The strangest stadiums in UEFA playoffs Unconventional facilities and remote destinations

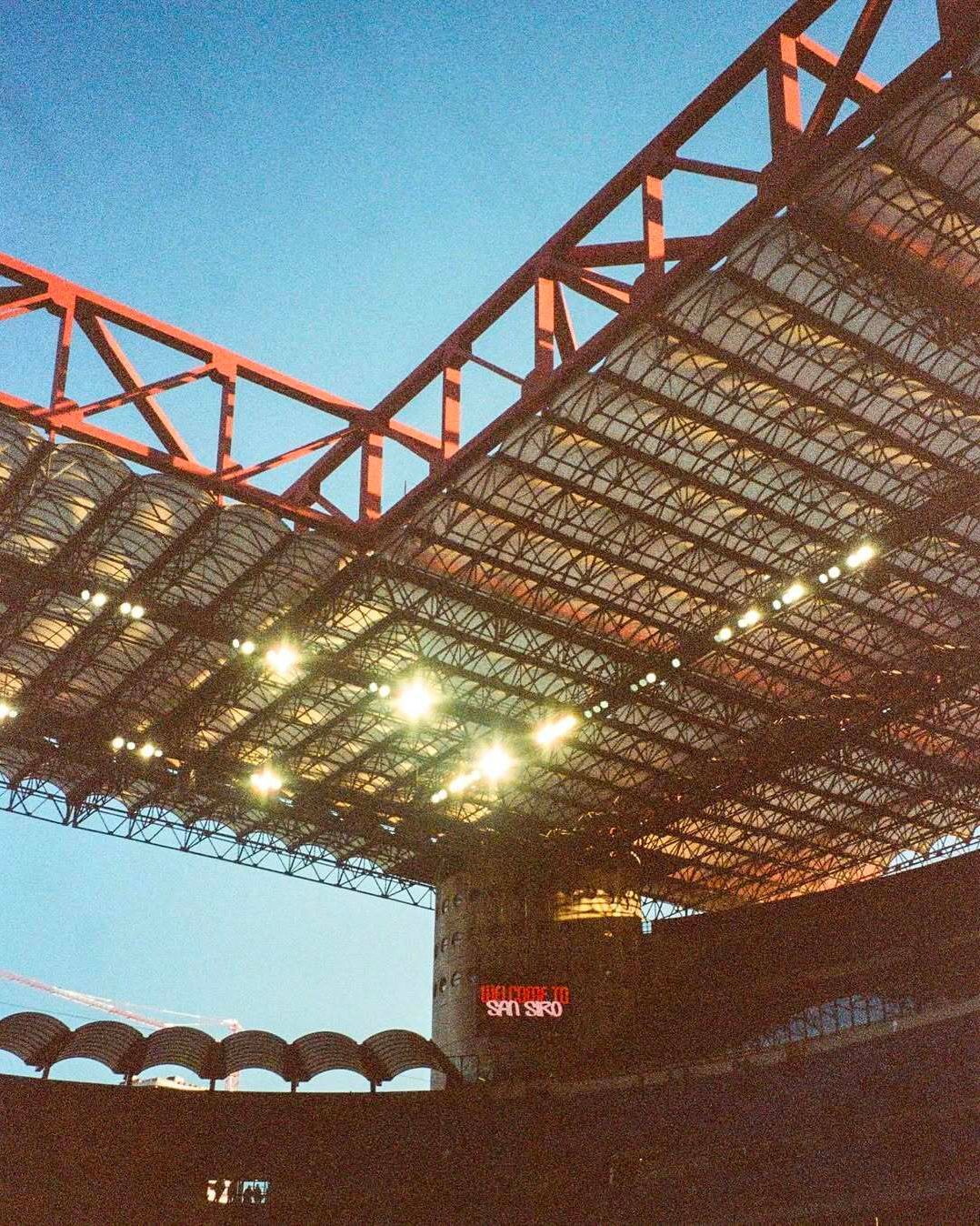

Where European maps now reach, the UEFA flag does too. If not beyond, as the Europa League and Conference League qualifiers of these weeks are reminding us once again. The expansion of the continent’s football geography, driven by Nyon and coming into full swing in 2021 with the introduction of the third competition and with the universal 36-team format introduced in 2024, is now well documented and headed in a rather clear direction. To include more and more markets, open up channels and commercial outlets, and bring UEFA anthems to every latitude.

The design is reflected not only in macro-structural novelties but also in the criteria and the capillarity with which teams gain access to qualifying. In the current playoffs we are seeing several realities that once would have seemed unusual on UEFA stages, and that instead have just clinched a berth, or are close to it, for the 2025/26 mega-groups. Teams never seen on the international stage, long away trips full of complications, sometimes in evocative and seemingly little-European settings, much to the chagrin of those who, in the name of technical level and the show on offer, call for restoring the exclusivity of the competitions.

Different kind of stadiums

We begin at the Strait of Gibraltar, where football is literally played in the shadow of the Rock and a stone’s throw from the airport runway. The Lincoln Red Imps are already guaranteed a spot in the next Conference League, and their case has gone viral. The Victoria Stadium—a postcard with aircraft tails in the background—is under renovation, and in the meantime the club alternates between Europa Point—a gem for lovers of scenic grounds, set between sea and headland—and the Portuguese venue Estádio Algarve for the biggest nights. In short, three different sets in a single season: where else do you find another team with such an itinerant and photogenic domestic life?

In the heart of the Balkans, meanwhile, the UEFA caravan will stop in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Pod Bijelim Brijegom, literally “Stadium under the White Hill,” is not just a poetic name but a caption: the main stand of the ground rests against a hillside of white rock, while the ends are open, with green spaces behind the goals. A kind of landscape amphitheater where the atmosphere in the stands tends to heat up easily. Aesthetically some compare it to the famous stadium of Braga, a direct opponent in the playoffs and by now an old acquaintance of the Europa League. For those who don’t know it yet, Estádio Municipal is a work of art carved into a granite quarry and signed by a Pritzker winner, with two parallel stands, the rock as a natural terrace, and the idea that landscape and architecture are one and the same.

Winter is coming

In recent years Scandinavia and its neighbors have stopped being summer exotica: these are leagues that produce more and more talent, scout well, and go deep in international tournaments. In any case, they remain hellish away trips for climate, kickoff times, and distances. Iceland is the most extreme example, with Breiðablik ninety minutes away from qualification after beating Virtus San Marino 2–1 in the first leg of the Conference playoffs. Reykjavík at the end of August is already in autumn mode, with its artificial pitches, wind that perpetually cuts to the bone, and temperatures already quite fresh. A preview of the winter months—icy and snowy—with evenings when the “edge of the world” feeling makes every away day a lottery.

Further east, in the maze of Finnish lakes, lies Kuopio. Thanks to the playoff mechanisms, KuPS has at least a place in the league phase in its pocket, with the Väre Areena (4,800 seats) ready to welcome the UEFA anthem on its turf for the first time. Artificial, of course, surrounded by trees, meadows, and silence. It’s the typical away trip that scrambles continental habits: connecting routes, changing light, temperature swings. Not as remote as Iceland or the Faroe Islands, but for clubs from Mediterranean Europe it’s already North with a capital N.

And then there’s the beacon that taught everyone to take the north seriously, Bodø/Glimt, a semifinalist in last season’s Europa League. Aspmyra Stadion, with its office blocks as ends and the inevitably artificial surface, stands above the Arctic Circle, where the wind is unavoidable as well as icy, the daylight keeps its own rhythm, and snow can fall well into spring. That’s also why, on off-season Arctic nights, we’ve seen big teams collapse—both Rome clubs, for example, with the 6–1 handed to AS Roma a few years ago and last April’s quarter-final against Lazio.

All around, the picture is rich: Bergen’s Brann (Norway) is on the rise, alongside the historic Rosenborg and Fredrikstad; likewise Sweden’s Malmö FF is by now a familiar UEFA presence, this year joined by Häcken. These aren’t improbable leagues, but ecosystems on the up. Watch any Nordic match in late October, though, and you’ll immediately understand why many managers—quite apart from the level of the opposition—prefer trips closer to home.

Eurasia and off-course destinations

UEFA’s East is more a cultural concept than a cartographic one, and in recent years it has become routine. The first example that intertwines football, history, and geography is Qarabağ, a club from Ağdam (Azerbaijan) that plays in Baku and has for years sailed steadily through the major competitions of the Old Continent. Its European nights unfold on the Caspian, in venues reached by opponents after trips of over ten hours and two flight connections.

Further south, the eastern Mediterranean keeps serving up new stories. Paphos (Cyprus) is making its high-level European debut and has already poked its nose into the Champions playoffs; its home games are played at Limassol’s modern Alphamega, for UEFA standards reasons. It’s a recurring theme: in Luxembourg, Differdange 03 looks after a gem like the old Thillenberg, a ground with a wooden stand and old-world charm, but for Europe it has to use the Stade Municipal. In any case, a surprising novelty. Then there are cases where playing elsewhere, on neutral ground, is mandatory. Belarus, by UEFA decision, cannot host matches, so Neman Grodno plays in Hungary in Szeged, and behind closed doors. Likewise, Ukraine continues to live a sporting exile, with Shakhtar Donetsk making Poland and Kraków its European home. The Mediterranean, finally, awaits a small, huge surprise: Ħamrun of Malta. The Spartans are in the hunt for a historic first league phase for the country, just as Virtus dreams of writing the same page for San Marino. For both federations, a single visit to UEFA group stages is worth a decade of slow growth.

This is the new normal: UEFA making itself seen in every periphery of its empire, in stadiums that look designed by AI, with airports on the touchline, expeditions into prohibitive time zones and climates, and midweek trips at the limits of sustainability. To some it seems like an excess of globalization or commercialization of the product, but certainly not to those who love different stories. Because the wider the map grows, the more the angles multiply from which to watch football, and every so often, to explain a match, it’s nice to start from the weather, from a stand that emerges from a hillside, or from other factors usually alien to top-level football.