How can GPS tracking improve the safety of cyclists? The protection of riders is set to enter a new phase at the 2025 UCI World Championships

With the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia in the books, and the Vuelta a España that started this past weekend, cycling’s summer is entering its final sprint toward the UCI Road World Championships 2025. The 98th edition of the World Championships, scheduled from 21 to 28 September, will be unlike any before it. For several reasons—but first and foremost the venue: it will be raced in Kigali, Rwanda—the absolute debut of top-tier cycling on African soil, and a unique milestone in the sporting history of the sub-Saharan region and, in particular, the Great Lakes Region.

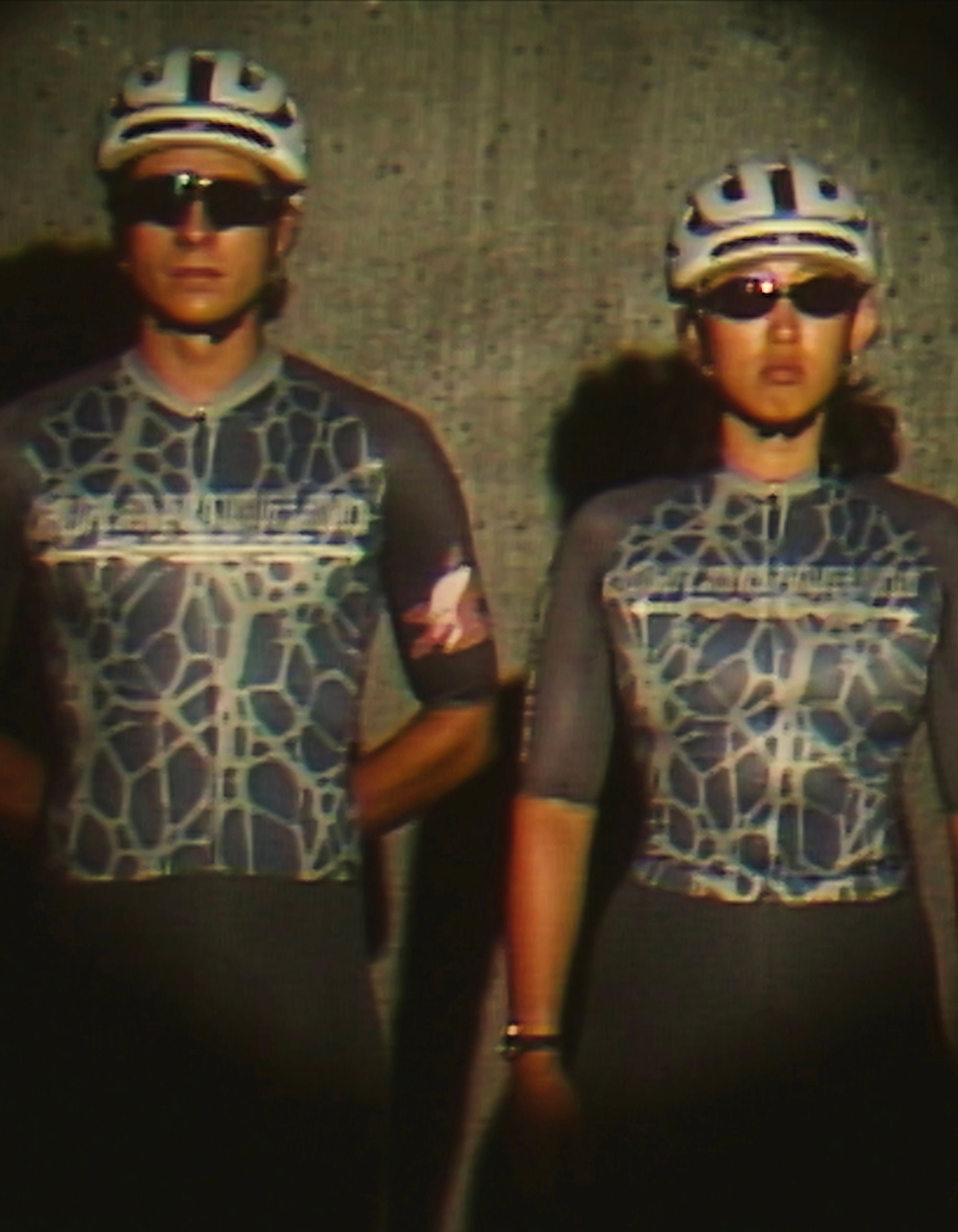

The curiosity, however, is not just geographic. There’s a regulatory, technological, and rider-safety issue that has animated insiders in recent months, and it will come back into the spotlight right before the Worlds: the introduction of a GPS tracking system, used for the first time on a large scale at Kigali 2025. The UCI has long announced its decision to make it mandatory to apply this small device on all bikes and across all categories: men’s and women’s, elite and junior. The idea is that full traceability of movements on the course can optimize emergency response in the event of crashes: one of the most concrete answers, so far at least, to the growing call for cyclist protection.

Context

The push, unfortunately, has been fueled by two recent tragedies: the death of Gino Mäder at the 2023 Tour de Suisse, and a year later that of Swiss junior Muriel Furrer during the 2024 Zurich World Championships. In the second case, after twelve months of investigations the dynamics are still shrouded in mystery, as are the exact location and moment of the crash that led to the young Swiss rider’s death. The time it took to locate and assist the athlete, however, raised a series of concerns—stronger than ever—about the use of technology to prevent such episodes in professional cycling. “In hindsight,” acknowledged race director Olivier Senn, “a GPS system would have been a perfect solution, with which Furrer could have been found and assisted more quickly.”

Despite these premises, as we’ll see, trials of the tool have created friction between teams and the federation. Not so much over the principle of tracking athletes—which addresses a priority shared by all parties—but over methods, responsibilities, and data management. And, in Rwanda’s case, over reliability in the local digital context, despite assurances provided by the organizers.

GPS tracking system

The safety GPS the UCI is introducing is a small 63-gram tracker supplied by Swiss Timing and mounted on the bike frame. Its task is to detect at every moment where the athlete is and to trigger automatic alerts in case of anomalies—situations in which an immediate emergency response might be necessary. The real-time position feeds into a control room shared by race direction, medical services, and commissaires, with the goal of shortening the time needed to locate and intervene in the event of an incident.

The system works on three levels: data capture of coordinates and speed, transmission via a continuous uplink, and analysis of the data. This is where the alert rules come in: if a bike remains stationary for 30 seconds, leaves the course trace, or records abnormal speed variations, the control room initiates a verification protocol. Based on the trials conducted so far, the control room then cross-checks GPS data with TV images and weather to decide how to deploy medical staff and vehicles. From a regulatory standpoint, the UCI clarifies that this is a strictly safety use—nothing to do with performance, tactics, or TV broadcasters. It is the missing technological piece, loudly requested over the past twenty-four months: a beacon that’s always on for every bike, designed to avoid losing precious minutes when they matter most.

The 2025 UCI World Championships

After being the stage for the tragic deaths of Mäder and Furrer, Switzerland served as a testing ground for GPS. At the 2025 Tour de Suisse, the organizers opted for an extended test, with trackers on all bikes and on the convoy, plus a dedicated Safety Command Center. In practice, it was the first full application of the model, observed with interest by other organizers and welcomed by the UCI as a valuable case study ahead of Kigali.

The approach was different at last week’s Tour de Romandie Féminin, where the test was UCI-driven—thus within the SafeR framework—and limited to one athlete per team, to refine software and protocols before the Worlds. The choice, however, sparked a clash on the eve of the race: five teams did not designate their rider and were excluded from the start, while the UCI called the non-cooperation deplorable and reminded everyone that the device, weighing just 63 grams, would be mandatory for all in Kigali. The teams clarified in a joint statement that their objection concerns the process adopted by the federation: the choice to apply GPS to only one bike, the timing of the request, data governance (who manages it, for how long, and with what guarantees?), and responsibilities in case of malfunction. In the background is Velon, a company close to the excluded teams, which has been developing live-data systems and on-bike cameras for years—making the issue of “who sets the standard and controls the data flows” a sensitive one.

Beyond GPS

GPS is not the solution; it is one solution. The UCI has placed it within a broader framework, called SafeR, which aims to reduce peak speeds, simplify in-race decision-making, and shorten response times. Numbers collected in the first half of 2025, across almost 300 analyzed incidents, indicate that the most frequent cause remains rider error; next come mass sprints, cobbles, descents, and wet asphalt. Hence some practical measures: the 3″ rule in sprints, the extension of the 3 km rule to 5 km, a Restart Protocol for neutralizations and restarts, and convoy management with dedicated corridors to limit overtaking. On the equipment front, from 2026 there will be new wider handlebars, rims with a maximum height, and forks with limited internal widths, while in October at the Tour of Guangxi a maximum gear ratio will be tested to level off speed peaks in critical contexts.

Safety is not only about crashes and vehicles—it is also about health and prevention. In women’s cycling—but not only—there is growing attention to RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport), a condition due to chronically low energy availability that alters hormonal and metabolic functions and increases the risk of stress fractures, amenorrhea and menstrual irregularities, decreased bone density, infections, and performance decline. In 2023 the IOC encouraged the use of REDs CAT2, a tool that helps doctors and staff catch cases early, setting recommendations and possible restrictions on training and racing.

The issue is cultural as well as medical. After the 2025 Tour de France Femmes, the union The Cyclists’ Alliance called on the UCI to mandate annual RED-S screenings and bone-density tests, arguing that the current system “does not sufficiently protect health” amid pressures on weight and performance. The federation responded by announcing, together with World Athletics, the creation of an e-learning module on RED-S and an imminent consultation with experts to update teams’ medical practices. Kigali, in short, will be the first major test of a technological piece—the GPS—that is part of a much broader puzzle, made up of race protocols, health protection, and a set of tools designed to turn safety from reaction into prevention.