The 2026 World Cup is set to transform the landscape of football Cape Verde, Curaçao and all the fairy tales on the road to the FIFA World Cup

In recent days the 2026 FIFA World Cup has taken shape in increasingly concrete terms. The next edition, which will be co-hosted by the United States, Canada and Mexico, and in which the new XXL format introduced by FIFA will debut: forty-two national teams have now qualified, with the last six spots to be decided in the March play-offs. And while Italy is once again embroiled in the playoff scramble, in other parts of the world teams with much less tradition have secured their places: in some cases for their historic first time, such as Curaçao and Cape Verde; in others after decades of absence, as in the case of Haiti. Yes, they are names that even sound odd to hear associated with a FIFA World Cup, and they confirm how the geography and the qualification criteria for the event have been revolutionized.

The two most thrilling finishes in UEFA European Qualifiers rewarded Scotland and Ireland, who earned, respectively, a spot in the tournament finals and a place in the play-offs at the last breath (and beyond). The former thanks to a victory over Denmark inspired by the Neapolitan Scott McTominay, author of a memorable overhead-kick goal; the latter after two wins against Portugal and Hungary, driven by the new national hero Troy Parrott. In the CAF area (Africa) the latest surprise was instead produced by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which beat Cameroon first and then Nigeria, amid voodoo rituals on the bench and a dream that now passes through the Mexican play-offs in March. From the CONCACAF zone (Central America and the Caribbean) Suriname and Jamaica have also entered this do-or-die race, chasing their first and second-ever World Cups respectively, while on the AFC (Asia) perimeter two newcomers are close to a World Cup debut: Uzbekistan and Jordan. But the most extraordinary feats were signed by two national teams that set new, unthinkable records for geographic and demographic size: Cape Verde and Curaçao.

Cape Verde: more than a former Portuguese colony

To grasp the significance of what Cape Verde has achieved, simply consult a map and consider a few key figures. It is an archipelago of ten small islands in the middle of the Atlantic with a population of just over half a million, as well as a large diaspora spread across Europe, Africa, and the Americas. It is the second-smallest country ever to qualify for a World Cup, after Iceland in 2018 — although this record was broken a few weeks later by the even more impressive achievement of Curaçao. Cape Verde's qualification was secured with a decisive victory against eSwatini, but this success was built upon in the earlier group matches. At the Estádio Nacional in Praia — a stark setting among volcanic hills — about 2% of the entire national population (15,000 spectators) witnessed the story of the Tiburones Azules, the Blue Sharks. The decisive match was played there, ending 1–0 against Cameroon, the African nation with the most World Cup appearances. The winning goal was scored by Rocha Livramento, a forward and former Verona player who now plays for Casa Pia in the Portuguese league.

Cape Verde has always shared a close relationship with its former motherland for historical, cultural, linguistic and footballing reasons. From the Cape Verdean origins of Eusébio, a Portuguese football legend, to the new era of naturalisations that have contributed to the growth of the movement, we can see this relationship in action. Today, however, the national team tells another story, also through the kits made by Tempo Sport, which carry onto the field the identity and geography of the small archipelago: the blue of the flag, the ten star-islands repeated across the uniforms, a country that draws its post-colonial identity beyond Portuguese green and red. In 2024 Cape Verde celebrated fifty years of independence, and the World Cup qualification given to its citizens, including those who live far away, is the most powerful way to turn a name born from a geographic mistake — when Portuguese explorers thought they had landed at Cap-Vert in Senegal — into a recognizable presence in the global football imagination. It is the culmination of football growth anticipated by quarter-final appearances at the Africa Cup of Nations in 2013 and 2023, and comes just over twelve months after the nation's first Olympic medal won by a Cape Verdean athlete (David de Pina, Paris 2024).

Curaçao: the Caribbean miracle

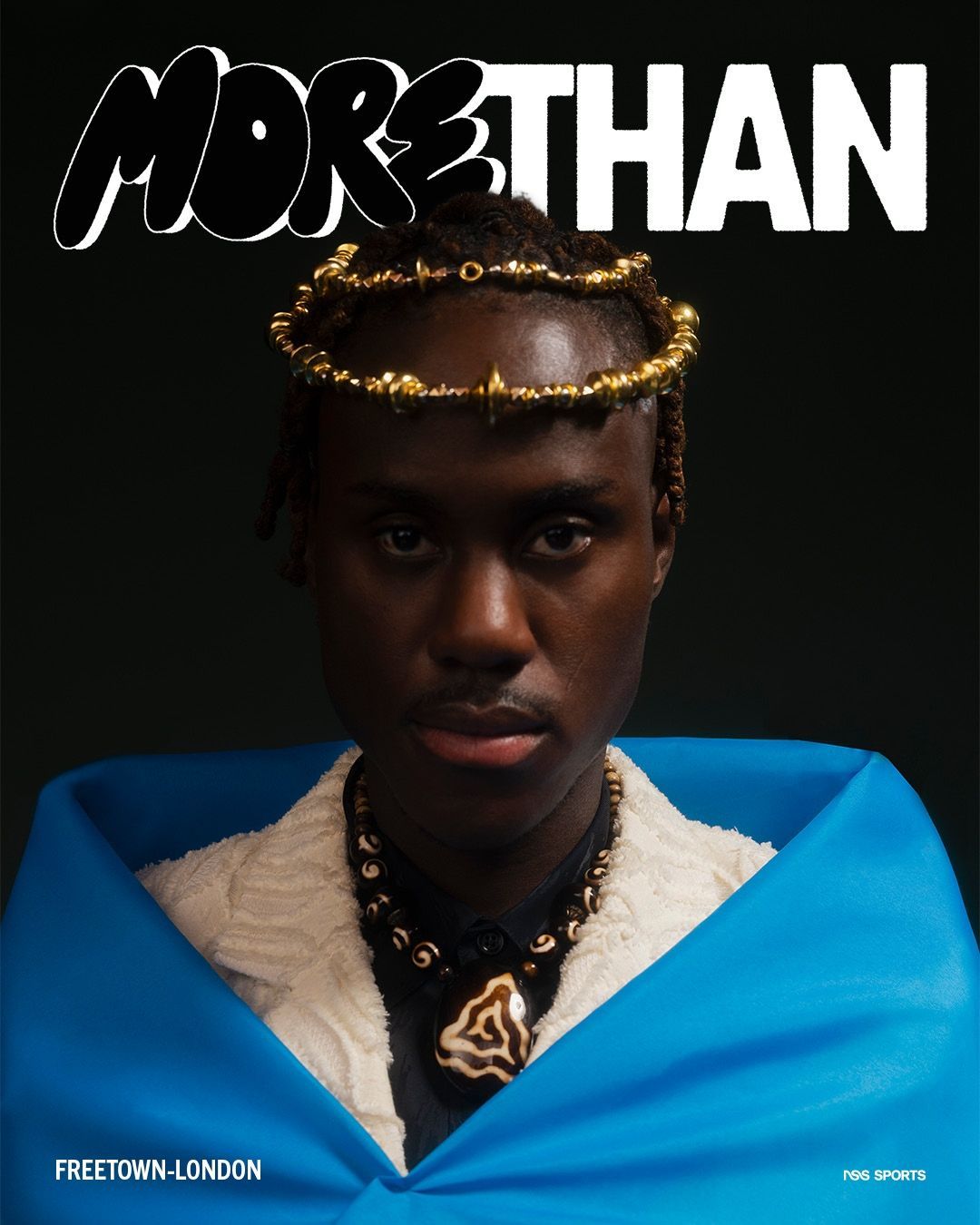

Meanwhile, just as we were still marvelling at Cape Verde's achievement, another tiny dot on the map broke the records again. Curaçao is an island located 60 kilometres from Venezuela. It covers just 444 square kilometres and is inhabited by fewer than 160,000 people. It is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and has its own government and parliament. The official languages are Dutch and a Creole language. Until a few days ago, many people mainly associated it with a liqueur and postcard-perfect Caribbean scenery. Today, however, it is the smallest and least populous nation ever to qualify for the final phase of a World Cup.

The path to the 2026 World Cup was clear-cut: seven wins and three draws in the group, 24 points that earned first place ahead of Jamaica. It is the brightest point of a journey that started a long time ago, which saw the team rise from 150th to 80th in the FIFA rankings in a decade. A result until recently unthinkable, achieved also thanks to the guidance of Dick Advocaat, a 78-year-old coach who landed in Willemstad at the start of 2024 after stints across the football map with national teams like the Netherlands, Russia, Iraq, the UAE and South Korea. His role was more of a connector than just a coach, having convinced a good list of players raised in the Netherlands but eligible for Curaçao to choose the island. And so a national team that draws from a tiny population found itself with a core accustomed to elite football, with ties reaching as far as the Serie A (Livano Comenencia, raised in Juve Next Gen).

It is a result "that completes a project started in 2004 and in which we never stopped believing", says Gilbert Martina, head of the local football federation. "After 21 years, we did it. And it is a wonderful feeling, a gift for all Curaçaoans in every corner of the world. We are a small country, but with people big in soul and heart". Curaçao will not be an isolated exception, but one of three Caribbean representatives at the World Cup: the most extreme point of a movement that has exploited FIFA's expansion of berths to open new opportunities. Stories that are impossible not to find fascinating as long as we look at them from afar, like exotic tales, but the narrative breaks down when they are put in relation to the big European teams left out — often bringing back the eternal accusation of a denatured World Cup.

Reactions and Eurocentrism

While Gilbert Martina's statement that "we have already won our World Cup" captured the historic importance of Curaçao's qualification, it has drawn criticism from Europe. This is because FIFA has chosen to reduce the number of European teams at the World Cup. This is a decision that is, of course, above all commercial and political, but inclusive nonetheless, opening the doors to federations that had previously been systematically excluded from the biggest tournament in global football. These sporting feats, both large and small, will make the 2026 FIFA World Cup the most diverse and least Eurocentric ever. In recent weeks, they have brought stories to the public that go well beyond sport, revealing distant and often lesser-known identities. There are plenty of reasons to welcome the vindication of those who have always lived on the fringes of the empire with curiosity and enthusiasm.

From a purely technical point of view, one can say that the next European Championships (United Kingdom and Ireland 2028) will be of higher quality compared to the upcoming World Cup. It may seem strange and counterintuitive, but it's only a matter of perspective. Who said, after all, that FIFA must organize the highest-quality tournament with the World Cup, and not the most extensive and representative one? As in other contexts, footballing and otherwise, every attack on Eurocentrism is perceived as a way to distort the product, but it is a limited viewpoint that does not ignore a trajectory that many international tournaments share. The foundation of the expansion — namely sports colonialism and the perpetual pursuit of revenue — can be exciting to some, and that's normal. Just as recent choices about host venues need no added commentary beyond the already eloquent list: 2018 to Putin's Russia, next year to Trump's United States (already the White House occupant at the time of the award), concessions to Gulf petro-states with Qatar 2022 and Saudi Arabia 2034. But the discussion about FIFA's widening of borders and the decentralization of European football has various nuances.

Despite the delicate political context, the sponsorship of the Infantino-Trump bromance and those who unyieldingly defend the privilege of UEFA national teams, the expanded format and the inclusion of more national teams from CAF, CONCACAF and AFC will make the 2026 World Cup the most 'colourful' edition ever. It will be beautiful and unique precisely because of this, as well as being fairer, more inclusive and more democratic. After all, we are living in a historical moment that cries out for open doors, torn-down barriers, distant cultures drawing closer and evolving traditions — and if the cost within FIFA is the exclusion of a handful of big teams from the old continent from the World Cup, and perhaps some much more lopsided group matches, it is a price that is absolutely acceptable.