The complete list of Winter Olympic mascots From Grenoble 1968 to Milano Cortina 2026

As the opening of Milano Cortina 2026 draws closer, excitement continues to build around the event set to take place from 6 to 22 February. First inaugurated in Chamonix in 1924, the Winter Olympic Games possess a unique kind of magic, thanks to the breathtaking mountain landscapes and snow-covered peaks that host the competitions. Every four years, the selected ski resorts dress up for a few weeks in the global spotlight, enjoying a moment of international glory. For this reason, promotion plays a crucial role, relying on several key elements to enhance the event’s success. Among them is the creation of one or more official mascots. As an integral part of the Games’ brand identity, these commercial symbols—often depicted as animals or anthropomorphic figures—become the most immediate association with a specific Olympic edition. Conceived as carriers of Olympic values and closely tied to the host territory, mascots go on to become merchandise, animated characters and cultural icons, permeating every aspect of the event.

The first Winter Olympics mascots

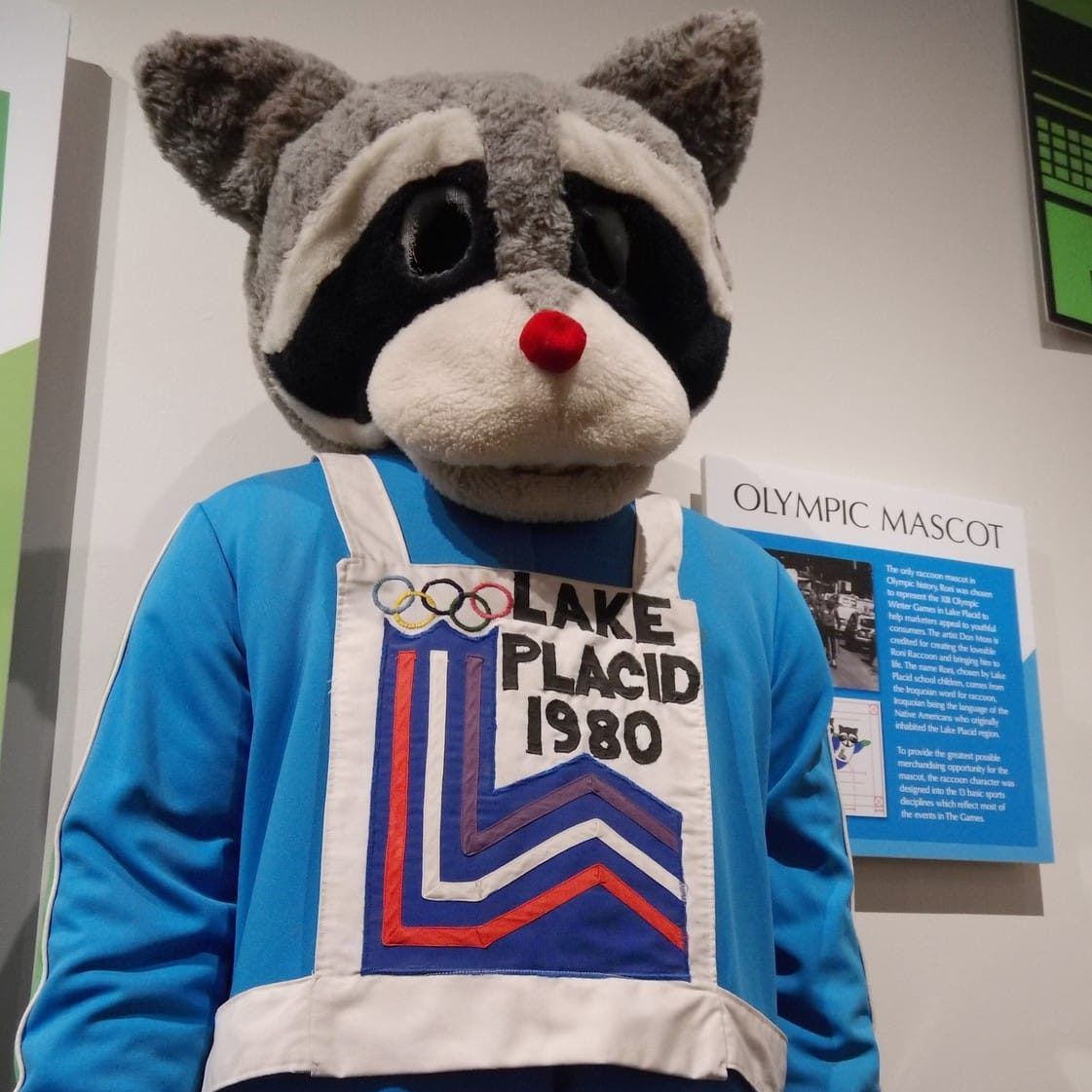

The first mascot of the Winter Olympic Games—though at the time it was simply referred to as a character—was a little figure with a red-and-white head and a zigzagging blue body, designed by Aline Lafargue. Its name was Schuss, a German term referring to a straight, high-speed ski descent, and it marked the beginning of a tradition that has remained unbroken since Grenoble 1968. Strictly speaking, the following edition in Sapporo in 1972 did feature a mascot, but it was unofficial, as it was not recognised by the Olympic Committee. This was Takuchan, a Tibetan bear skiing with a green scarf and hat, created by the design department of Seiko, one of the Games’ sponsors. For Innsbruck 1976, Schneemandl was introduced—a snowman wearing a red Tyrolean hat that proved hugely popular. Alongside him was a secondary mascot named Sonnenweiberl, meaning “sun woman” in Austrian dialect. Four years later, at Lake Placid, the spotlight fell on Roni, a raccoon dressed in a light-blue ski suit with red gloves and boots. His name derives from the term used for the animal in the Iroquois dialect, native to New York State. The choice was a natural one, as the raccoon is a symbol of the Adirondack Mountains.

Iconic mascots from the 1980s to the 2000s

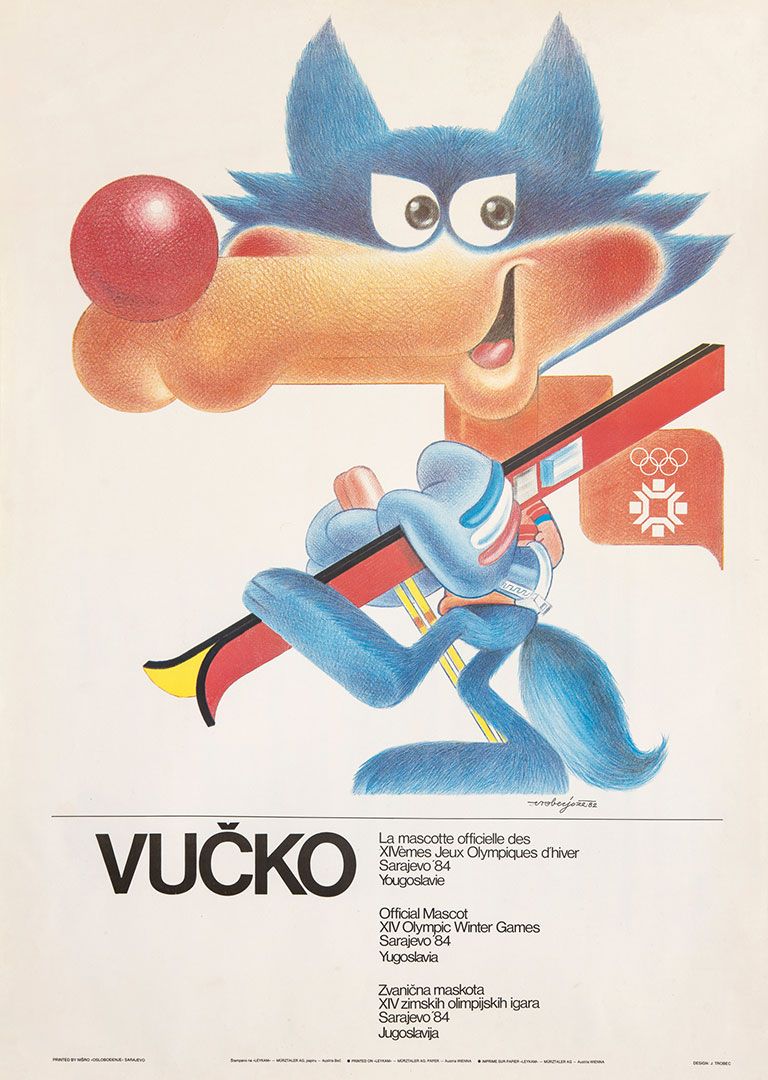

At Sarajevo 1984—an edition that saw Italy return to Olympic gold after eight years—the mascot was Vučko, a black-furred wolf from the Dinaric Alps. These Olympic Games played a significant role in softening the image of the wolf, an animal often portrayed negatively in Balkan folklore. The first true pair of mascots appeared at Calgary 1988, inaugurating a trend that would be repeated many times thereafter. The siblings Hidy and Howdy, also known as the Welcome Bears, took their names from the phrases “hi” and “how do you do”, symbols of the hospitality typical of Calgary and Canada more broadly. The pair enjoyed extraordinary commercial success during the dream Olympics of Alberto Tomba. Albertville 1992, by contrast, belonged to Magique, the first non-animal mascot and one of the most cryptic and complex ever created. It was a stylised child shaped like a star, symbolising dreams and imagination, with arms and legs extending from a cubic torso. Dressed in blue and wearing a pointed red hat, Magique replaced the original mascot concept, which had been a chamois. This edition also marked the first appearance of an official Winter Paralympic mascot: Alpy, a one-skied mountain peak representing the Grande Motte.

Just two years later, the XVII Winter Olympics were held in Lillehammer. For the first time, the Winter Olympics were staged in a different year from the Summer Games, establishing the alternating two-year cycle that continues today. The mascots were Håkon and Kristin, two blond children dressed in Viking attire and inspired by historical medieval figures: King Håkon of Norway, who reigned from 1217 to 1263, and his aunt Kristin, a princess who married the leader of a rival tribe to restore peace in a divided nation. Accompanying them was Sondre, a troll with an amputated leg and a single ski, the Paralympic mascot. In 1998, at the Japanese Olympics in Nagano, the spotlight shifted to a quartet of snowy owls known as the “Snowlets”. Sukki, Nokki, Lekki and Tsukki featured almost childlike designs, bright colours, and each represented one of the four natural elements. Alongside these symbols of wisdom—traditionally associated with the Greek goddess Athena—there was also Parabbit, a white rabbit with green and red ears.

From mythology to modern design

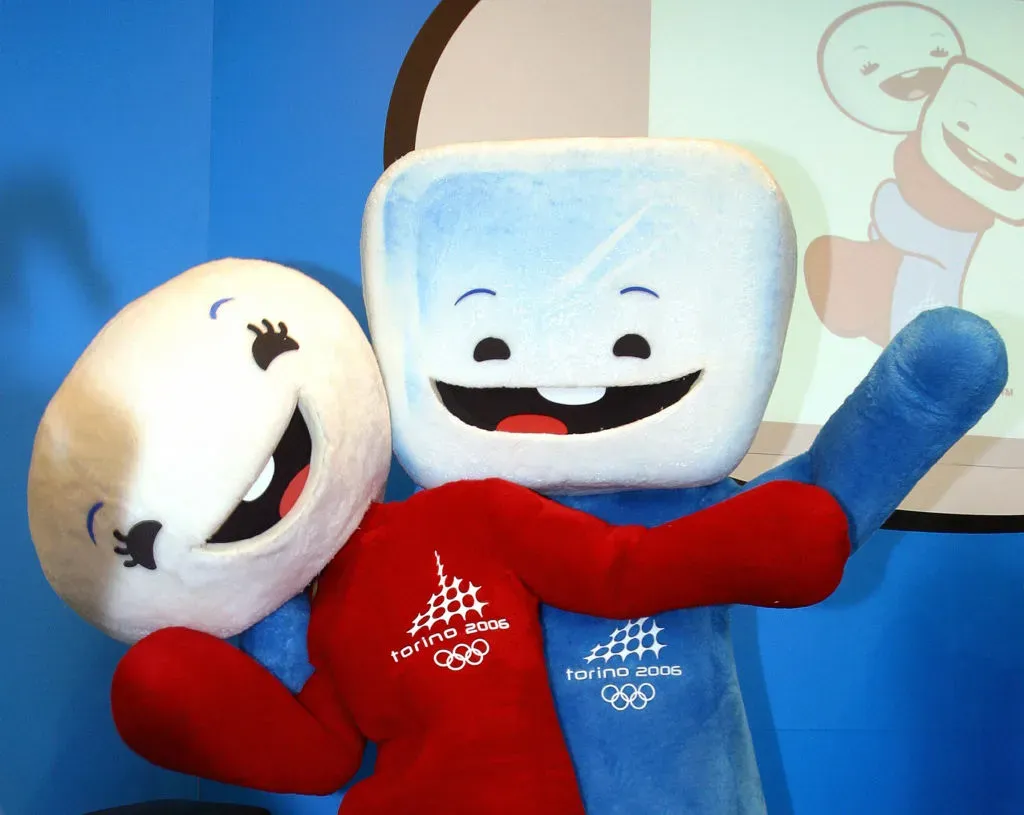

Salt Lake City 2002 was represented by a trio of animals deeply connected to Utah and its origins. Powder, a white hare, Copper, a beige-furred coyote, and Coal, a brown bear, reflected the region’s wildlife and natural resources through their names. Each wore a necklace featuring a stylised animal inspired by the rock carvings of the area’s ancient peoples. Otto the sea otter joined them as the Paralympic mascot. In 2006, the Winter Olympics returned to Italy in grand style. The successful Turin Games were symbolised by an unconventional duo: Neve and Gliz, a snowball and a cube of ice with human features. The two characters even starred in a 52-episode Rai animated series leading up to the Games, and their statues stood for nearly twenty years in a park in the Mirafiori Sud district. A snowflake aptly named Fiocco completed the picture for the Paralympics.

At Vancouver 2010, the mascots were Quatchi and Miga, two mythical animal-like creatures from ancient local legends. Quatchi is a sasquatch living in the forest, endearingly portrayed with blue earmuffs and thick fur. Miga, meanwhile, is a sea bear—a hybrid between an orca and a Kermode bear. Unexpected popularity, however, was claimed by Mukmuk, sidekick to the Paralympic mascot Sumi, a rare native marmot. The mascots of Sochi 2014 were instead left without individual names: a trio consisting of a hare, a polar bear and a leopard. Their selection sparked controversy, as it was widely believed to have been politically influenced, to the detriment of other designs that had garnered greater public support. Alongside the Paralympic symbols—a snowflake and a sunbeam, previously seen in other editions—the trio appeared on the 25-ruble commemorative coin introduced in Russia in 2012.

Tina and Milo: the mascots of Milano Cortina 2026

The year 2018 belonged to the South Korean Olympics in PyeongChang and the white tiger Soohorang. “Sooho” means protection, while “rang” is the central part of the Korean word for tiger—an animal considered a sacred guardian of the nation. Bandabi, a dark-furred Asiatic black bear, served as the Paralympic symbol. Four years later came Beijing 2022, which introduced cartoon-style mascots rich in symbolic meaning. Bing Dwen Dwen is a giant panda wearing a shell of ice: “bing” means ice in Mandarin, while “dwen dwen” conveys strength and vitality. Alongside him is the anthropomorphic lantern Shuey Rhon Rhon, red in keeping with tradition and wrapped in a golden scarf. Finally come the newcomers Tina and Milo, set to make their debut at the upcoming Milano Cortina Olympics and unveiled on the stage of the Sanremo Music Festival last February. They represent two stoats—one female with light fur and one male with dark fur and a missing leg—and can be considered the first truly Gen Z mascots. Joining them are six snowdrop flowers named Flo, which together with Tina and Milo form part of a broader narrative that will increasingly unfold during these eagerly anticipated weeks.