Football in Greenland means community From icebergs to midnight sun matches

Imagine a football pitch surrounded by icebergs and snow-capped mountains. It’s June, yet the sun never sets. In Greenland, summer lasts barely three months, and for that entire time the ball is kicked day and night under the surreal glow of the midnight sun. Here, football is more than a sport: it is a social ritual, a collective mirror of an identity striving to assert itself on the global stage, despite a natural and political environment that often seems to push back. At these latitudes, football is the most beloved popular passion: more than 5,000 people—around 10% of the total population of just over 56,000—are registered players. A striking figure, considering that the outdoor competitive season runs from late May to mid-September, squeezed between ice, wind, and snow for over eight months of the year, and the near impossibility of maintaining natural grass pitches. As a result, futsal and synthetic or hybrid dirt-and-mud fields are widespread—surfaces that tell the story of a game built on adaptation and resilience, shaped in defiance of geography.

A federation outside the global system

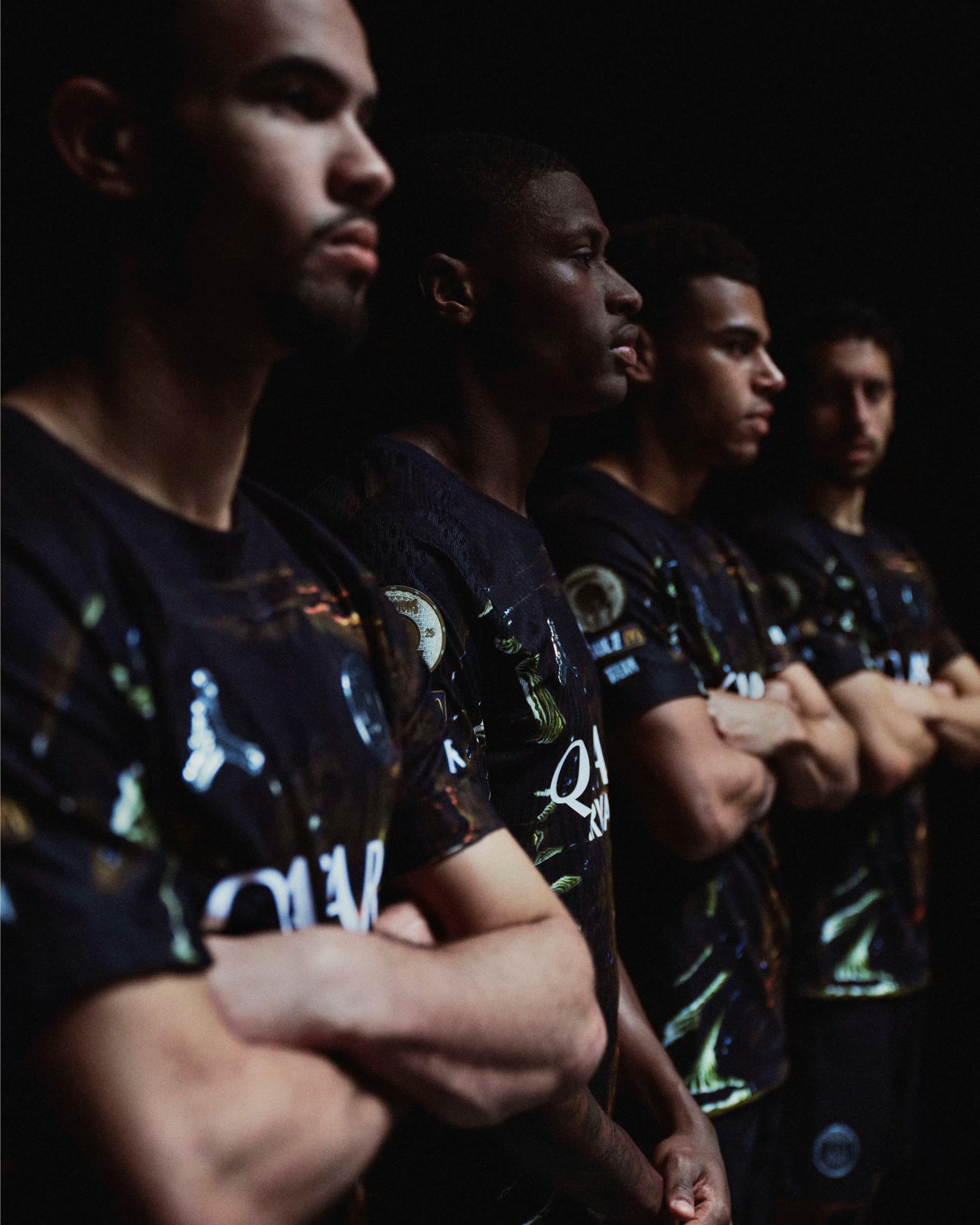

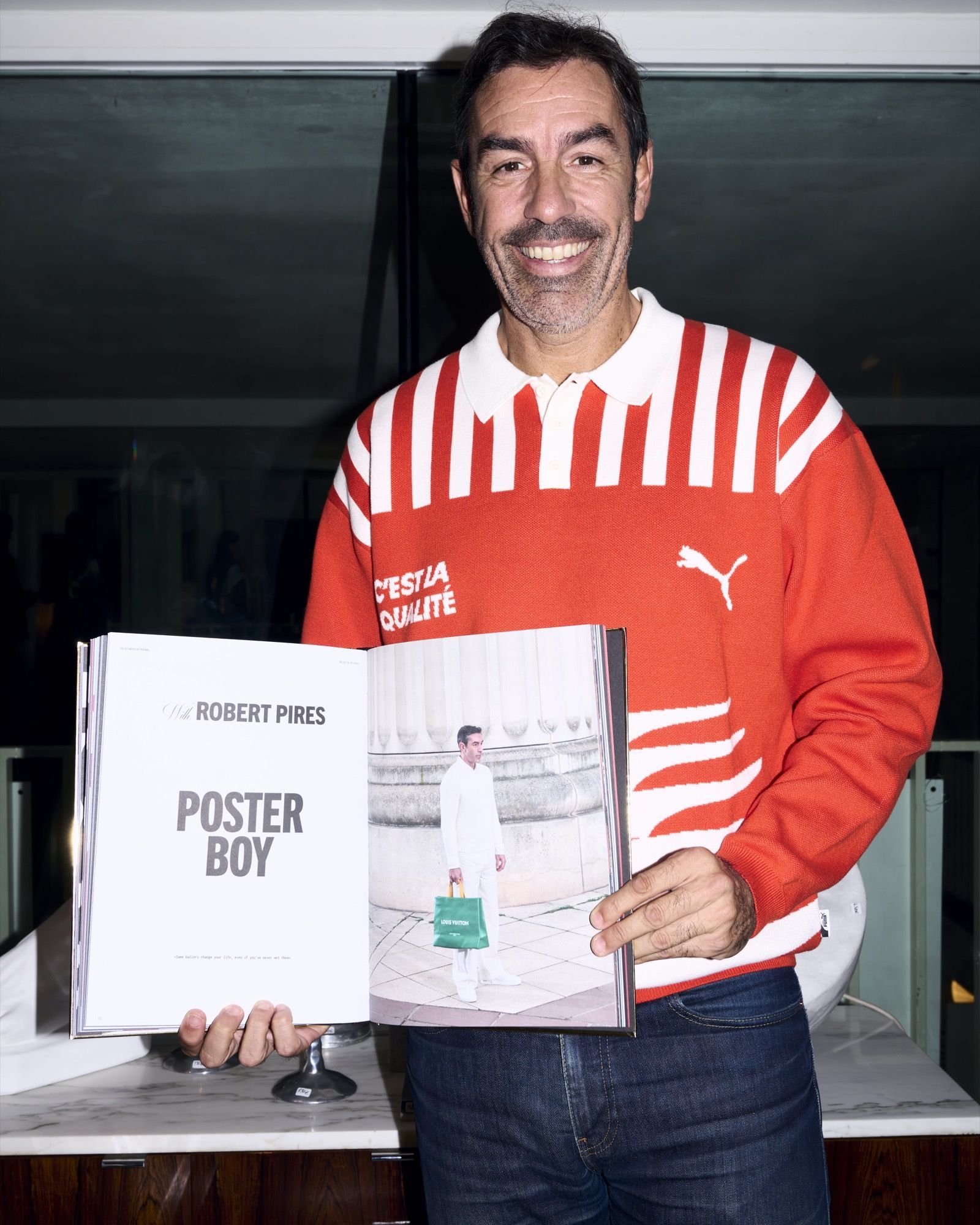

The KAK Kalaallit Arsaattartut Kattuffiat (Greenland’s Football Association), founded in 1971 in Nuuk, organizes the national championship and oversees the Greenlandic national team. The country is not affiliated with FIFA, UEFA, or CONCACAF, which as recently as June 2025 rejected Greenland’s latest membership application. This leaves the federation suspended between cultural pride and sporting frustration. The national team wears the colors of the flag—red and white—produced by Hummel, with jerseys that celebrate Inuit culture. These are not mere decorative elements: the tupilak, a spiritual protective figure, symbolizes strength and guidance; the tuukkaq represents courage; and the avittat patterns draw from traditional ornaments found on kamik boots and ceremonial garments. The kit is therefore conceived as a cultural project before it is a sporting one—a textile flag that tells the story of the land, its history, and the desire to be recognized worldwide. And as if that weren’t enough, the away shirt is dedicated to ice itself, paying tribute to the frozen landscape that unites and lives within every Greenlander.

The shortest league in the world

The spread of football on the island traces back to Danish colonization in the early 20th century. Since then, the ball has woven itself into local communities, becoming one of the primary tools of social connection among isolated settlements. Training sessions and matches serve as moments of gathering, storytelling, and shared identity. Today, the sport exists within a complex geopolitical context: Greenland has drawn the attention of U.S. President Donald Trump due to its strategic Arctic position and natural resources. Diplomatic tensions have fueled, among segments of the local public, political interpretations of the island’s lack of international football recognition. Yet Greenlandic football operates far from the billions of the global sports industry and the logic of super leagues. The national tournament, Angutit Inersimasut GM, features eight teams split into two groups, competing in an event compressed into just a few days—quite possibly the shortest football championship in the world.

@valentinpilate The most beautiful game, for every single soul on Earth. Like here, in Greenland at UUMMANNAQ.

original sound - liminal space songs

Here, passion makes up for a lack of infrastructure. B-67 Nuuk, with 15 titles, reigns as the queen of the ice. Its pitch—like those of other clubs—is nestled between rock and sea, with natural stone terraces serving as stands. Its technical sponsor is the Swedish brand Craft Sportswear, known for apparel designed for extreme climates and sustainability—a fitting choice for such a fragile yet spectacular territory. The city derby pits B-67 against Nuuk Idraetslag, founded in 1934, while other historic rivals include Kagssagssuk Maniitsoq, Inuit Timersoqatigiiffiat-79, G-44 Qeqertarsuaq, Nagdlunguaq-48, Kissaviarsuk-33, UB-83, and Upernavik FC. Behind these seemingly cryptic names lies a precise tradition inherited from the Danish sporting model. The letters often indicate the club’s original nature—for example, Boldklubben means “football club”—while the numbers usually refer to the year of foundation. Thus, B-67 stands for “Boldklubben af 1967,” and the same logic applies to many other teams on the island. A naming convention that has survived longer in Greenland than in continental football, becoming a distinctive marker of identity.

Football as community before spectacle

There is, however, one defining reality shared by all: to play, teams must travel by plane, speedboat, or sled for hundreds of kilometers. Every match is a logistical odyssey, every away trip an Arctic expedition. Within this remote universe, there is also a figure who embodies a possible dream: Jesper Grønkjær. Born in Nuuk in 1977, he is the most famous footballer of Greenlandic origin in the world. Raised within European football, he played for Ajax, Chelsea, Atlético Madrid, Stuttgart, and Copenhagen, earning 80 caps for Denmark across World Cups and European Championships. His Arctic roots remain a fascinating footnote in the story of globalized football—a symbolic bridge between the game on the ice and the sport’s grand international stage.

With stadiums that are not vast multifunctional arenas but small natural stages—worthy of a Nordic graphic novel or a post-apocalyptic film—in Greenland the pitch stretches toward the frozen horizon, and football becomes culture before business. It is a community before it is a spectacle. In a world dominated by global television networks and hyper-commercial storytelling, at the heart of the Arctic there exists a kind of football that does not seek attention for fashion, but for existence: under the midnight sun, beyond the snow, beyond the edges of the world. Regardless of who hopes to redraw them.