FIFA is considering an XXL World Cup That's because 48 teams were not enough

Just the time to breathe after the Club World Cup and the countdown to the 2026 World Cup has already begun. That edition will debut the expanded format with 48 teams, but within FIFA, some are already considering a further expansion. As initially reported by Spanish newspaper As, during a recent FIFA meeting in Zurich, a Council member proposed opening sixteen additional slots for the 2030 World Cup. According to a subsequent report by the New York Times, the proposal came from Ignacio Alonso, president of the Uruguayan Football Federation, who suggested a shift to a format featuring 64 national teams. The idea was preliminarily discussed under the last item, "any other business", on the agenda of the FIFA Council meeting held on March 5. So far, not much has leaked out beyond the scope of the possible expansion, which nonetheless raises several questions.For example, how would the extra spots be distributed—always a contentious issue—and how would qualifications be reshaped, especially in continents with fewer federations, along with the final bracket that would include at least 128 matches, and more broadly, the scale of the event, which would at that point last at least a month and a half.

A FIFA spokesperson confirmed that President Gianni Infantino has agreed to "consider a new proposal", as stipulated by Council regulations, which require examining every internal proposal presented during assembly. "Every idea is a good idea," Infantino later added this past May. Meanwhile, the outlines of the debate are already clear. In other words, the implications for every party involved—directly or indirectly—and the sentiment surrounding the possible expansion. Ignacio Alonso’s idea floats in a sea of tournaments that have grown from L to XL, and then XXL; alongside others just launched, sometimes involving intercontinental travel, saturating the few remaining gaps in the calendar. Much to the dismay—so to speak—of those working in the industry. Be it clubs or national teams, UEFA or FIFA (in this case, a particularly weighty “or”), we now know the scope, logic, and factions in the debate. Matches and travel keep increasing, people keep complaining, and yet each season has a denser calendar than the last. It’s a delicate and unsustainable balance, in which the World Cup only plays a partial role—but as the most important event of all, it is inevitably exposed to the global audience.

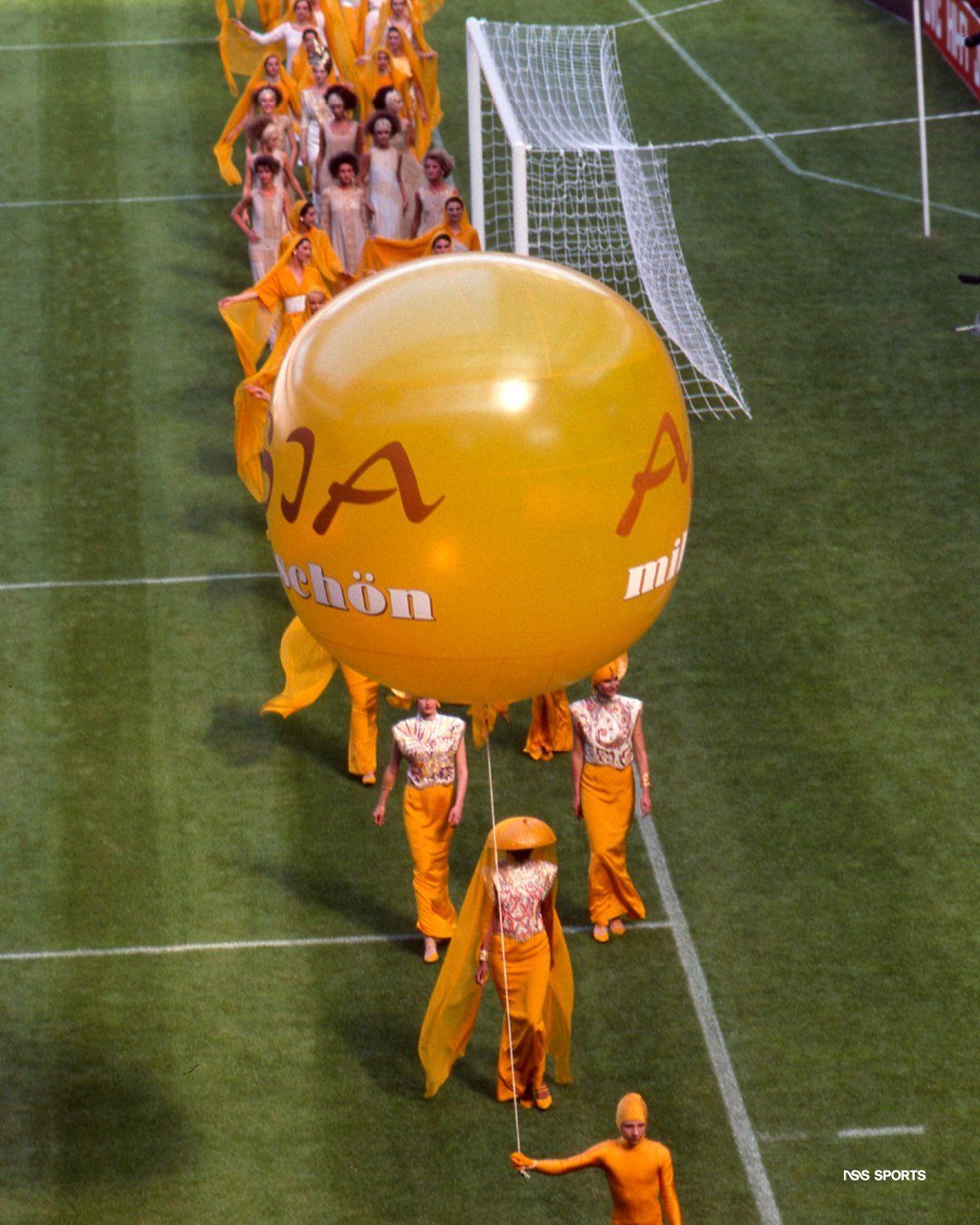

History of the World Cup format

The era of the 16-team World Cup lasted roughly from the tournament’s inception until the 1980s. The next phase, the 24-team format, lasted until France '98, and since then there have been seven editions with 32 participants. If the expansion proposal is accepted, after just one cycle with 48 teams—or in any case, within a short span—it would represent an unprecedented escalation for FIFA’s flagship competition. Let’s not beat around the bush: 64 national teams—nearly a third of those in the world rankings—is truly excessive. Just two and a half years ago in Qatar, the number was half that. And in the tournament's century-long history, the record books show only about 80 different flags—not much more than the 64 proposed for 2030 alone.

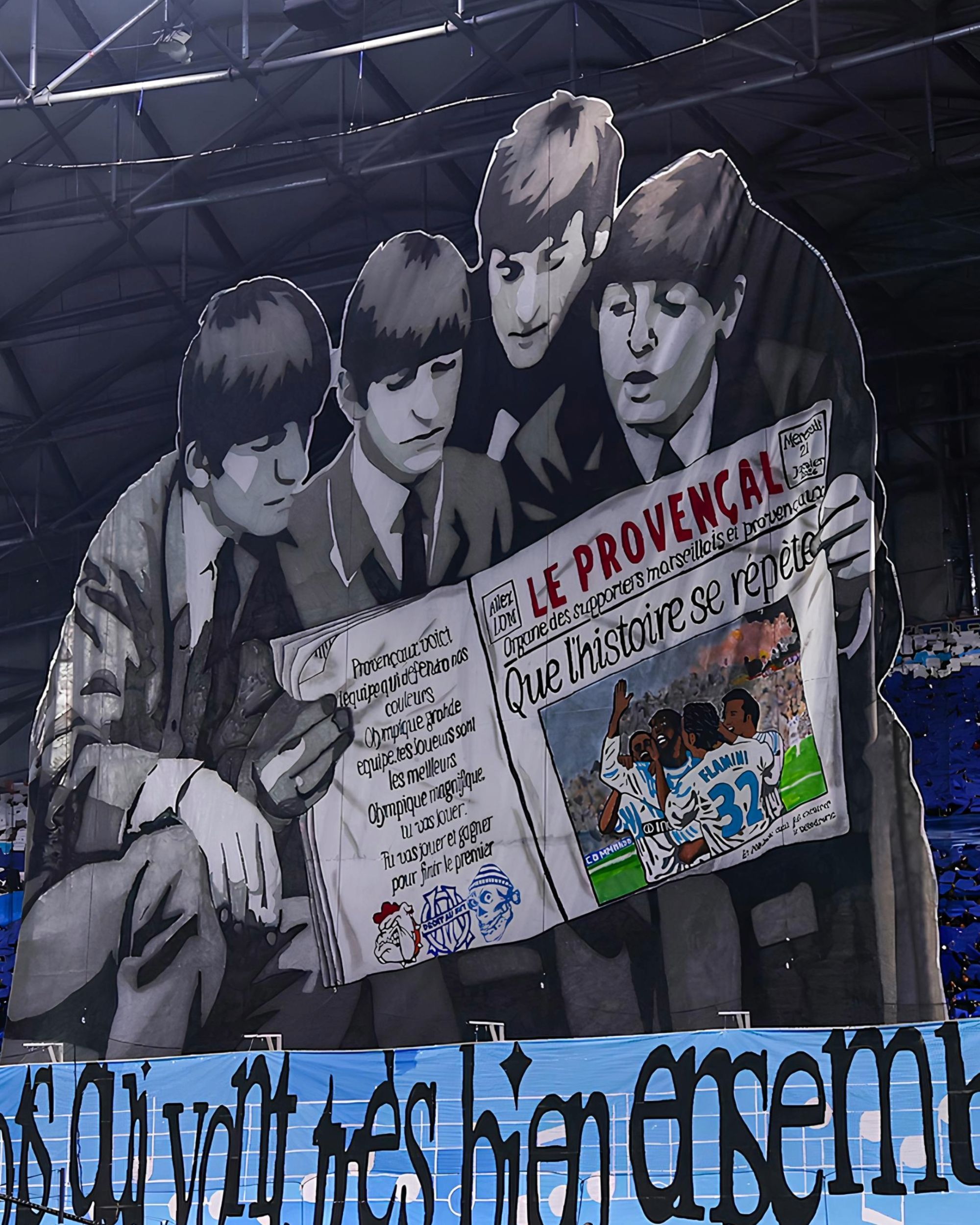

Such a reform would not be shocking to the public, who have grown accustomed—albeit reluctantly—to seeing exclusivity and tradition sacrificed on the altar of revenue. International football calendars—especially for top European clubs that advance deep into multiple competitions, and their stars also involved in national teams—now resemble a year-round reality show. Even the World Cup has shattered tradition: first the winter edition in Qatar, then the 2034 tournament in Saudi Arabia, and in between, the triple-hosted 2026 edition, which will be played in the United States, Canada, and Mexico—during a historically sensitive time. Then the centennial’s traveling show: in 2030 the tournament will span three continents and six countries, starting with a symbolic kickoff in Uruguay, Argentina, and Paraguay, followed by the rest of the tournament in Spain, Portugal, and Morocco. Even the distances have become extra-large.

It’s no surprise that the proposal to include more teams comes from Montevideo, at the heart of the 2030 tournament's organization. The Uruguayan federation clearly has an interest in amplifying the opening phase of the event, and in principle the idea should appeal to Claudio Tapia (Argentina) and Robert Harrison (Paraguay), but not to Alejandro Dominguez, president and representative of CONMEBOL, the South American football confederation. Three or four extra slots would, in fact, leave little to nothing of the regional qualifications for the 2030 World Cup, depriving each federation of 15–20 matches—and related revenue—over the next three and a half years. A shortfall that even FIFA’s generous incentives may struggle to cover.

Pros and cons

The disunity in the Latin football world is just one part of a globally fragmented football scene. The ideological spectrum of the federations is defined, of course, by pros and cons that vary depending on status and geography. On one side, there are the markets on the edges of the empire—namely Asia, Africa, Central America, and Oceania—that would finally gain access to the FIFA World Cup and its resources. On the other, the entire European circus: clubs, UEFA, and human capital including coaches and players, who would face yet another adjustment to the calendar—a month and a half of tournament play involving 1,500 athletes can't be ignored—and therefore an even shorter, more crowded window for their existing obligations. This isn’t new. European federations have long been trapped in a vicious cycle of perpetual growth: revenues, costs, matches, travel distances. And along with it grow the dissatisfaction of professionals and fans, and the gap from a sustainable, acceptable balance. The entire football business model is under pressure, centered around a familiar rift: one side pushing constant expansion, driven by ever-rising operating costs and the need for new profits; the other increasingly struggling to maintain the quality of the game, and facing steadily rising financial demands off the pitch.

Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, a historic figure at Bayern Munich, spoke about this phenomenon in an interview with Italian outlet Corriere della Sera, stating that players and their entourages have "trapped themselves". By demanding ever-higher wages, they’ve forced clubs and federations to seek out new markets. "That money has to come from somewhere, and that’s why more games are played—because of TV market demands. But if players want more money every year and agents want to get paid just to have a chat, what club can still make a profit?". This is the friction point, and the possible clashes over expanding the 2030 World Cup could finally bring all stakeholders to the table in search of a necessary, peaceful, and shared compromise. Because continuing to milk the beast without caring about its insatiable hunger—or the resulting issues (injuries, market saturation, declining appeal, the risk of a lockout)—is not a viable option. At least not in the long term.