How does anti-doping work in cycling? Blood samples, urine tests and logistical challenges

We hear about anti-doping and the agencies that handle it, like ITA (International Testing Agency) and WADA (World Anti-Doping Agency), mostly when the loudest positive cases hit the front pages. Or when scandals, investigations, controversies, or rule and procedure changes in athlete testing erupt. Otherwise it's work carried out away from the spotlight of big events, almost in the shadows — but that doesn't make it any less important or interesting. Even more so in the world of cycling, which for decades has fought a very difficult battle, and where race logistics and timing make the task more demanding than elsewhere. It's often said that doping is ten years ahead of anti-doping, and unfortunately that's not invented: just as in many sports those who attack have a physiological advantage, the same applies in this field, and generally wherever justice, sporting or otherwise, chases wrongdoing.

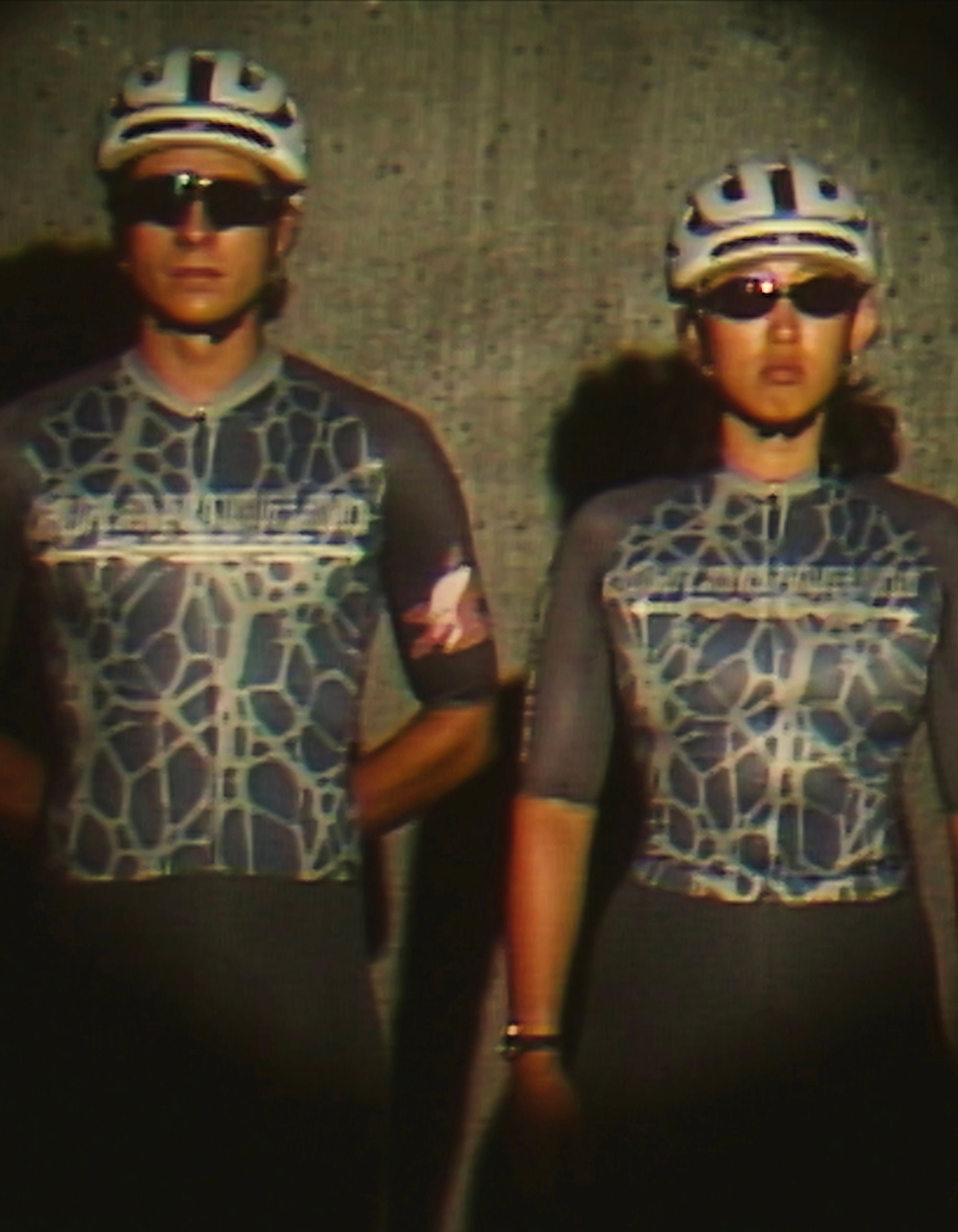

We tried to get a sense of all this on the occasion of Kigali 2025, last month's Cycling World Championships in Rwanda. A unique event for a thousand reasons, which we covered up close and of which today we bring you one final, unpublished angle. After giving voice to the many themes that emerged — Pogacar, Evenepoel and Finn's shows, the atmosphere of the first time in Africa, the many surrounding controversies — this time we took a look behind the scenes to understand how ITA worked on the ground, and more generally how an anti-doping agency operates at major events like this. Thanks to the testimonies of those who coordinated activities on site — Kevin Dessimoz and Leticia De Vega, respectively Testing Operations Manager and Testing Coordinator of the ITA Cycling Department — and with the support of Marta Nawrocka, head of Communications & Media.

Logistics

Kevin Dessimoz and Leticia De Vega work in the ITA's in-competition cluster, with many years of experience in cycling. Last month in Kigali they were the two ITA representatives — the agency operates in nearly 80 sports but has a particular focus on cycling. "In Rwanda we were ten people in total", Dessimoz explains, "Leticia and I, plus six DCO (doping control officers — professionals trained to conduct tests) and two nurses, whom we call BCO (blood collection officers) and who were there mainly to assist with blood draws from athletes' arms. We arrived in Kigali two days before the start of the event. Pre-event testing can be conducted either directly by ITA, or by other national anti-doping organizations or private collection agencies that gather out-of-competition tests at athletes' homes — we take full control when the event starts."

How does the logistics of testing work once on site? "The anti-doping control station was inside the Radisson Hotel, in the Kigali Convention Center, right next to the Media Center," De Vega answers. "Every day there were two or three DCOs in the race finish area, while the rest of the staff were assigned to tests at the riders' hotels. In the control area there are spaces and equipment for testing: a blood sampling room, bathrooms with mirrors and all the necessary equipment. Then there are the chaperones (volunteers), the figures who must notify athletes and who mostly work at the finish line, while the DCOs also go to the hotels. As soon as the athlete is notified, their assigned chaperone cannot lose sight of them for even a moment; they must escort them to the control station as quickly as possible."

Once tests are carried out and samples collected, for the organizational machine the work has only just begun. "We have to ensure that the samples — urine or blood — arrive safely and as quickly as possible at a WADA-accredited laboratory. The point is that in Africa there are few of these, and not all accept every sample or are authorized to perform every analysis. Some blood samples we had to send to Nairobi, Kenya. And the time window is very tight: if we have shipping problems we risk losing the validation of those samples. It's a big challenge — last month there were a couple of occasions when our officers had to personally take a flight to Doha, Qatar, and deliver the samples by hand, in the middle of the night."

Aside from such rapid transfers, ITA staff days in Kigali were still quite busy. Especially for DCOs and BCOs, whose routine starts at 5:30 in the morning for testing riders at the hotels. "The first notifications begin around 6:30–7:00 if it's urine, a little later if it's blood. The goal is to test all assigned riders within about an hour and a half, so as to finish the program by around 9:30 and allow athletes to have breakfast and go out to train. This routine is completed with the day's races and then evening testing windows between 18:30 and 23:00.” These are very intense days for everyone."

Challenges

The World Championships also posed a number of atypical challenges due to the unusual destination chosen by the UCI. While it's true that Rwanda is establishing itself as an African hub for international sporting events, Kigali was still a first-time-ever location, with the resulting unknowns also from an anti-doping perspective. "The main challenge, working for the first time in Africa, was that we could not rely on many local volunteers with a lot of experience. Before leaving we wondered: what experience do they have in anti-doping? How much will we need to train them? Are we sure they will speak adequate English, or at least enough to interact with the riders? Despite the many questions we left with, the answers we received on site were positive."

"In Rwanda there haven't been many big competitions before this World Championships, apart from continental basketball events. It's not comparable to Europe in that respect. In Europe we can rely on experienced staff almost everywhere. The first days were therefore intensive, because most volunteers had no previous anti-doping background and we had to focus a lot, for example, on how to follow an athlete after informing them of the anti-doping control. We wanted to ensure they understood their duties and responsibilities, since they are the athlete's first contact right after the race finish, and it's important to always have a proper and professional first approach."

On the other hand, Kigali 2025's meticulous organization was also more efficient than some recent editions in more conventional venues. "For us it was a pleasant surprise in terms of organization", as it was for many journalists, athletes, industry workers and spectators who reported on the event. "The location of the anti-doping area was very close to the finish, and this made the chaperones' job with the athletes easier. For riders the route was short, both from the finish and from the Media Center, and therefore convenient also for press conferences. Then there are the infrastructures that were made available to us, and many other practical aspects. Overall the feedback is certainly positive for a country that hasn't hosted many international events of this kind yet. Last year in Zurich, by way of comparison, the anti-doping office was further away and was more complicated to reach."

Strategy

The numbers reflect ITA's effort. "In Kigali we tested more than 200 athletes and collected over 280 samples. We collect several types: urine at the finish line or in hotels, and two types of blood, usually always in hotels, in missions we carry out in the morning or in the evening. In total, over 130 urine samples between the finish and hotel missions, about 100 blood samples for the Biological Passport and about 50 serum samples, which are used to analyze different substances and measures". Driving all this is ITA's strategy and mission, which — in addition to a long list of federations — is also a partner of the Olympic Committee and will be on site at the Milano Cortina 2026 Olympic Games. Targeted and cross-cutting. "There's nothing random in our choices". The Cycling World Championships are an ideal showcase to get an idea.

"We are responsible for the anti-doping program in cycling year-round, before, during and after the season. In every sport we work in we perform a risk assessment that considers many aspects: physiological factors, the structure of the sport, internal scientific models we have developed, and all the data we have available. It's a multifactorial exercise, combined with input from other areas. For example, Intelligence & Investigations, the department that investigates and collaborates with reporters to choose the best moments for testing. Especially during major events, however, we always keep a margin of flexibility according to performances. We might see something out of the ordinary or what we would be wrong to call suspicious, but we work on risk. And risk doesn't mean that someone is doping, but that it might be more likely than for others. That's what we call targeted testing, or intelligence-based testing."

In recent months anti-doping has also implemented DBS testing, that is Dried Blood Spots. The method was adopted for the first time in cycling at the Tour de France 2025, and therefore at the Vuelta a España and the World Championships. "It's a less invasive method. There's no vein needle — we collect drops of blood with small finger or arm pricks. To put it simply, you take a drop of blood and put it on a sort of paper where it dries. That means you don't have a liquid blood tube, and the same chain of custody doesn't apply for transporting it to the lab in terms of temperature and time windows. With smaller bulk the transport and storage conditions are more flexible, shipping costs are lower, and all this allows us to collect more samples, to multiply the blood tests we can perform. Also because the sample can be collected immediately after the race — you don't have to wait one or two hours as with other types of draws. This is very useful in cycling, and especially in multi-day races, given the importance of recovery and rest after effort. It's not a method that can completely replace traditional liquid blood samples; it can only be applied for certain specific substances."