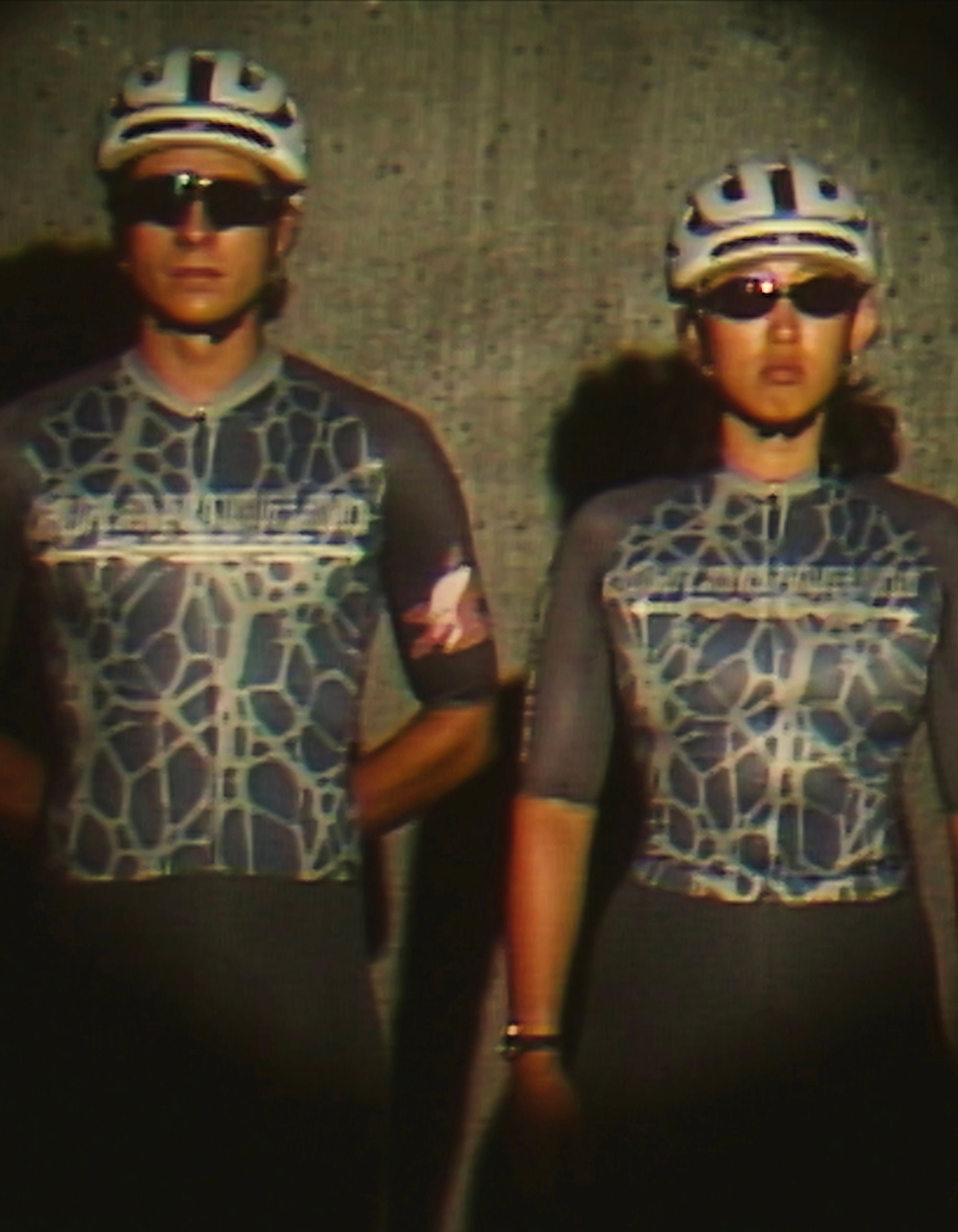

What’s the atmosphere like at a Cycling World Championship in Rwanda? A story from inside Kigali 2025 and some of the most unforgettable moments it offered

If I had to literally answer the question in the title: the air is not good. Because of the pollution levels in Kigali, where I’m writing from, but also because of the thin air at 1,700 meters above sea level. Add to that the humid heat of the start of the rainy season, a city made entirely of hills, cobblestones, climbs and descents (not only for the riders in the race), a course designed by the UCI to crush the riders’ legs and lungs, and you get the scenes of physical annihilation and breathlessness we saw every day after the finish line at the Convention Center.

I know a little about it myself: earlier this week I passed by the basketball court of the Rafiki Club and gave in to the temptation of a three-on-three game with some local kids; after five minutes it felt like I had an NBA Finals series in my legs, and when we finished I could barely recognize my scooter among those parked in front of the playground. So yes, that’s the kind of air you breathe down here—but let’s take the initial question in a broader sense. So, what was the atmosphere like around Kigali 2025, the very unusual Cycling World Championships making its first-ever stop on the African continent?

As already described in this article, the road to the 2025 edition has been long and winding, since the very first day of UCI’s assignment back in 2021. Once you land in Rwanda, however, the endless controversies of the event and the gloomy geopolitical scenarios surrounding it make way—without disappearing completely—for the undeniable charm of this world championship. And so here I am to share with you some moments from my week in Kigali, trying to bridge those five thousand kilometers that separate the 2025 Road World Championships from those who watched from home, in the old continent. A distance hinted at by the spectacular images that came from Kigali these past days, and even clearer for those like me, and many fans, journalists, and international insiders, who experienced on the ground the strangest World Championships ever.

Rwanda or Flanders?

The most anticipated race of the opening weekend, the elite men’s time trial, had one undisputed protagonist: Remco Evenepoel. And more generally, the Belgian fans, as often happens in events like this—even thousands of kilometers and continents away. At the iconic catch-up with Pogacar on the Côte de Kimihurura (the final cobbled ramp), and even more so when Evenepoel crossed the finish line with the best time (by far), the Kigali Convention Center for a moment felt like the heart of Flanders, the home of cycling by definition. Belgian flags, two Flemish riders on the podium (with Ilan Van Wilder taking bronze), the anthem, the chants of “Remco, Remco!”. An evocative scene that reveals the Belgian people’s passion and hunger for big cycling events, momentarily setting aside the political tensions (past and present) that link the two countries.

If Evenepoel crossed the line with three fingers pointed to the sky, reminding everyone that the time trial crown is his for the third consecutive edition, the one left disappointed after day one was his rival, Tadej Pogacar. Time trials are not his specialty, but by now it’s clear that for the Slovenian star, as the saying goes, the sky’s the limit. And so Pogi came to Kigali—on his 27th birthday—with the ambition of pulling off a very tough double. But in the time trial there was no margin for overturning the hierarchy: his opponent’s superiority was manifest. The moment of revenge, however, would come in the most important race of all, yesterday’s road race, where Pogacar reminded the world that he is the best. Of today, and maybe—too soon to say?—beyond our time.

Recon at the Kigali Wall

With the time trial archived, by Monday my thoughts were already on the weekend’s road race. Not to take anything away from the many interesting intermediate races—the U23 and Junior time trials and road races, men’s and women’s—but day one had sparked curiosity about how Pogacar would react. Whether in his natural habitat, on the road and on a course with brutal gradients, he would be able to return the favor to Evenepoel, defending that rainbow jersey he won in Zurich in 2024. And so, after getting a taste in the first days of the Côte de Kimihurura, a section common to all races and categories, on Monday morning I decided to go check out the Kigali Wall (Mur de Kigali), the punishing cobbled climb reserved for the men’s elite. Half a kilometer of uneven pavé, with an average gradient of about 11% and a peak of 18%, widely touted as the most scenic point of the course. And a likely turning point, even though it came a hundred kilometers before the finish.

I reached it with a rented scooter I used to scout the course, the city, its thousand hills, and its lesser- and better-known corners. Along the way I met several riders—chased by young cyclists, kids running alongside, moto-taxis buzzing around, photographers hunting for memorable shots—who were out training in that area. Partly for the altitude, rising at the foot of Mount Kigali, and partly to get a muscle and aerobic feel for what that wall would be like. And it really is as they described leading up to the event: hell on earth. Even on a scooter it was rough—can’t imagine doing it on human energy. There’ll be fun to be had, I thought. There’ll be survival to be found, thought the riders testing the slope.

While I was there, before heading back to town, I also took the chance to figure out where I might position myself on race day (I’ll get back to that), with large crowds expected on the narrow climb. I made it back to the Convention Center just in time for the debut of the women’s U23 time trial, where Italy’s Federica Venturelli won the first medal of Kigali. But it would be at the end of the week, in Friday’s U23 men’s road race, that Italy’s brightest moment at the Worlds would arrive.

“We are the parents of the gold medalist!”

If you’re a cycling fan—or even if you just glanced at the news this weekend—you will have heard about the show put on by Lorenzo Finn. The young star of the Red Bull team confirmed himself, as in Zurich, in the rainbow jersey, an impressive back-to-back for many reasons: for how it came about, in a dominant race that once again gave the impression of witnessing cycling’s and Italian sport’s next big thing; and this despite moving up from Juniors to U23, and being in Kigali the youngest rider in the field, not even nineteen.

Il momento più assurdo della "mia" Kigali:

— Andrea Lamperti (@a__lampe) September 26, 2025

mamma e papà di Lorenzo Finn, fresco di oro mondiale, aspetterebbero il figlio giù dal podio, ma non c'è verso di convincere la sicurezza (compagni di squadra inclusi) che siano i genitori.

Mistero vuole che credano a me, ed eccoci pic.twitter.com/6H5Z1m7MPA

After the finish, Lorenzo had to go through the usual post-race routine: award ceremony, mixed zone, bike check, anti-doping. I moved closer to the stage to soak in some of his joy, but I was intrigued by something happening behind it, out of the cameras’ view. What caught my eye were the domestiques of the Italian team who, instead of enjoying the fruits of excellent teamwork, were apparently arguing with two security guards at an access point to the podium area.

I got closer and discovered the reason for the dispute: outside, behind the barriers, stood Finn’s parents, swearing to the stewards they were indeed the mother and father of the boy who had just won the race, but without a badge to prove it. Even though the riders confirmed it, the guards weren’t convinced. Somehow, and for some mysterious reason (perhaps the fear of looking bad in front of a journalist who might report on the gaffe), my intervention helped get them inside, closer to the podium, where they finally embraced their son. An improbable moment I will remember, and one that reveals something about the strict (not always flexible) organization of Kigali 2025 from a logistical point of view. Traffic blocks, access gates to the Convention Center, daily announcements to residents via text message or WhatsApp, the closing of schools, universities, and offices—all of this turned the week into a smooth-running mechanism, perfectly enjoyable for professionals and fans who came from every corner of the world. Along with the locals, who took advantage of the week off to flock daily to the circuit. In total, according to UCI, about one million people.

The climb to Mount Kigali

Finally, the last day of racing and the most awaited showdown arrived. My plan was clear: when the peloton hit the extra stretch, after the ninth lap of the usual city circuit, I would position myself along the Kigali Wall to witness without a doubt the most spectacular and decisive point of the 2025 Worlds. Getting there by scooter wasn’t easy, far from it: the closure of nearly all the roads linking downtown to Nyamirambo—the neighborhood hosting the cobbled ramp—forced me to ride several kilometers on dirt roads, through poorer, more peripheral areas of the city. A good chance to see that dark side of Kigali the TV cameras steer clear of.

When I got there, I found a massive crowd waiting for the riders. The mix of pathos, the visible fatigue on the athletes’ faces and pedals, the crowd’s excitement, and the deafening noise needed no captions. The images spoke for themselves, as did Tadej Pogacar’s attack, which I watched from the roof of a small house overlooking the road. Exclusively, thanks to the kindness of the owner, who had promised me that incredible spot days earlier, much to the envy of official event photographers.

Alongside Pogacar was Isaac Del Toro from Mexico, trying to follow the Slovenian’s breakaway. His illusion didn’t last long; he cracked after a few kilometers. Nobody could hold Pogi’s pace, not even Evenepoel, who tried to close the gap once the race returned to the city circuit, but it was no use. The best in the world was proving just that, and after about a hundred kilometers solo, he crossed the finish line a minute and a half ahead of the Belgian. On the top step of the podium, under the gaze of President Paul Kagame, stood one of the brightest stars in global sport. With his back-to-back triumph, the curtain fell on a strange, beautiful, and controversial World Championships. The UCI caravan will be back in twelve months in Canada, then in France in 2027, and in Trentino in 2031. They will all be great weeks of cycling, but the uniqueness of the atmosphere here in Rwanda will be impossible to replicate.