Crystal Palace forced UEFA to change its rules Multi-club ownerships are all around us

In recent months Crystal Palace had its spot in the Europa League for the 2025/26 season —earned by winning the FA Cup— revoked by UEFA. The club was relegated to the third continental competition, the Conference League. The reason? A conflict of interest that the club failed to identify and resolve within the deadlines set by the rules on multi-club ownership (MCO). The issue concerned the link with Olympique Lyonnais, since ownership of the French club was attributable to John Textor, an American entrepreneur and founder of Eagle Football Holdings, who in recent years also acquired stakes in Botafogo (Brazil) and RWD Molenbeek (Belgium) in addition to Crystal Palace.

After a summer of intense controversy, the Crystal Palace case —which president Steve Parish called "one of the greatest injustices ever to happen in European football"— has moved from newspaper headlines to UEFA's agenda, becoming a hot political issue. Multi-club ownerships are an increasingly common phenomenon, in Europe and beyond, and Palace was not the only recent victim of these rules; there are also Drogheda United (Ireland) and Dunajská Streda (Slovakia), which for similar reasons had to cede their place in the Conference League to Silkeborg IF (Denmark) and ETO Gyor (Hungary). A multiplying number of warning signs that cannot be ignored in Nyon.

Tunnel is the weekly nss sports newsletter that collects the best of sportainment. Click here to subscribe.

According to a recent report by The Guardian, the debate has laid the groundwork for a regulatory turning point regarding the timing and the tools used to handle such situations. "Either you accept multi-ownerships", said —with sound arguments— Steve Parish, Crystal Palace's chairman, "or you ban them outright. But UEFA is at a crossroads and has to reflect, and then find a way out, because this situation makes no sense."

Crystal Palace vs UEFA

The sequence began last May with Palace's surprising FA Cup victory, their first historic national title. With that win came qualification for the 2025/26 Europa League, which would have been a first for the Londoners. Meanwhile, Lyon —at the time under Eagle Football's control— also secured the same European spot, creating the conditions for intervention by the CFCB, UEFA's club financial control body. Federation rules prohibit two entities under "decisive influence" of the same person from competing in the same competitions, unless that governing body approves a blind trust on one of the assets.

The deadline to report a potential overlap and thus obtain CFCB clearance —usually by restructuring the ownership of one of the two clubs— is currently set at March 1st. And here lies the problem: the British club missed the deadline, understandably since in February, with the FA Cup still at the round of 32 stage, few would have predicted winning the tournament. So once Palace secured the spot, the CFCB reacted immediately by sanctioning the club, downgrading it to the Conference League and leaving Lyon with the Europa League berth. UEFA hierarchy gives priority in this sense to league position over a national cup title, and thus Selhurst Park fans had to digest the sad outcome, which was confirmed even after an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Lausanne.

The club appealed the decision and argued that its situation was different from many other MCO cases, even prior to the summer corporate reorganization. It was demonstrated that John Textor did not exercise "decisive control" over the club, especially regarding sporting decisions, and that his share had in the meantime been acquired by a new shareholder, Woody Johnson. But for the CAS none of that mattered: what counts is the snapshot at the date of assessment, i.e. March 1st, with no room for maneuver —neither for clubs nor for the federation— in subsequent months. "We proved beyond reasonable doubt that John had no decisive influence over anything regarding the club,” continues Steve Parish, “yet they still reached this decision, which seems incongruous. The rule will change; nobody wants to keep following this incomprehensible madness."

The turning point

As the rule stands today, it evidently clashes with the European football calendar and with the logic of MCOs which, as Parish has repeated for months, UEFA has accommodated within its perimeter for some time now, albeit with rather restrictive rules. In Palace's specific case the asymmetry between practice —an increasingly networked system of this kind— and theory —namely the rules on conflicts of interest— produced an estimated economic loss of €25 million. Added to that is the sporting damage in meritocratic terms, at the expense of the human personnel inside and around the club.

Palace lost the battle, but brought the issue to the attention of a wide audience, and may have changed the course of a much deeper conflict. In Nyon, as revealed by Matt Hughes for The Guardian, they are indeed considering a new dual deadline: a timeline that would keep clubs' obligation to report potential issues by March 1, but extend until June the window to resolve them. A shift that would allow clubs to wait for the verdicts delivered on the pitch without missing the dates of the draws for the European qualifying rounds. A correction that does not absolve late reporting —those who fail to notify by March would remain in breach— but that opens the possibility of dealing with conflicts ex-post when the violation becomes concrete.

Such a measure could be accompanied by some revisions to the meaning of "decisive influence", which in Palace's case was a central point of contention. The issue will resurface and is inevitable in a context increasingly populated by multi-ownership networks. Entities that are ever more varied and complex, and not necessarily central to a club's day-to-day sporting life.

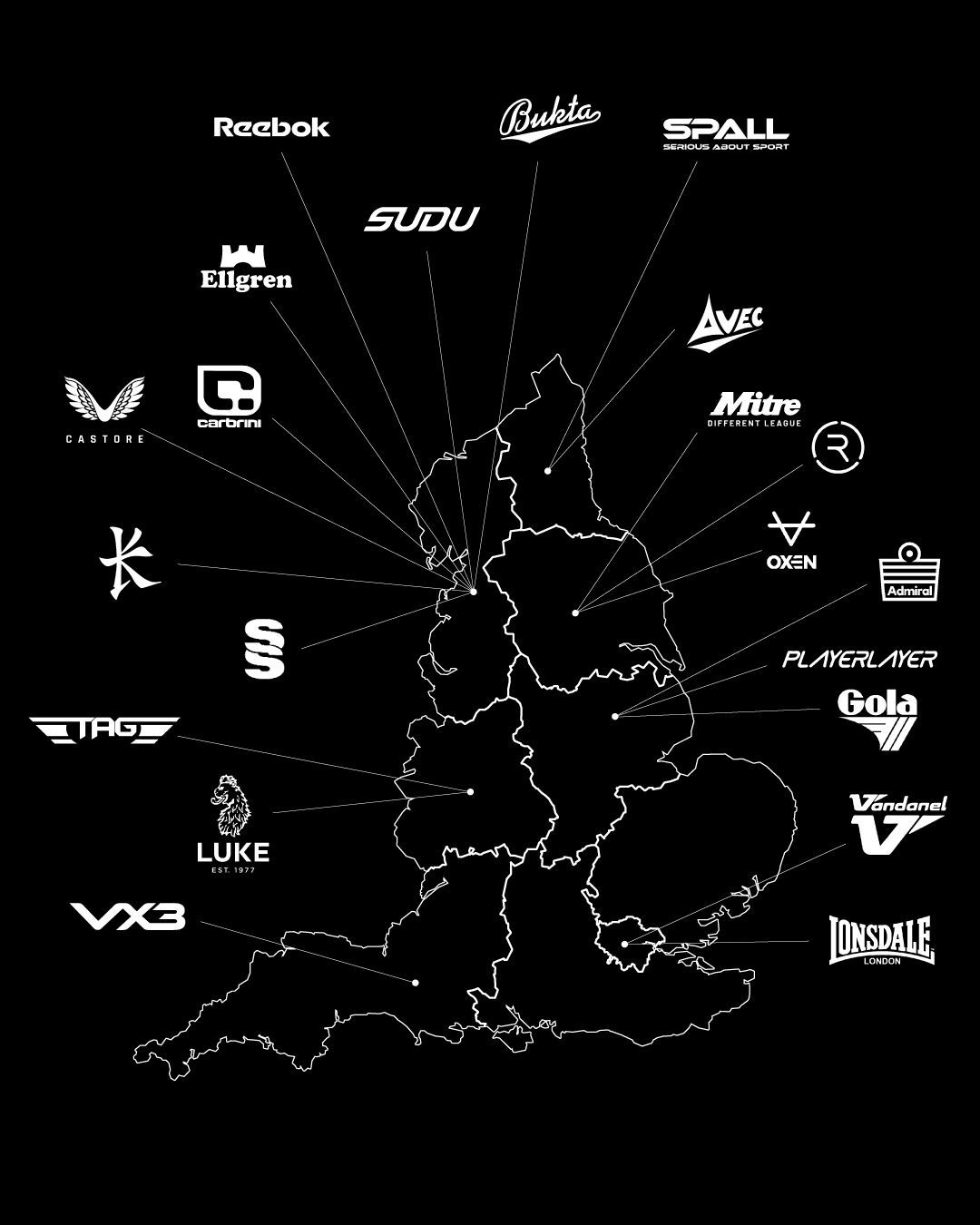

Multi-ownership in Europe

Multi-club ownerships are no longer an exception in the Europe. According to a 2024 UEFA financial report, the number of affected teams —over 250— more than doubled in five years, and the phenomenon is set to expand further. At the center of the mega-networks is the City Football Group, linked to Manchester City and uniting a constellation across Europe including Spain (Girona), Italy (Palermo), Belgium (Lommel) and France (Troyes); but not only Europe —also the United States (New York), Japan (Yokohama), Australia (Melbourne) and Uruguay (Montevideo), among others. The project integrates scouting, development and the movement of talent across multiple leagues, with the Manchester–Girona axis representing an important regulatory node in 2024, when both clubs were admitted to UEFA competitions following the transfer of shares to external investors.

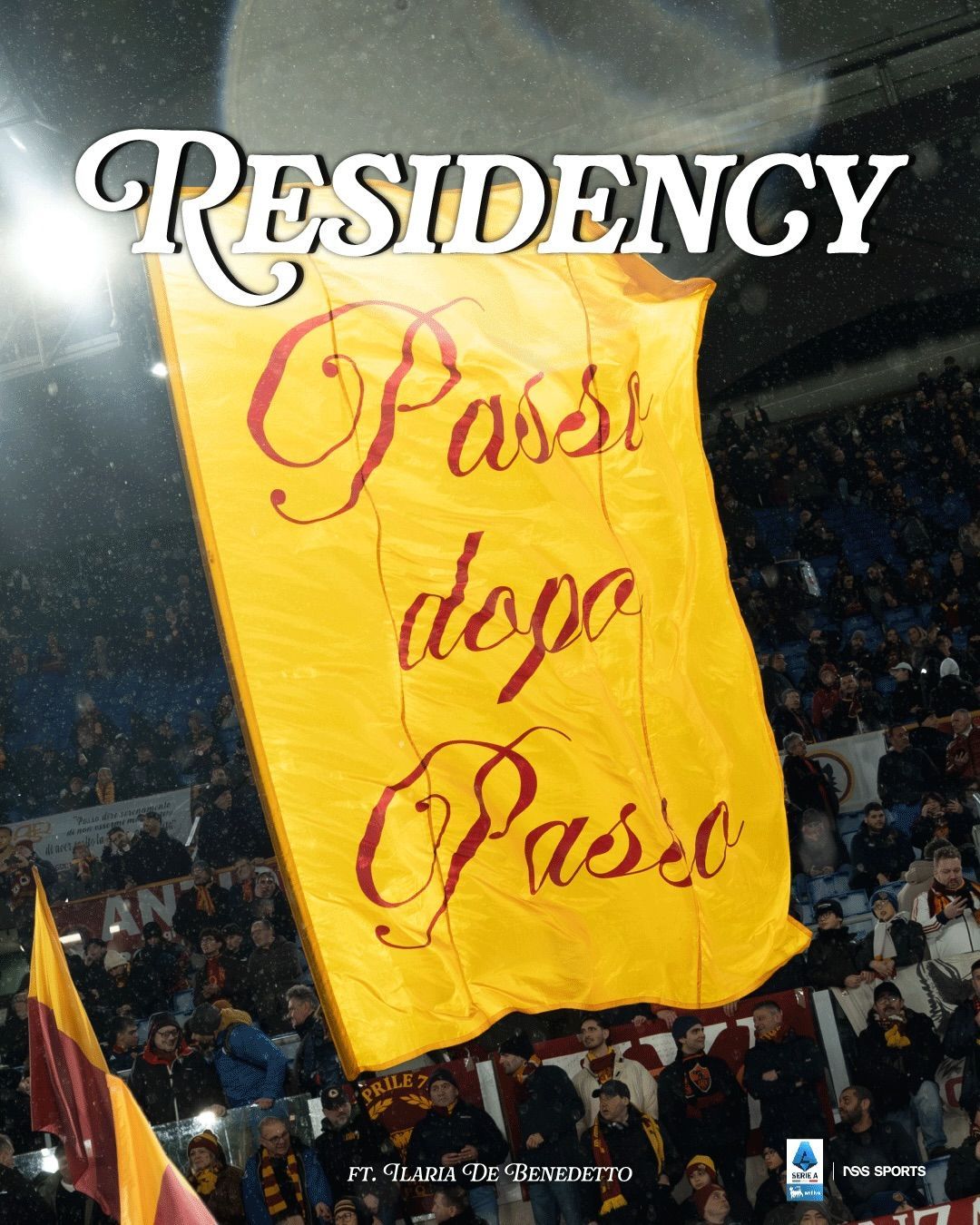

The other major ecosystem is Red Bull, centered on Salzburg and Leipzig with other satellite clubs around them, continental and beyond. The group in 2017 reached an agreement with UEFA financial bodies for the coexistence of the clubs, always after governance revisions and guarantees on the group's influence. There are many smaller cases, each with its own logic and dynamics: INEOS (Manchester United and Nice), RedBird (AC Milan and Toulouse), V Sports (Aston Villa and Vitoria de Guimarães), BlueCo (Chelsea and Strasbourg), 777 Partners (which has also been involved in Italy with Genoa), Friedkin (Roma, Cannes, Everton), Pozzo (Udinese and Watford). And, as mentioned, John Textor's Eagle Football.

In Italy, to close the loop, the matter is governed by art. 16-bis NOIF, which bans the control of multiple professional clubs domestically and aims to eliminate multi-ownerships at home by 2028. By that deadline the few remaining multi-ownership groups, in order to protect the integrity of the sport, will have to dissolve permanently. The case study is Claudio Lotito, who simultaneously headed Lazio and Salernitana. When the latter were promoted to Serie A in 2021, the FIGC allowed an independent trust, provided the club was sold within six months or faced exclusion. A variant of the blind trust also used by UEFA, and a scenario that could recur if Napoli and Bari, both linked to Aurelio De Laurentiis, were to find themselves in the same division. The latest two cases show a phenomenon that domestically is disappearing —rightly— in Italy as abroad. But internationally it still has to find a fair, peaceful and shared dimension.