How China's stadium diplomacy works in Africa A handbook on soft power ahead of the 2027 Africa Cup of Nations

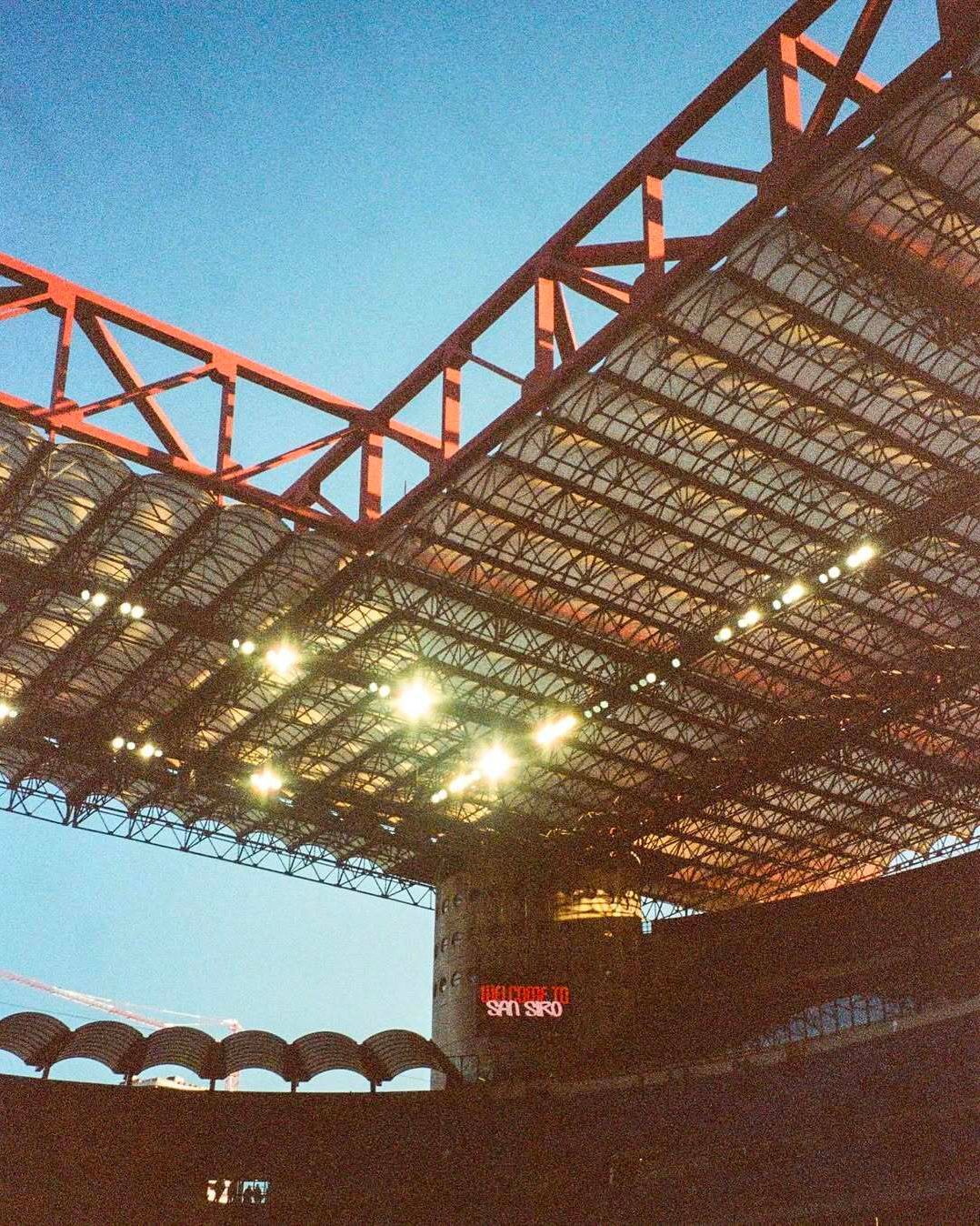

Nairobi, Kenya, 12 August 1987: the final act of the All-Africa Games is set to be played at the Moi International Sports Centre in Kasarani, a brand-new stadium gifted by China. The two teams facing at the football tournament final are Egypt, who would lift the trophy thanks to a 1–0 victory, and the host national team, Kenya, in one of the first major international showcases of Beijing’s stadium diplomacy. "After the match we were told that the Chinese who had built the stadium spent two hours nervously walking around the structure," says James Nandwa, a former Harambee Stars player who was on the pitch that day. "They feared the venue wouldn’t withstand a Kenya goal and the celebration of the 100,000 people in the stands, and perhaps it’s for the best that it didn’t happen."

Almost forty years later, and after two more Chinese financings and a deep refurbishment of the facility, the same Kasarani stadium is once again the center of the continent. It will host at the end of August the final of the African Nations Championship 2024 (CHAN), taking place this summer after a series of postponements, and in a couple of years it will welcome the 2027 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON), awarded to the same three co-hosts: Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. "Pamoja", meaning together in Swahili, and linked by a decidedly red thread: Chinese infrastructural direction.

Made in China

The Confederation of African Football (CAF) is thus, for the first time in history, turning the spotlight on these three East African nations; and with them, on Beijing’s capillary penetration along the shores of Lake Victoria, well documented by the two CAF competitions and the construction sites surrounding them. Almost every stand we are seeing as the backdrop to CHAN 2024, and even more so what we will see with AFCON 2027, bears a Chinese signature: from the aforementioned Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi, for whose restoration a further 13 million dollars was recently allocated, to the stadiums in Kampala in Uganda, and Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar in Tanzania.

The Mandela National Stadium in Namboole, Kampala, was erected in 1997 with a PRC grant of 36 million dollars, and then upgraded fifteen years ago with another government concession from Beijing for 3 million; the latest intervention, completed in 2024, was instead financed with domestic funds and carried out by the engineering brigade of the Ugandan army, the UPDF Engineering Brigade. The Amaan Stadium in Zanzibar testifies to even deeper roots, as the first Chinese stadium project in Africa, built in 1970 and refurbished in 2010. Rounding out the picture is the Benjamin Mkapa Stadium in Dar es Salaam, which costed 56 million dollars and was inaugurated in 2007 under the supervision of the Beijing Construction Engineering Group.

Among the official venues of CHAN 2024, in short, four out of five — the only exception is the Nyayo National Stadium, Kenya — share an Eastern background. And it’s just the tip of the iceberg of a much deeper presence: in sports, with other facilities nearing completion for AFCON 2027, but also in the realm of construction and civil infrastructure, and thus within the framework of the Belt & Road Initiative officially launched by Beijing in 2013.

Eyes on 2027

CHAN is therefore serving as a general test, but the real proving ground lies in the construction sites that must be completed by 2026. In Nairobi, the Talanta Sports City is moving at a brisk pace: 60,000 seats, contract awarded to China Road & Bridge Corp, delivery announced for the end of the year, and status as the main venue for ceremonies and headline matches. It is the flagship project of the new season of stadium diplomacy in East Africa, and it is the one that more than any other will show whether the timeline aligns with the deadlines required by CAF. In Tanzania the balance instead tips toward Arusha, a new 60,000-seat venue with a budget around 120 million dollars, while in Dodoma work is underway on a smaller stadium to complete the mosaic. In Uganda, finally, there are two projects in progress, in Lira and Hoima, with Egyptian and Turkish direction.

The technical perimeter is set by CAF: for AFCON, three stadiums are required for each host, with one arena of at least 40,000 seats and two of 20,000, as well as a media center, TV compounds, VAR stations, and training fields for each national team. It is also a matter of geography: the facilities must be centered around an international airport and adequate hotel capacity, which is why the Ugandan government — presided over by Yoweri Museveni since 1986 — chose Hoima, a few kilometers from the new Kabaale International Airport. All this concerns football and its surroundings, but as anticipated the discussion does not end here — quite the opposite. Stadiums host the matches and provide the most eye-catching postcards, but it is the infrastructure that makes it possible to bid for tournaments of this scale.

Beijing’s Shadow

In Entebbe, the upgrade of Uganda’s international airport was financed by Exim Bank of China loans and carried out by CCCC (China Communications Construction Company). AFCON delegations and industry personnel will land here, before moving toward the capital along the Kampala–Entebbe Expressway, also made possible by Exim financing. And then there are dams and hydroelectric plants at Karuma and Isimba, new telecommunications infrastructure such as the e-Government Infrastructure and Huawei’s Safe City surveillance program, and also hospitals like the China–Uganda Friendship Hospital in Kampala as well as industrial zones such as the Liao Shen Industrial Park and the Sino–Uganda Mbale Industrial Park. A universe of works made in China that could soon also include the new EACOP pipeline, a pipeline linking Uganda and Tanzania.

Likewise in Kenya, the railway from Mombasa to Nairobi, built by China Road and Bridge Corp, is the backbone of internal transport between the coastal area and the hinterland; to which is added the long list of road works such as the Nairobi Expressway and Thika Superhighway, port projects such as those in Lamu and Mombasa, energy projects such as Garissa Solar, healthcare (Kenyatta Hospital, Mama Lucy Kibaki) and digital projects (Konza Data Center). And further south, beyond the Tanzanian border, Beijing’s shadow can be seen almost everywhere: Dar es Salaam has started the port upgrade with Chinese contracts; the historic TAZARA between Tanzania and Zambia is being relaunched with a thirty-year concession and CCECC (China Civil Engineering Construction Corp) investments; the Mtwara–Dar gas pipeline (Exim financing, Chinese firms) feeds the coastal belt; in Zanzibar the new Terminal 3 of the airport has entered service, financed and built by Chinese companies; and the national digital backbone continues to expand with Huawei contracts. So many works — and who knows how many more to come — along the same route connecting China, Africa, and other regions of the world: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The new Silk Road

Chinese industry arrived on the continent well before the West, and with much stronger guarantees. Today, after decades of investment, its hegemony is almost unapproachable. Between 2000 and 2023 Beijing signed in Africa over 1,300 deals worth more than 180 billion dollars; of these, in just the last decade Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania absorbed over 7 billion across railways, ports, energy, airports and, to a lesser extent, stadiums. The framework is the new Silk Road: not charity, but a strategy that buys credit, secures diplomatic and political assets in international fora, access to resources, export outlets, and an inexhaustible source of contracts for state industry.

In this landscape, stadiums weigh relatively little in the accounts, but a great deal in the collective imagination — which is why over the decades the eloquent expression stadium diplomacy has taken shape. The logic for preparing major sporting events, after all, is simple: those who can deliver on time and at manageable costs are in charge. A pattern that Beijing has shown it can now embrace, supporting programs such as Kenya Vision 2030, Uganda Vision 2040, and Tanzania Development Vision 2050, which use tournaments as accelerators for development.

@nsssports Il #Camerun veste italiano: quale maglia storica vi viene in mente? #nsssports #sportstiktok #footballtiktok #footballjerseys #AFCON Redrum Savage 21 HuizarDj Intrumental Remake - HuizarDj

This is a global and long-standing dynamic, as a few examples from other parts of the world remind us: Ebimpé in Abidjan in Ivory Coast for AFCON 2023, the twin stadiums of Bata and Malabo in Guinea for AFCON 2012 and 2015, the Estadio Nacional in San José in Costa Rica, the Morodok Techo in Phnom Penh in Cambodia — and the list could go on. In Africa, however, stadium diplomacy is sharper than elsewhere because it dovetails with urgent infrastructural needs and with governments that, in addition to image and consensus returns, seek fast partners who are not overly attentive to democratic and social standards.

Interpretations of these processes are multiple. NGOs and human rights observers call for transparency, sustainable maintenance, and social safeguards on construction sites; Western capitals accuse Beijing of having created a system of dependency and of pursuing neo-colonialist policies, but they rarely offer valid alternatives; Beijing, for its part, offers integrated packages (design, finance, and construction) and quietly cashes in its political, diplomatic, and commercial return. In the case of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, if deliveries keep to the schedule, AFCON 2027 will offer the postcard China desires: visible, functioning infrastructure, useful well beyond the tournament. And this is where the CAF competitions stop being just sport and become a vade mecum of soft power.