controlled logos, while Africa ranges from only a front logo in Ghana to three or four allowed in Egypt, South Africa, Morocco, and Algeria. In short, beyond the context, a single federation directive is enough to determine whether a football shirt remains minimalistic or becomes a kind of advertising billboard. The Hartberg case is simply the most colorful edge of the mosaic.